By Massimiliano Saccone, CFA, Founder & CEO, XTAL Strategies

Private equity investors are increasingly disappointed with DPI levels, which show no sign of improvement. Distributions are running at 50% of their average historical levels, relative to NAVs[1]. In this context, LP capital should not necessarily be patient anymore. Inertia threatens to transform a long-term, patient investor mindset into irrationality.

Consequent “caveat emptor” notice: private equity advisers are updating their narratives, pushing for a more active portfolio management approach. Narratives can never be separated from incentives. For example, secondary buyers are now in hunting mode, self-interested in generating deal flow that is as cheap as possible. The appetite from secondary buyers cannot be underestimated, particularly in this context, where evergreen vehicles are in a hurry to deploy the abundant capital that is being raised.

Evergreen fund raising is actually energised by the immediate return boost that they receive from discounted secondary purchases, adopting the accounting practices that the industry has dubbed “practical expedient.”[2] Attractive reported returns have the dual benefit of generating fees and creating fundraising momentum. The fact that the IPO market is shut down and the inherent limitations (or LP caution) related to GP-led transactions is clearly putting pressure on LPs to turn capital over and recover liquidity.

It looks like the market is preparing LPs to accept discounted exits. In fact, if exits and distribution are not delivered by GPs at portfolio level, versus their marks (this is not happening, at least not yet), they can be proactively driven by LPs at the fund level. With this in mind, the objective of this article is to put LPs’ decision if/when to sell within a rational framework.

The Starting Point

A recent white paper[3] from a secondary adviser analyses tail-end private equity portfolios with a focus on U.S. buyout funds and proposes a decision-making framework based on the average annual change in TVPI (“AAC TVPI”). Its stated objective is to motivate LP portfolio managers to take a more active role in how they manage their private equity portfolios. The paper has the overall merit to remind that “a wait and hope” strategy exposes investors to a potential opportunity cost. It also has the merit of highlighting an interesting dynamic in aggregated TVPI patterns. The paper shows that the AAC TVPI turns from positive during the contractual life of funds to negative during the tail end. This suggests that not all unrealized value embedded in NAVs during the contractual life of a fund will be realized through liquidation.

It is therefore implicit in this analysis that rational secondary buyers will tend to offer liquidity at a discounted NAV price, to necessarily make the expected AAC TVPI of their portfolios positive. The extent of the discount is an important element of the decision-making process of LPs. The “true” implicit TVPI curves may be significantly less convex to incorporate early exits / liquidity costs and maintain a positive slope to full portfolio liquidation, at marginally decreasing rates.

Interestingly, in the referenced paper, the TVPI 1st quartile curve has the highest convexity, suggesting that NAV discounts could be the steepest for funds that appear to display the best performance in their early years. This seems counterintuitive. Nevertheless, if the front-loaded TVPI growth is not supported by DPIs, the quality of NAVs could be questioned and the AAC TVPI significance may decrease.

Enabling a Total Portfolio Return Perspective

The AAC TVPI approach is a simplified attempt at calculating the compound average growth rate (CAGR) of an allocation to private equity. Not being defined in proper time weighted terms, not only do AAC TVPI not allow for a proper comparison with the valuation of listed markets, they also misrepresent the increase or decrease of value of an investment and the meaningfulness of reported average data. As an example, a -5% in AAC TVPI with is a -16.7% annual loss on the NAV (assuming NAV is 30% of the TV, as it approaches the tail end years).

The adoption of accurate time-weighted return terms is a critical element to compare time-varying NAVs (and incorporate the duration effect of distributions) to all alternative expected return options. The is true not just in private equity, as the AAC TVPI simulations may be affected by reinvestment return biases. The higher the discount on exits, the more uncertain market return expectations.

If private equity is evaluated in isolation (i.e., not from a total portfolio perspective), using traditional metrics (i.e., TVPI patterns), the if/when to sell problem does not have a clear-cut solution. In other words, while AAC TVPI resemble a fully diluted version of duration-adjusted return, that approach hides the real return information that is intrinsically dependent on the NAV growth and quality.

The intuition of the AAC TVPI is nonetheless valid. The fact that private equity value peaks at around year 9 for the dataset of the referenced paper is what the duration of the contributions in the duration-adjusted return approach systematically signals. That duration marks the placeholder of the total value created by the fund, the barycentre for capital returned plus gains. This means that the residual value created after that time is marginal (does not move the needle) in a risk neutral environment.

Clearly, duration is influenced by the quality of the latest NAV. The advantage of duration-adjusted time-weighted terms is the immediate ability to gauge any asynchronous movement between NAV and the relevant overall level of market valuation. It is worth noting that rational prices tend to be influenced by the relevant beta (with alpha that should not be paid for or constitute a residual tweak to the ultimately agreed price). Once NAVs are eventually marked for expected liquidity events, duration will likely become a little shorter. Later distributions may eventually become more relevant, if they contribute to a higher return than the one implicitly priced by the market in the overall valuations level.

