By Charles Skorina, Managing Partner at Charles A. Skorina & Company.

I worried about so many things during my life, but the really tough hits I never saw coming. — Anonymous

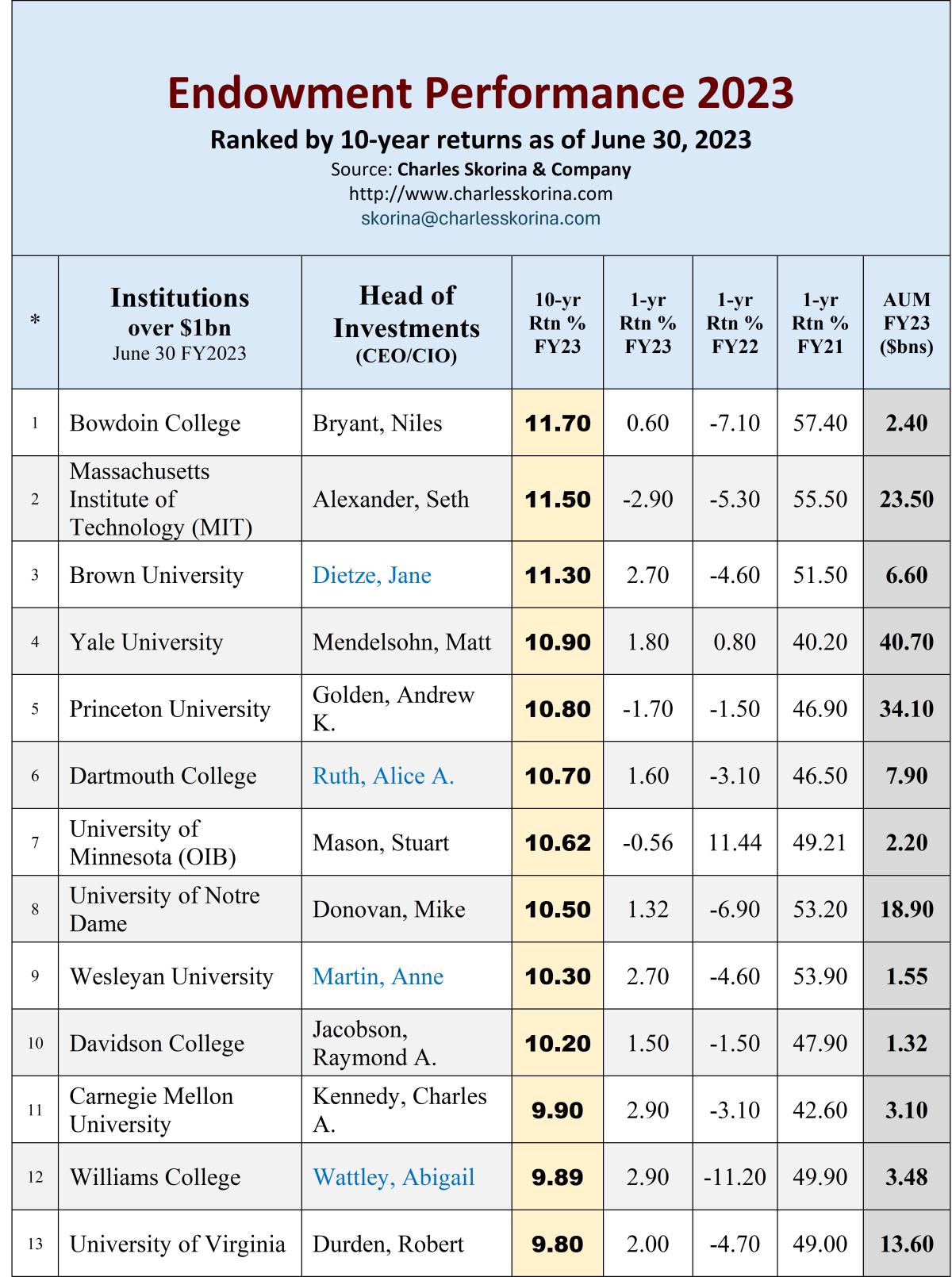

