Authored by Georgina Tzanetos, Director of Content

Venezuela is a resource superpower running on extension cords.

In a world re-learning the value of energy security, Venezuelan dysfunction is quietly reshaping geopolitics – and tightening U.S. leverage.

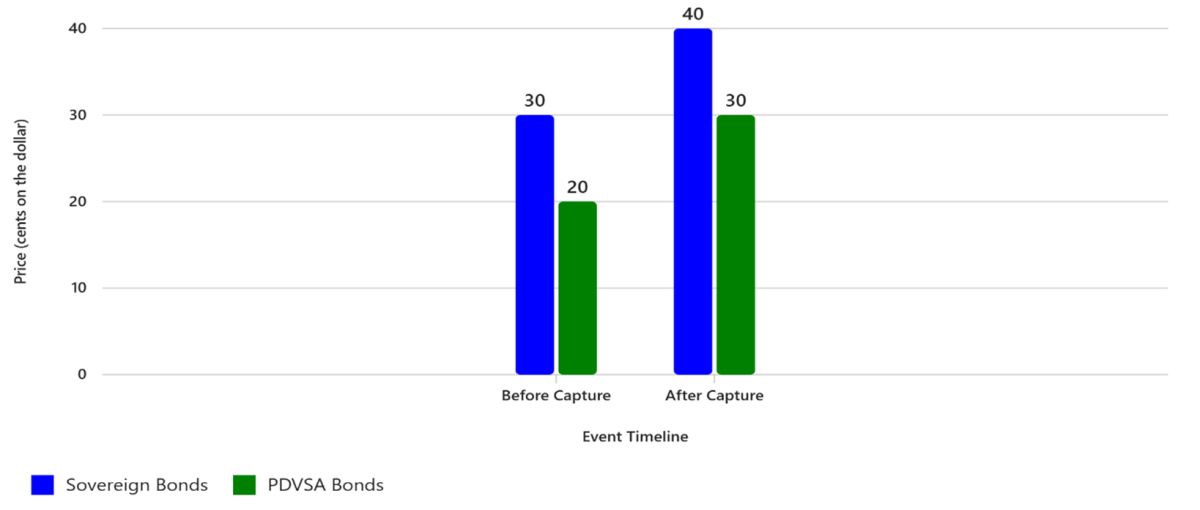

Venezuela’s petroleum sector has re-entered the headlines after the U.S. removal and detention of Nicolas Maduro in early January 2026, followed by a stated U.S. “oil quarantine” and selective licensing signals. In the immediate aftermath, defaulted sovereign and PDSVA bonds rallied sharply as event-driven funds and EM specialists moved to increase exposure, betting on eventual restructuring and a clearer path for commercial flows. Bonds issues by the Venezuelan government and state firm TDVSA surged by up to 10 cents on the dollar – or around 30% - with prices reaching approximately 40 cents for sovereign debt and 30 cents for RDVSA bonds. JP Morgan noted[1] investors are focusing less on uncertainties and more on the potential leadership shift—if Washington backs interim President Delcy Rodriguez, it could restore diplomatic ties and unlock negotiations, financing, and licenses tied to restructuring efforts. With roughly $60bn in defaulted bonds and total external debt hitting $150-170bn, the scale of restructuring remains complex.

For private market investors, the opportunity set bifurcates: (a) legal/process-driven recoveries (claims, arbitration, and debt instruments), and (b) capex-intensive upstream/midstream assets and services. The first bucket is already being monetized by hedge funds via secondary debt and litigation finance—a playbook familiar from Greece and Argentina – while the second bucket remains gated by sanctions, security, and commercial terms. Baker McKenzie [2]and Seward & Kissel[3] both caution that despite Department of Energy signals of “selective roll-back” to market Venezuelan crude, OFAC has yet to publish definitive regulatory changes, meaning counterparties still need specific licenses and robust compliance frameworks.