It is worth remembering that NAV should be assumed to be equivalent to the future expected cashflows, given the level of expected return determined by the market (at least, in a theoretical, fair price perspective). This is the exact point of difference between the AAC TVPI starting point and the total portfolio return perspective that a duration-adjusted approach brings.

Proposing a Rational Selling Framework

In purely theoretical terms, selling a properly priced (and therefore discounted to fair price) fund interest to buy a new one should be indifferent, assuming a stochastic context where alpha is not predictable and zero on average. Ultimately, in a rational framework and a given economic scenario, a secondary buyer of a fund interest would form return expectations similar to those of a primary buyer operating at the same time, for a similar type of asset.

Clearly, everyone could maintain the belief of having an edge due to superior selection skills, but under a rational decision-making framework, any subjective assumption should be removed. Alpha is easier to “display or make-up” in IRR terms, which leads to overpopulated upper quartiles. In contrast, time weighted terms show that diversification (from just above 10 funds) has a strong pull to a consequently well-calculated mean.

This fact does not imply that there is no point in selling fund interests in the secondary market (setting aside any specific comment on continuation vehicles’ transactions, which are a GP-led alternative to a traditional portfolio exit but do not escape the considerations that will follow). It instead extends to private markets the rational rule that any investment decision should be made based on expected returns (in time-weighted terms, no IRRs of all sorts, no modified Dietz). In other words, temporarily excluding eventual allocation policy boundaries and liquidity constraints, from a total portfolio perspective and a purely theoretical perspective, liquidity should be sourced from the allocation that’s expected to contribute the lower marginal return.

It is certainly possible that liquidity is best sourced using a secondary transaction from the private market allocation. Real life prices and IRR-based buyers’ incentives often create quasi-arbitrage opportunities for sellers (typically asset owners, whose portfolios are measured in time-weighted terms), if they can determine satisfactory target return and measure and exploit statistically abnormal excess return circumstances.

Statistical implications can intuitively be drawn by observing the TVPI curves of the white paper referenced earlier. Data shows that TVPIs reach, on average, an apex before the full liquidation of the relevant funds.

Selling a private fund interest at a limited or no discount, most likely in favorable market conditions (which may also propel exuberant private market valuations), may be the most rational decision before the sobering reality of the exit takes over. No one knows the future, and this is one of the often cited reasons for not selling private equity interests.

Still, information on private equity excess returns (i.e., the difference between private equity and listed equity returns in fully diluted, duration-adjusted, time-weighted terms) helps form a rational decision-making framework by leveraging the findings of a study performed on the pattern of private equity returns[4] (and not incidentally focusing on the sweet spot 7-to-9-year range of a typical private equity fund duration). Consequently, it is possible to model the future of private equity excess returns using stochastic models and probabilities, determining, for example, ranges of excess returns that are less likely to be sustainable.

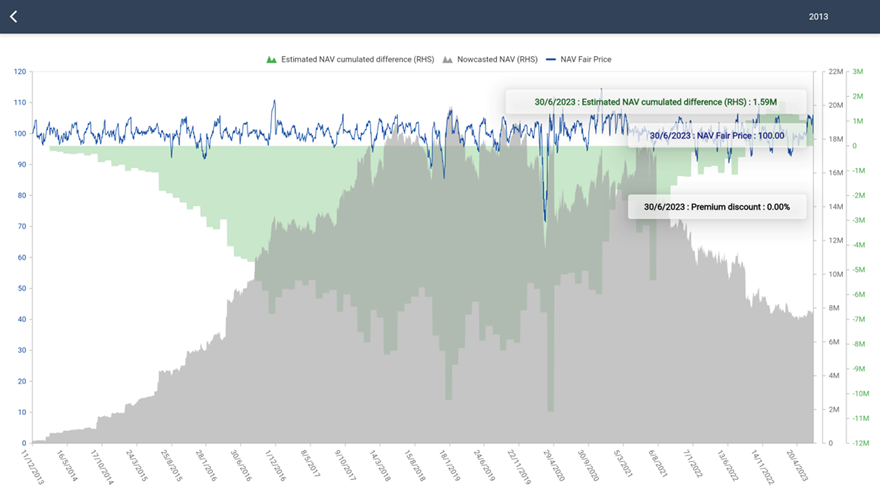

Translating research into practical application, the following Chart 1[5] illustrates the estimated real-time NAV of a normalized commitment of $10mn to a 2013 Global buyout fund (grey area - RHS), and the “cumulated error” (green bars - RHS) of the estimates versus the reported NAVs progressively delivered, to reset calculations (as shown by the indexed NAV Fair Value at 100.00, and by the Premium / discount percentage at 0.00% - LHS).

Chart 1

NAVs are the current estimate of future distributions and should properly incorporate the impact of the combination of market risk and duration. Dynamic monitoring of market risk and duration, and thus liquidity, by overlapping NAVs with a systematic, market-driven model estimating excess returns is a critical competitive resource. If excess returns embedded in NAV are not identified or do not materialize, investors may suffer from sunk opportunity costs.