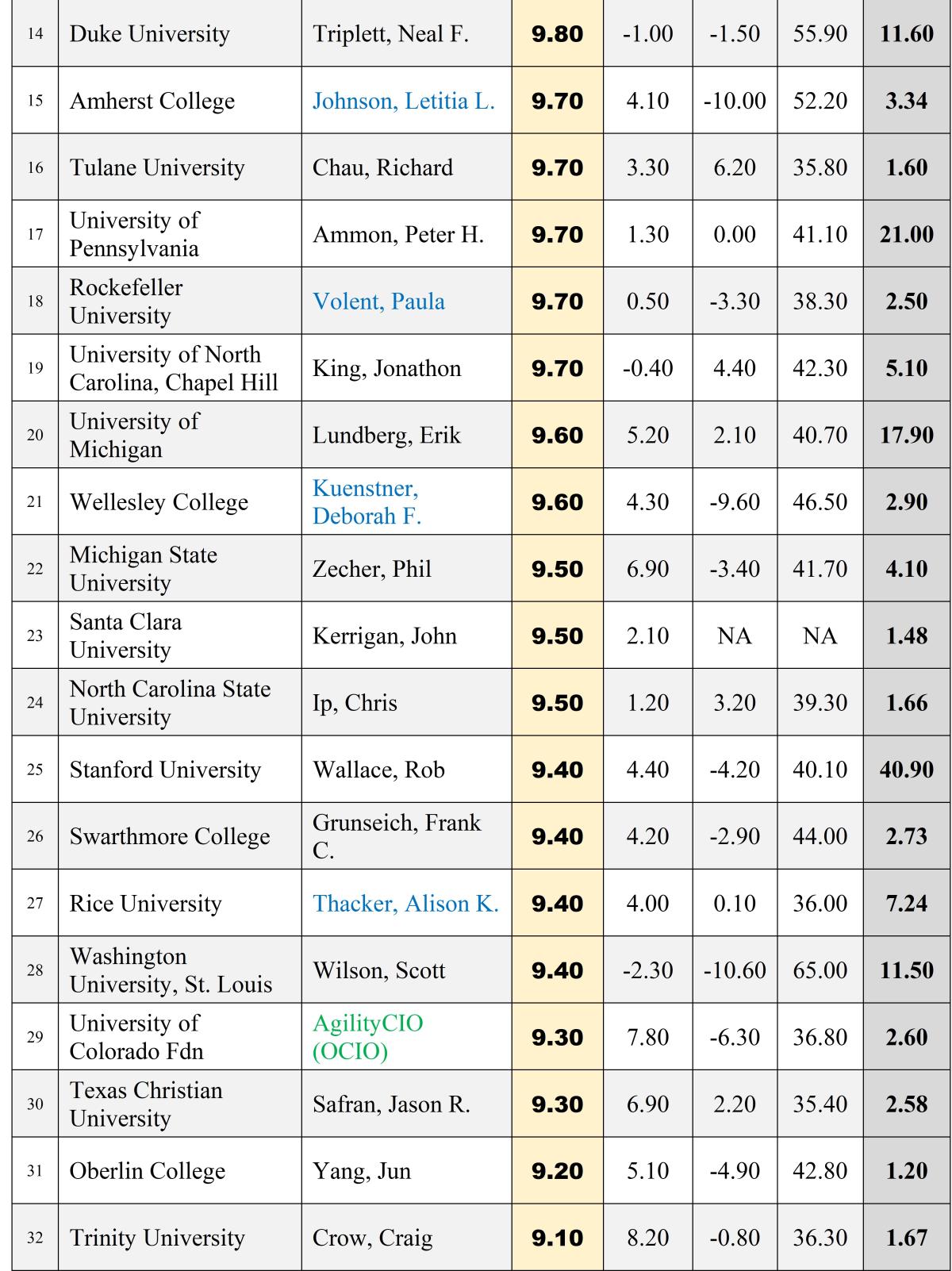

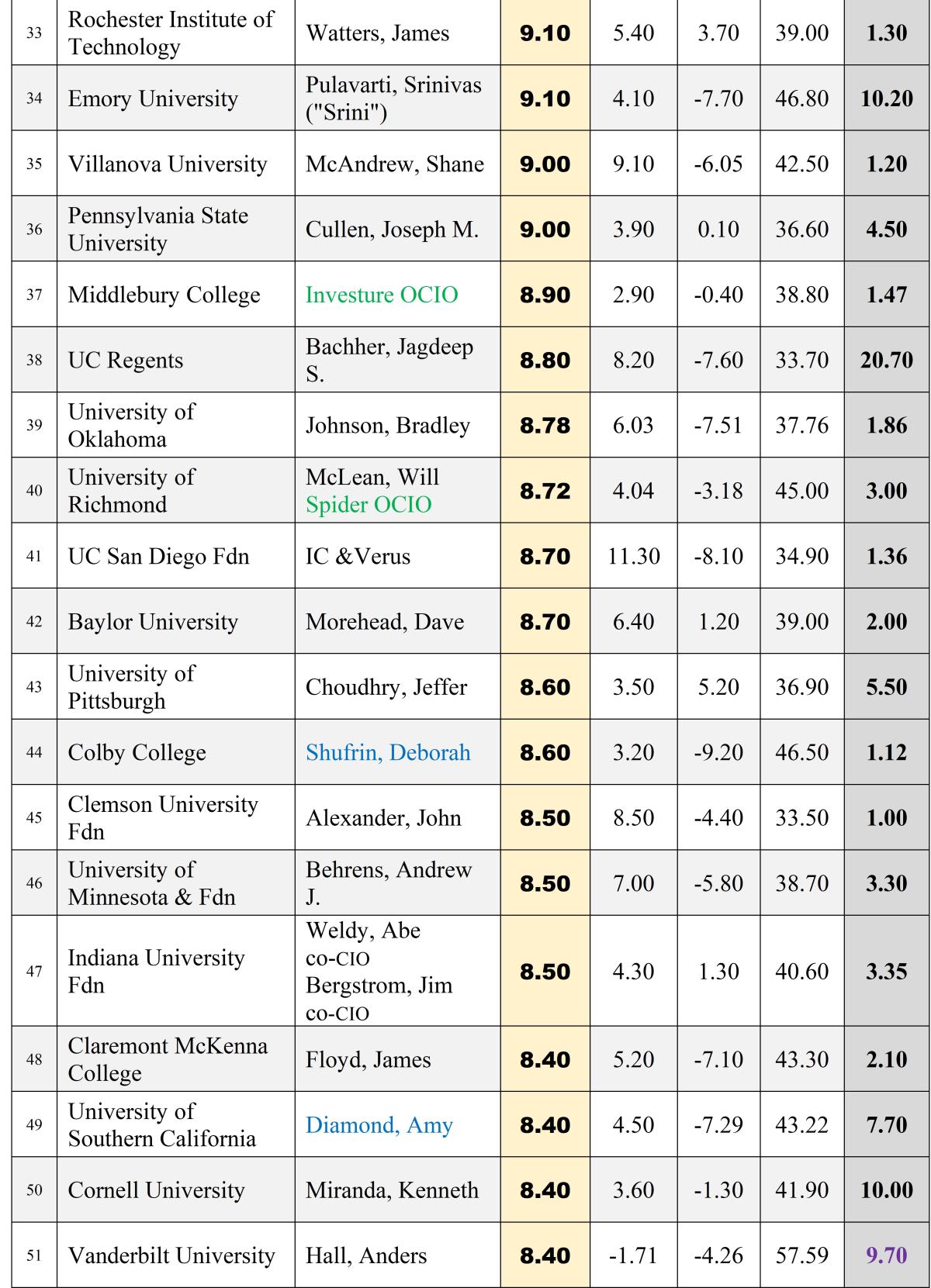

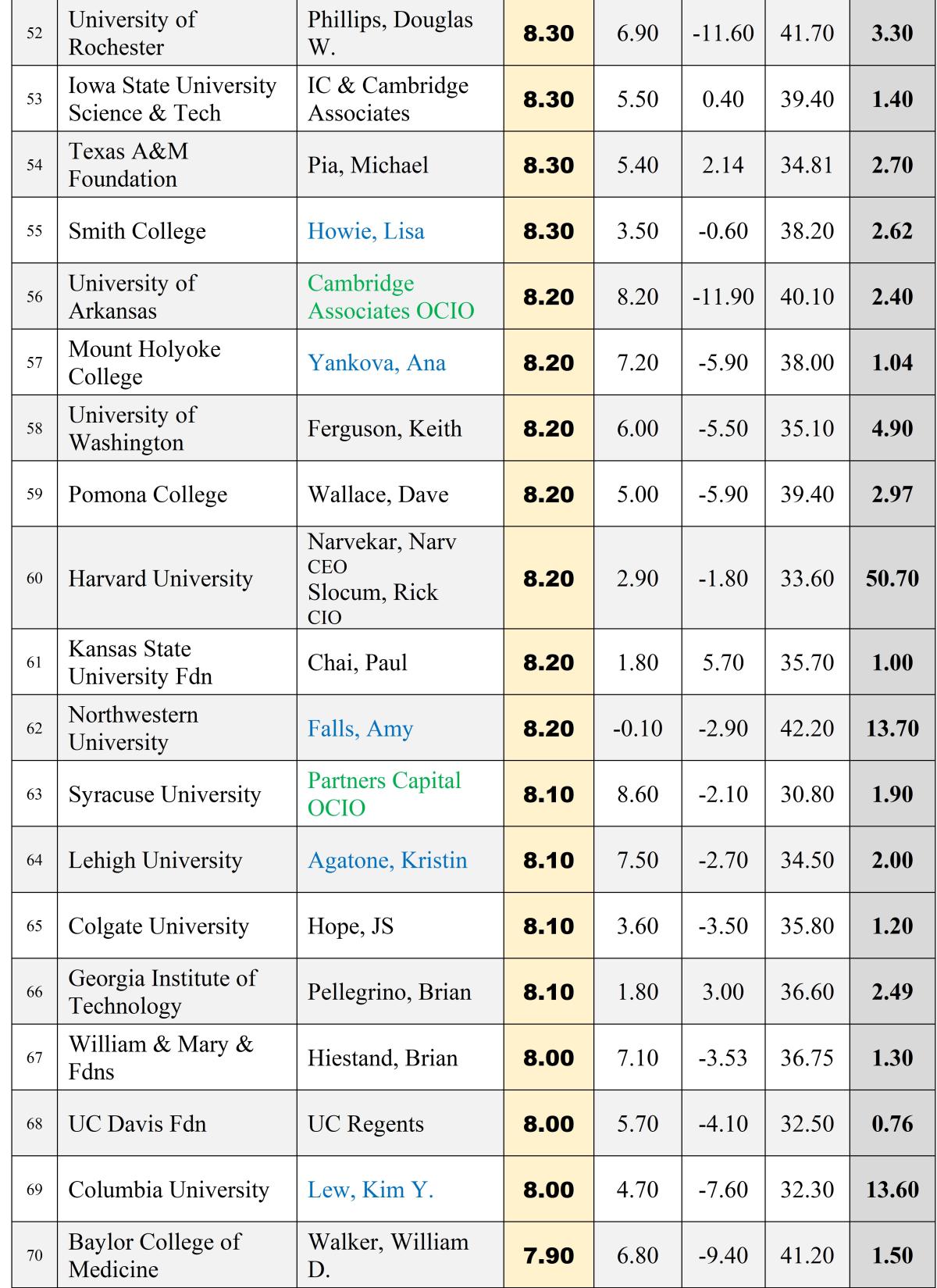

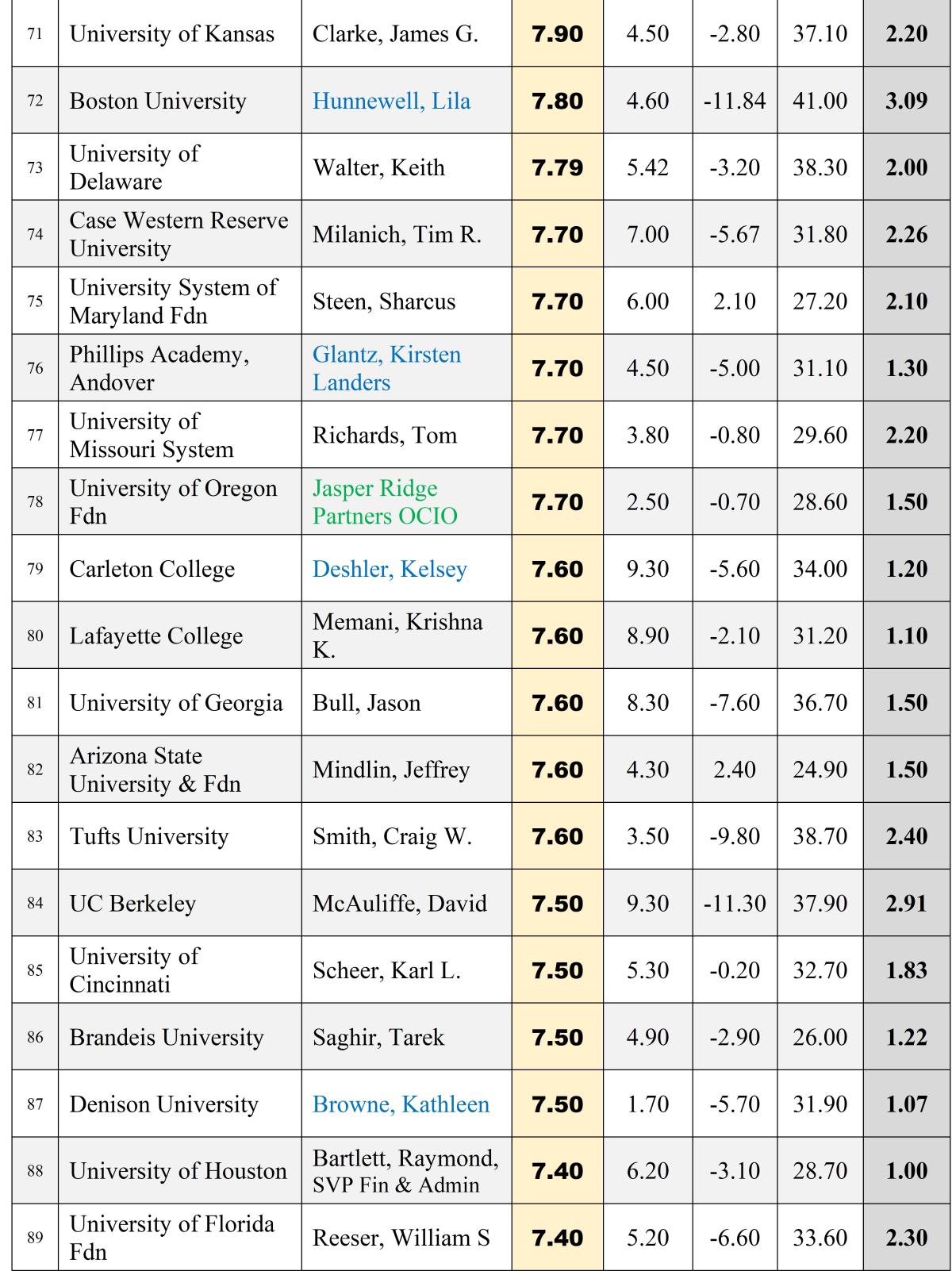

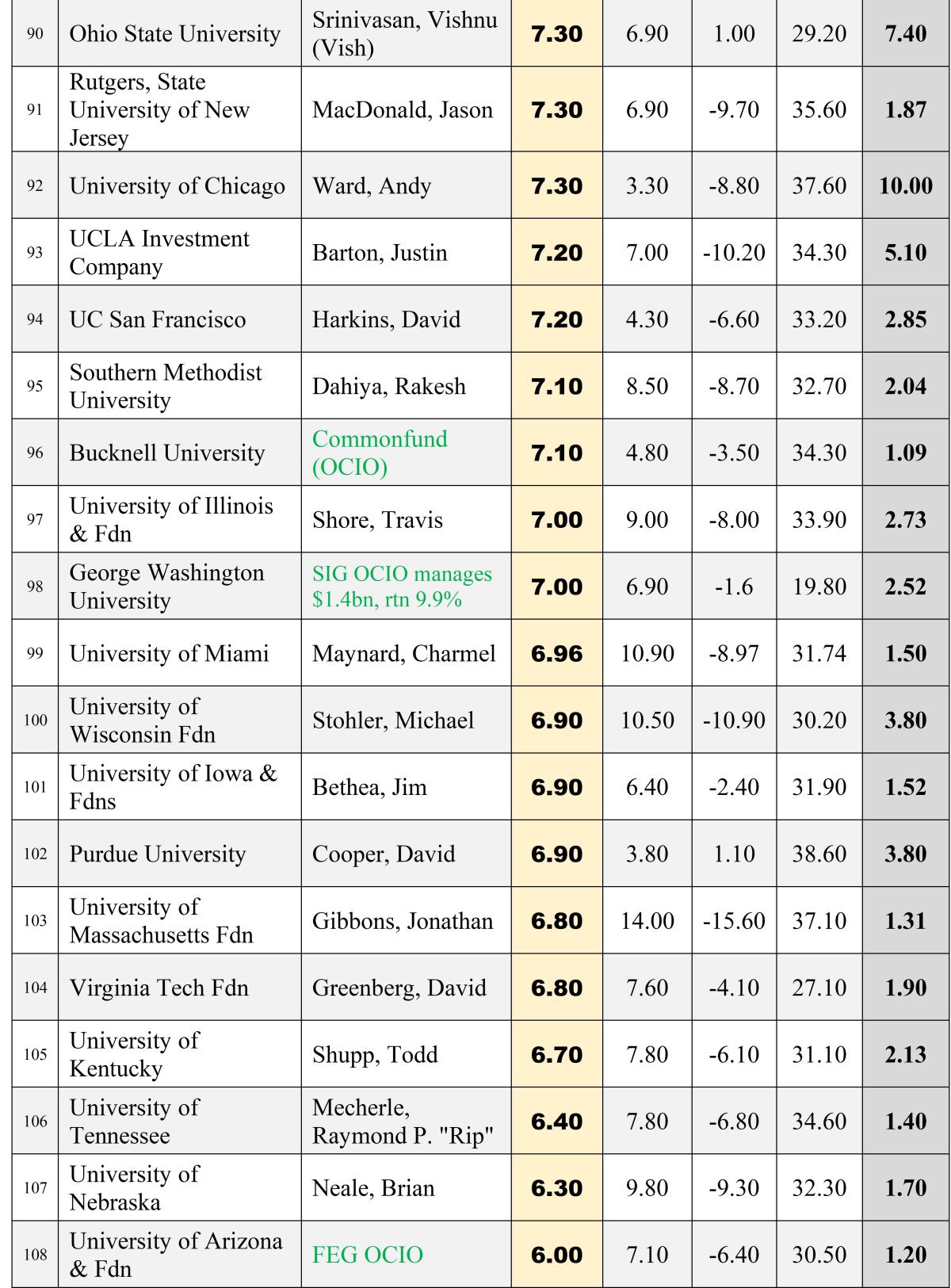