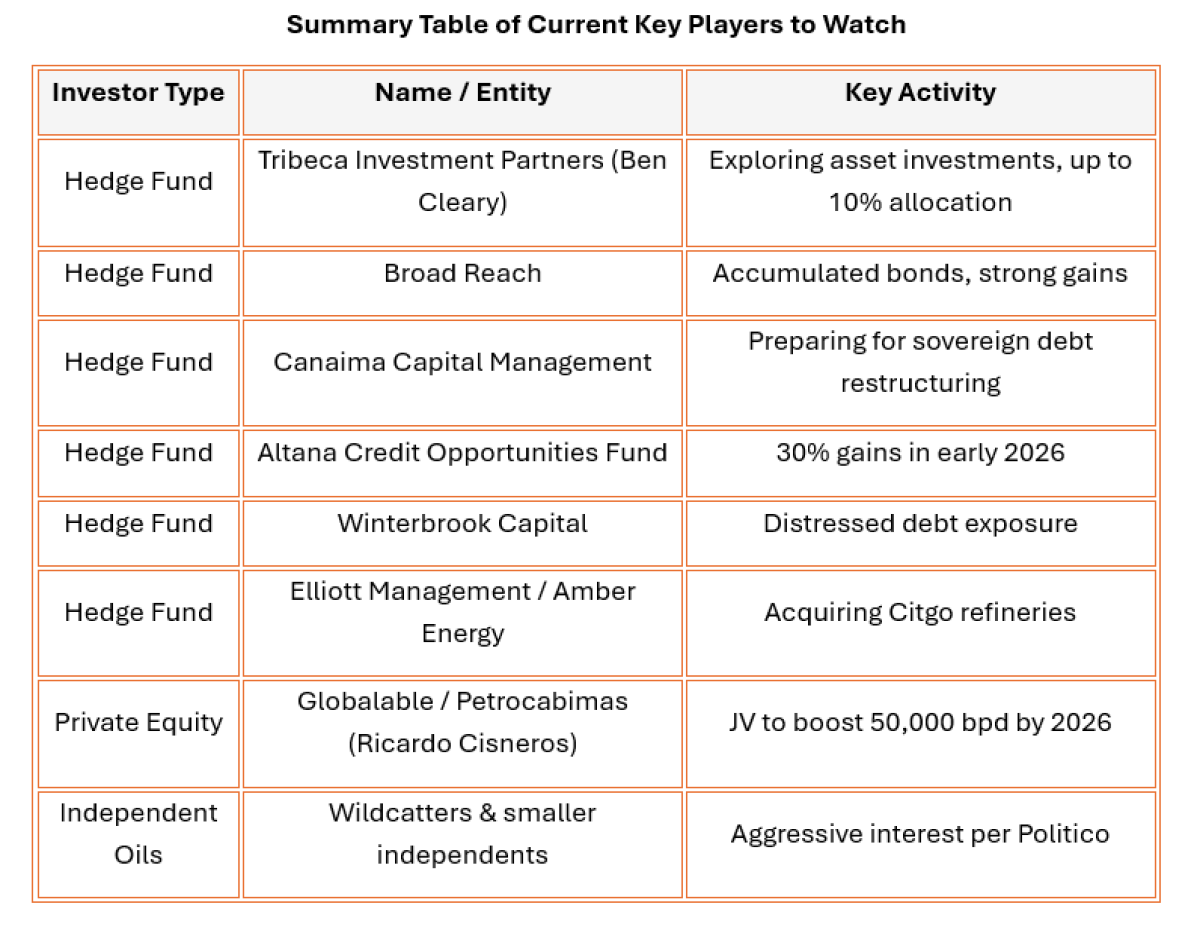

In short, the arena is not exclusively confined to ultra-risk private investors, but mainstream capital will likely stay peripheral until 1) a recognized transition authority emerges, and 2) a credible restructuring roadmap is negotiated, and 3) licensing/policy clarity reduce operational and sanctions risk. Until then, hedge funds, special-situations credit, and opportunistic private equity remain the natural first-movers in Venezuela’s oil-linked assets.

The 10-point jump in Venezuelan sovereign and PDVSA bonds signals a major windfall for funds already positioned in these instruments. Private market investors who were early to entry are already seeing returns on their risk.

Hedge funds like Altana, Broad Reach, and Tribeca—which accumulated debt at 15-30 cents—are seeing immediate mark-to-market gains of 30-50%. This validates the high-risk, event-driven strategy that anticipated a political catalyst.