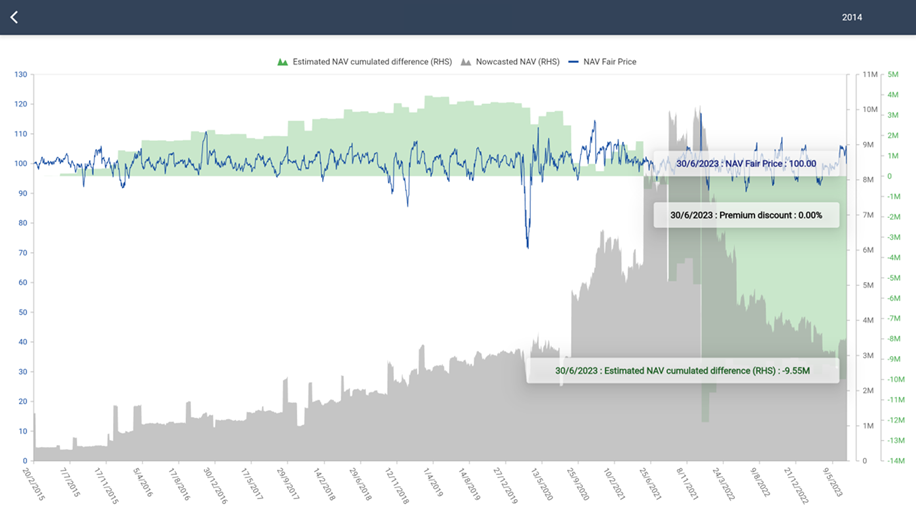

Chart 1 illustrates a case where the opportunity cost of holding to the investment was substantial. The green bars, which initially were in negative territory (representing model underestimation or excess return) by a substantial cumulated amount (up to over $10M on a $10M reference commitment and $20M NAV), ended up moving into positive territory, indicating negative excess return, as the NAV started to be liquidated. There may be several reasons for this situation. For example, the most commonly cited criticism of private equity is the backslash performance effect of stale NAVs, when listed market valuations rebound way faster, generating an implicit negative risk premium. But not all funds are the same. There are other cases, like the one of a normalized commitment of $10M to a 2013 growth fund captured by the following Chart 2[6], where valuations are kept conservative throughout the ramping up phase, and excess return emerges (in substantial and realized amounts) during the liquidation phase.

Chart 2

Clearly, model overestimation might also prompt a reassessment of the portfolio's health, revealing hidden risks rather than conservative marks.

In general (and getting back to the rational selling framework), it may be appropriate for private markets to take a probabilistic view, setting levels of unrealized excess return that may justify selling. A prudent approach could be to set an “opportunity boundary” at around the minus $4M level, as typical risk premium estimates for private equity are quantified between 200 and 400 basis points p.a.[7]. $4M out of $10M over a theoretical duration of 9 years imply 389 basis point compounded p.a.

If investors owning the fund of Chart 1 had sold their $20M NAV interests during the first quarter of 2019 at a 10% discount (conservative assumption), they would have reaped $18M plus pocketed opportunity cost savings of $11M, just probabilistically assuming that large excess returns could be mean reverting. Investors would have missed an opportunity only if the excess returns kept growing during the liquidation phase (possible but unlikely). If they had remained stable, the discount paid would have represented the insurance cost.

Such an excess return approach not only allows a rational and proactive approach to private equity portfolio management but also facilitates the integration of private equity and private markets allocations in a total portfolio perspective. This likely improves returns, quite certainly the “liquidity optionality” of the portfolio, while reducing its procyclicality.

Please note, though, that excess returns tend to increase during periods of market exuberance (and that’s when selling would reduce procyclicality) but also due to down market periods, if NAVs stay stale unless one tries to sell and the buyer bid unearths all the unwanted downside volatility of private equity.

In all market conditions, selling private equity to reallocate to private equity as in the AAC TVPI paper only works smoothly as a simulation due to the frictions and the length of both secondary sales and primary investments’ deployment processes. Evergreen structures may seem to be a solution, but not for large-scale investment transactions due to average duration and marginal return considerations (an article for another day).

It is instead more efficient and frictionless to “play” the listed and derivative markets, as the proposed rational selling framework for private equity models it in time-weighted terms.

About the Contributor

Massimiliano Saccone is the Founder and CEO of XTAL Strategies and developed its patented DARC methodology. Beforehand, he was a Managing Director, ultimately Global Head of Multi-Alternatives Strategies, at AIG Investments, after stints at DWS, Deloitte, and KPMG. A CFA charterholder, qualified accountant, and auditor, he holds a Master's in International Finance from the University of Pavia, and a magna cum laude Master's in Business and Economics from La Sapienza University in Rome. He is an active volunteer at the CFA Institute, and a Lieutenant of the Reserve of the Guardia di Finanza.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/

[1] Bain & Co. Global Private Equity Report 2025: https://www.bain.com/insights/topics/global-private-equity-report/

[5] Source: XTAL Strategies on anonymized fund data as of June 2023.

[6] Source: XTAL Strategies on anonymized fund data as of June 2023.

[7] Ghysels, Eric and Gredil, Oleg and Rubin, Mirco, Do Public Equities Span Private Equity Returns? (November 15, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5025008 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5025008