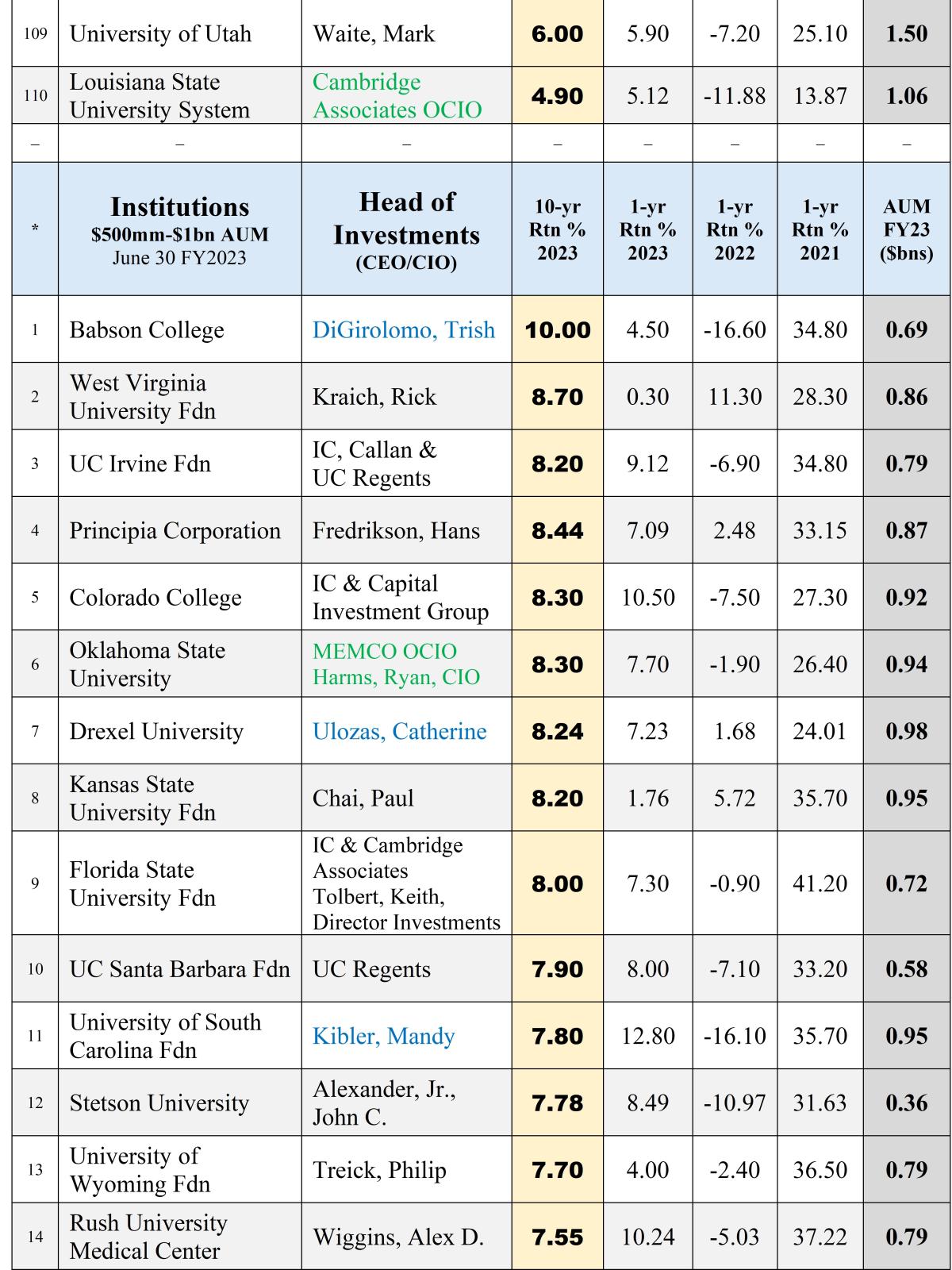

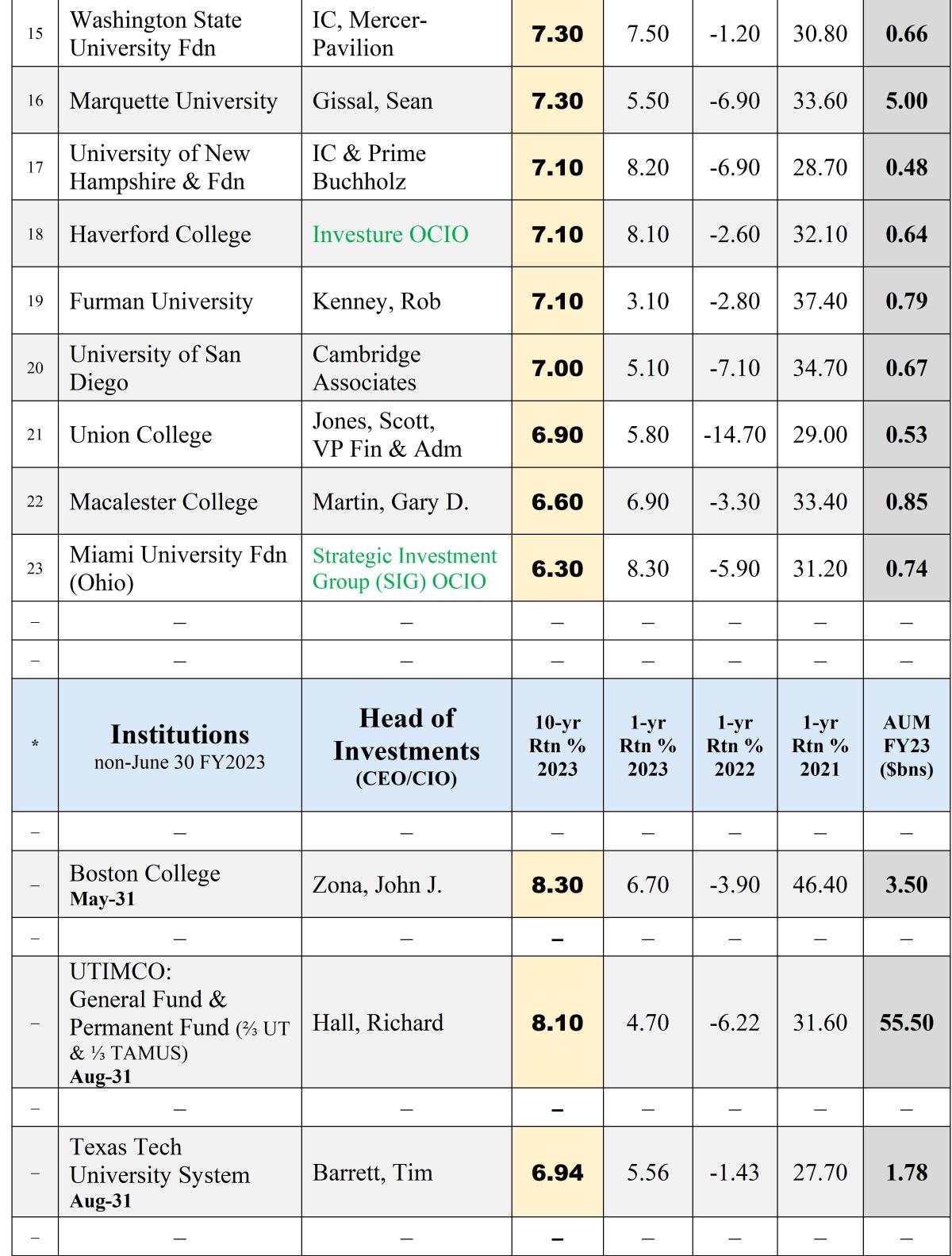

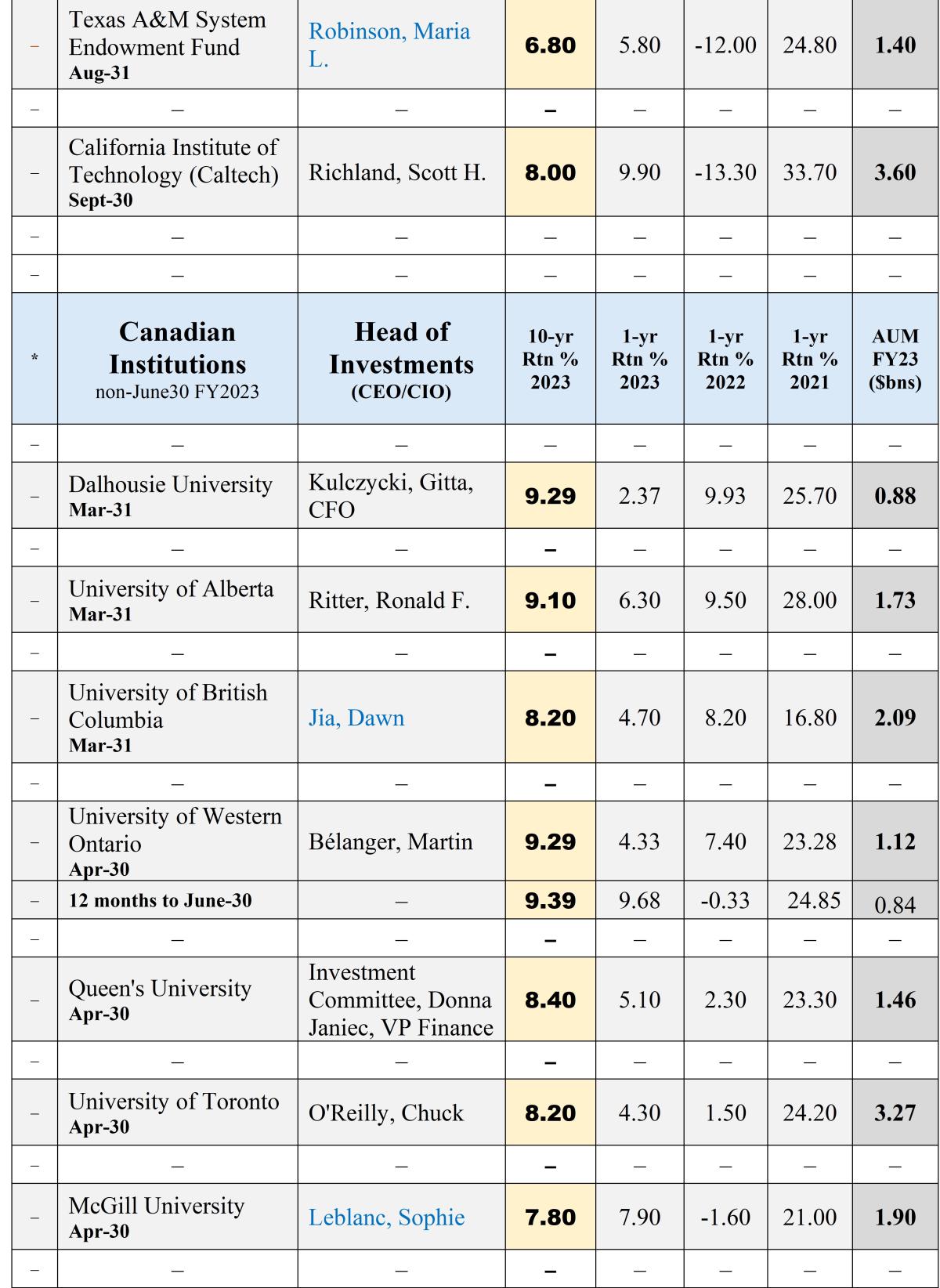

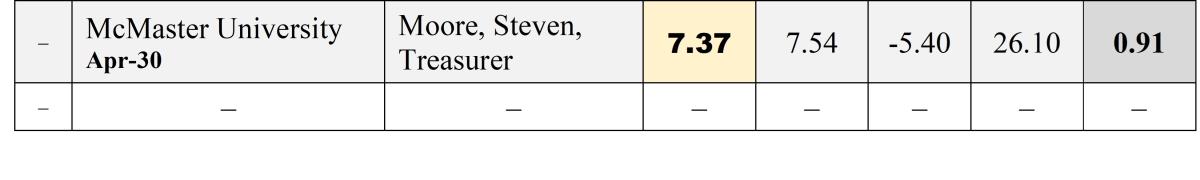

Our 2023 endowment performance report features ten-year investment returns for one hundred thirty-eight US and eight Canadian institutions, the latest available. In addition, we include one-year returns for 2023, 2022, 2021 along with AUM, as of their respective fiscal year-ends.

NACUBO and Commonfund released their annual endowment study two weeks ago chock full of facts and figures. Chief among them, the 688 participating U.S. college and university endowments and affiliated foundations returned 7.7 percent, net of fees, for fiscal 2023. Trailing 10-year returns averaged 7.2 percent.

NACUBO noted that “Historically, institutions with larger endowments often have secured better one-year investment results than those with relatively smaller endowments. The reverse occurred in FY23, owing to smaller institutions’ substantially larger allocations to publicly traded securities.”