For new entrants, the rally compresses upside but reinforces confidence in a restructuring path. Litigation finance and claims tied to Citgo auctions may become the next frontier, as Eliott Mangement’s[4] recent bid illustrates. Still, sanctions risk and governance uncertainty mean mainstream investors remain sidelined until regulatory clarity emerges.

Implications for Infrastructure Investing

Even with a political opening, the physical reality is sobering: Venezuela holds around 303 billion barrels of proven reserves (which is world-leading) yet produces less than 1% of global supply. This is a result of decades of underinvestment, heavy-oil complexity, and of course, sanctions. Refiners operate at a fraction of capacity; pipelines and upgraders require overhaul and heavy crude oil needs diluent (naphta/condensate) to move. The U.S. EIA and synthesis of technical constraints (extra-heavy Orinco crudes, diluent logistics, aging pipelines, and refinery outages) illustrate why near-term volume growth is bounded by infrastructure—and why specialized service companies and midstream capital may be as pivotal as the upstream.

What does this all mean? Especially for private markets?

Rystad Energy[5] estimates Venezuela would need around $53 billion in upstream and infrastructure investment over the next 15 years just to keep oil production from falling, not to grow it—simply to stay at around 1.1 million barrels a day (mb/d). It also sees a pathway to 1.4 mb/d in under 24months for about $14 billion, largely via workovers, repairs, and short-cycle projects. Returning to 3 mb/d by 2040 would require roughly $183 billion of cumulative capex (about $102 billion upstream and $81 billion for pipelines, upgraders, and other infrastructure), with meaningful participation from international capital contingent on a stable investment climate.

In other words, Venezuela is a resource superpower running on extension cords. Or a pantry full of food with a broken stove if you will.

Private equity and hedge funds thrive in these kinds of environments. This kind of opportunity will likely be historic for private markets, as upstream abundance meets downstream decay where private markets may enter, reinforce, and profit.

On the midstream/downstream side, U.S. Gulf Coast refineries have long been configured for heavy sour grade oils, and analysts note that renewed Venezuelan flows would likely benefit complex refiners (like Valero, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Marathon), potentially improving margins if barrels displace higher-cost alternatives. Oil media has cautioned that Big Oil will demand predictable contracts, investment protections, and clarity on expropriation claims—and probably a multi-year horizon—in order to commit to capex pipelines, terminals, and upgrading capacity inside the country.

Operationally, near-term bottlenecks include storage constraints under the naval “quarantine,” fire-damaged upgrader capacity, and the need for reliable diluent supply—recently sourced from Russia and U.S.-licensed flows.

The bottom line is that infrastructure investing is feasible – but only alongside enforceable contract regimes, bankable offtake and payment mechanisms, and coordinated structural upgrades. Additionally, investors will need to consider payment methods that avoid prohibited cash flows to sanctioned entities, a consideration with one foot in infrastructure problems and the other in geopolitical maneuvering.

A Shifting Chessboard Around Energy and Borders

Venezuela’s oil story in 2026 sits within two concentric geopolitical frames: U.S. sanctions/ enforcement and regional territorial tensions. At CAIA, we often report on how geopolitical forces will influence and shape capital allocation in the coming decade, and the current situation in Venezuela has potential to throw kerosene on an already tenuous geopolitical fire.

By tightening control over Venezuelan barrels, Washington reinforces its leverage in the Western Hemisphere, limiting China and Russia’s ability to use Venezuelan crude as a strategic foothold. This move also strengthens U.S. influence over Caribbean and Latin American energy flows, potentially accelerating realignment among regional players like Brazil and Colombia, who may seek closer ties with Washington to secure investment and trade stability. Globally, the situation underscores how energy security is becoming a proxy for geopolitical influence: as Europe diversifies away from Russian hydrocarbons and Asia hedges against Middle East volatility, the U.S. ability to gatekeep Venezuelan supply adds a new dimension to its energy diplomacy toolkit. Venezuela’s dysfunction is becoming a strategic lever in a multipolar energy chessboard.