All this is nice to know, but in our line of work, acquiring talent and capabilities for institutional and family office clients, we like hard data on the individuals who drive the investment decisions. Returns may be historical, but they are useful cues to an investor’s process and discipline.

As it turns out, of the 688 institutions in the NACUBO study, including 138 endowments over one billion AUM and 77 between $500 million and a billion, only about a third have an internal chief investment officer or designated investment head, mostly those in the above mentioned half a billion and up categories. These are the ones that catch our eye. The rest use OCIOs, investment committees and consultants, RIAs, brokers, and well-meaning volunteers.

The lay of the land

Institutional investors had a lot on their minds the last few years: Covid and a market crash in 2020, meme stocks and valuation- frenzy in 2021, war and rates in 2022, and bank busts in 2023. But other than the specter of rate increases, no one saw these disruptive outliers coming.

And yet, the best investors somehow find a way to outperform. After years of recruiting investment talent, we’ve observed that top performers tend to stay on top, despite the occasional speed bumps.

Cambridge Associates concurs. In a 2022 paper on investment advice for the entrepreneurial mindset, CA studied equity portfolio managers over a twenty-year span and found that, “On average, “successful” managers underperformed about one quarter of the time over any rolling three- and five-year periods.”

Unfortunately, it’s hard to find good data on nonprofit CIOs with twenty years or more of tenure, but ten years is doable. Hence our emphasis on ten-year performance.

We also list the current endowment CIO or designated head of investments, although often performance was baked in by the prior CIO.

Paula Volent for example, now at Rockefeller University, was for twenty years the CIO at Bowdoin College and her fingerprints linger on Bowdoin’s latest 11.7% ten-year return, topping our charts yet again.

Where are the women?

Speaking of the women, we wrote in 2021 about the long hard road for women in finance. Not much has changed since, at least among the ranks of chief investment officers. We can find only 24 female investment heads or 17.4% among the 138 schools on NACUBO’s over one billion AUM list. In our report, we list 19 women among the 110 endowments over one billion, despite consistent top-tier performance. A conundrum.

Aims and Objectives

We consider a ten-year span to be a rigorous and revealing measure of the strength of an institution’s long-term investment abilities, but we remind our readers that there’s much more to the story.

Board members and administrators set the parameters for investment execution, and they are the ones to judge whether their goals are met.

Every school has its own endowment payout rate and tolerance for risk and that’s what CIOs aim for. Some schools rely heavily on income, others place more weight on growing the principal.

Issues and challenges

For recruiters and the inquisitive, however, there are challenges. Take, for example, consistency in reporting. There is no agreed upon standard for endowment performance reporting and no institutional body to enforce a standard even if there was one.

Many schools report their numbers net of all costs including external management fees, internal office costs, and the endowment tax, but not all. Some report gross returns. Others subtract external management fees but not office costs or the endowment tax. Over a ten-year period that makes a difference.

Another issue. Timing of returns can be a big problem, particularly over the last few years. Public market results are computed and consolidated by investment custodians and reported to their clients usually within a month of the fiscal close.

But things get cloudier for illiquid alternative assets with no quoted prices: so-called “level 3” items. As a result, private market valuations take much longer, three months at least, and there is a fair amount of wiggle room.

Most investment teams will not know their June 30th private investment performance until September 30th or later. In some cases, much later. As a result, returns released to the media are estimates at best.

The worst idea ever

The U.S. has the greatest university system in the world thanks to generations of generous donors and visionary leaders. But, recent proposals to tax and redirect endowment earnings are, to quote NACUBO, “an unprecedented attack on the tax-exempt status of higher education institutions that reduces resources available for financial aid, research, academic support, public service, and innovation.”

Endowments are a perpetual source of support for present and future generations of students and faculty, and they take generations to accumulate.

The Oxford college community, the wealthiest university system in Europe, took about 800 years to amass an $8 billion endowment. Harvard’s $50 billion accrued in 387 years. And for the upstart $40 billion Stanford endowment, a mere 138 years.

Our universities dominate the rankings of global higher education and are key to our national preeminence. They are an American success story. Let’s not spoil the ending.

How we display our data

We have grouped our endowment performance data into four sections:

- 110 US endowments over $1bn

- 23 US endowments, $500mm to $1bn

- 5 US endowments, non-June 30 FYs

- 8 large Canadian endowments

We show ten endowments over $1 billion and three between $500 – $1 billion managed by OCIO firms (Outsourced Chief Investment Officer) which we have highlighted in green. The twenty-five female investment heads in our tables are highlighted in blue.

About the Author:

CHARLES A. SKORINA works with leaders of Endowments, Foundations, and Institutional Asset Managers to recruit Board Members, Executives Officers, Chief Investment Officers, and Fund Managers.

Mr. Skorina also publishes THE SKORINA LETTER, a widely-read professional publication providing news, research and analysis on institutional asset managers and tax-exempt funds.

Prior to founding CASCo, Mr. Skorina worked for JP MorganChase in New York City and Chicago and for Ernst & Young in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Skorina graduated from Culver Academies, attended Michigan State University and The Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey where he graduated with a BA, and earned a MBA in Finance from the University of Chicago. He served in the US Army as a Russian Linguist stationed in Japan. Charles A. Skorina & Co. is based in Tucson, Arizona.