On the sanctions axis, OFAC’s Venezuela program remains active: while DOE statements have hinted at selective rollbacks to market crude and import equipment, lawyers emphasize that formal licensing updates are pending, keeping compliance front-and-center for any transition.

Regionally, the Essequibo dispute with Guyana—supercharged with Exxon’s 2015 discoveries—has oscillated between saber-rattling and de-escalation under ICJ oversight. Media and policy analysis note that the U.S. intervention likely “puts on ice” near-term Venezuelan designs on Essequibo, lowering immediate risk to offshore operations and shipping lanes. Yet, the legal process continues, and any resurgence of claims would again ripple through insurance, routing, and operator risk premia.

Against this backdrop, global supply/demand matters. Many would argue that the world is currently oversupplied, with Brent in the low-60s and OPEC+ unwinding cuts; heavy-sour price differentials have compressed. That makes Venezuela’s breakevens a hurdle – reinforcing why investors demand fiscal certainty and why early gains will likely be in allocation (refining margins, debt pricing) rather than headline barrels. Near-term price impacts seem limited, but medium-term price impacts might see a successful rebuild which could pressure global prices while benefiting USGC refiners and select service names.

The gas dimension adds another layer. The Dragon field (Venezuela-Trinidad) has seen episodic licensing progress; Shell and their partners have sought waivers to resume work that could stabilize Trinidad’s LNG feedstock while threading sanctions constraints (like no direct cash to Caracas and U.S. participation). That kind of “permissioned energy diplomacy” hints at a template for narrowly tailored cooperation even under tight controls.

Is there truly a path for mainstream investors?

Yes—but it is sequenced.

Things to expect:

- Credit/distressed funds and hedge funds to keep leading on claims and debt

- Chevron and a handful of JV partners to remain the bridge for physical flows under specific licenses

- Incremental infrastructure/service investment where off-ramp compliance is clearest, and only then;

- broader institutional capital once a recognized government, a sanctions framework, and contract sanctity reduce tail risk.

For now, this is a private-markets-special-situations arena with selective industrial participation, not a wide-open theme for mainstream equity or infrastructure funds. The opportunity set skews toward distressed debt, litigation, and arbitration claims, oilfield services and logistics, and U.S. refining or downstream value-chain exposure. Execution is gated by OFAC licensing and the enforceability of contracts, making ongoing monitoring of Treasury guidance, DOE actions, and counsel alerts essential.

The timeline, as common with infrastructure investing, is measured in years rather than quarters, with capital spending ramps tied to progress on upgrades of old infrastructure. Venezuela’s oil challenge is less a question of resources than of rebuild capacity, policy durability, and time – factors that will continue to favor patient, structure-savvy capital over headline-chasing flows.

Venezuela doesn’t lack oil, but it does lack the stability and infrastructure required to turn reserves into reliable supply, a reality that continues to filter capital toward niche, risk-priced opportunities rather than broad re-entry. In a world re-learning the value of energy security, that dysfunction is quietly reshaping geopolitics—tightening U.S. leverage, redirecting trade flows, and reinforcing the strategic importance of the Western Hemisphere.

[1] Reuters. (2026, January 5). U.S. capture of Maduro could lift Venezuela, PDVSA bonds by up to 10 point, JPMorgan says. Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-capture-maduro-could-lift-ve…

[2] Baker McKenzie. (2026, January). Developments in U.S. sanctions on Venezuela. Sanctions News.

https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/developments-in-us-sanctions-on…

[3]Seward & Kissel LLP. (2026, January). Venezuela: Sanctions policy changes afoot. Seward & Kissel Publications.

https://www.sewkis.com/publications/venezuela-sanctions-policy-changes-…

[4] Fortune. (2026, January 9). Paul Singer’s Elliott Management wins Citgo auction after Maduro’s capture. Fortune.

https://fortune.com/2026/01/09/paul-singer-elliott-management-venezuela…

[5] Rystad Energy. (2026, January 6). What would it take to bring Venezuela’s oil output back to 3 million bpd? – Rystad Energy special market update. AJOT. https://www.ajot.com/news/what-would-it-take-to-bring-venezuelas-oil-output-back-to-3-million-bpd-rystad-energy-special-market-update