By Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CFP®, CIPM, FDP, Managing Director, Content & Community Strategy

If you haven’t heard by now, I’m one of those rare people who enjoys both Star Wars and Star Trek. The latest reboot of Star Trek is what got me into the franchise, and Andor Season 1-2 is some of the best Star Wars material ever written. Being a nerd is fun.

Despite both Star Wars and Star Trek having to do with space, the premise of both storylines could not be more different. Star Wars revolves around a capitalist, resource-constrained, and often-times dystopian economy and society. Survival and control is what drives character stories. On the other hand, Star Trek revolves around a socialist, post-scarcity, and utopian economy and society. Exploration and knowledge is what drives character stories.

If life imitates art, then we are quickly approaching a crossroads (hyperspace lane?) of what kind of space economy we want to develop over the next several decades. What universe do we want to live in? Star Wars or Star Trek?

The Great Expansion: A Galaxy of Growth

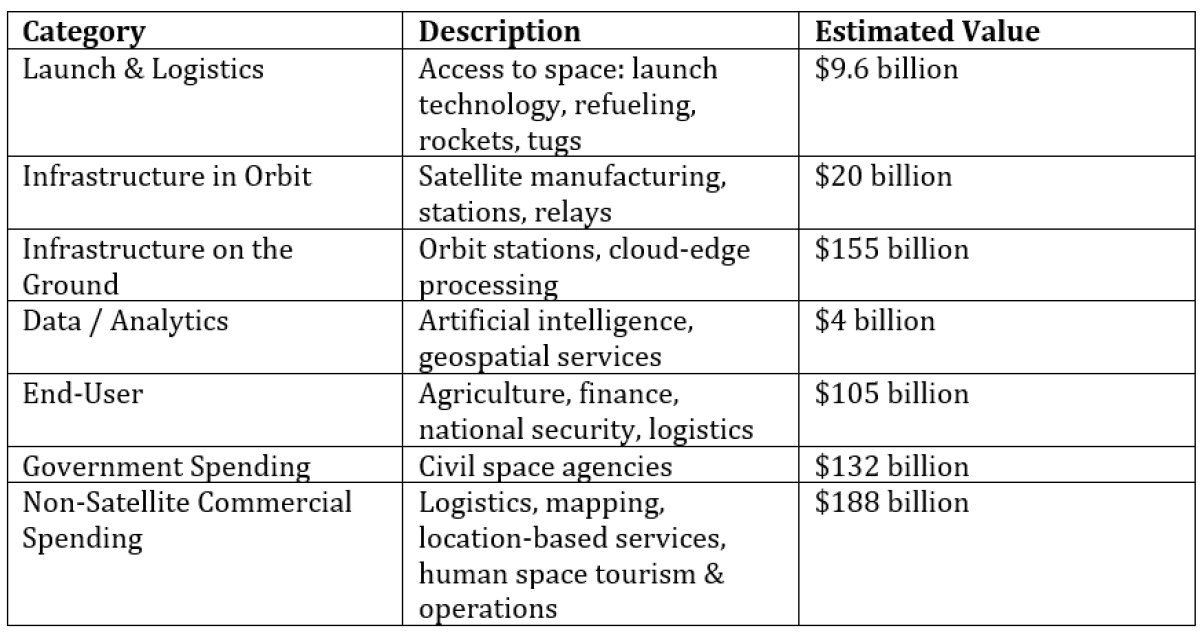

The numbers alone are staggering. The industry is already worth around ~$615 billion and could grow to $1–2 trillion by 2040. That’s the kind of growth you normally see in semiconductors, not rockets.[1] The makeup of this economy is very diverse with differing layers of complexity and growth, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Components of Today’s Space Economy

Source: Satellite Industry Association, Colossus[2]

However, the future of the industry presents both an extension of these existing categories and new ones entirely: orbital construction, asteroid mining, solar energy harvested in space, defense, and yes, even tourism (Jeff Bezos LaughTM not included with purchase)

But before we imagine ourselves as Jedi or Starfleet officers, it’s worth remembering that the future of the space economy will be shaped less by Hollywood scripts and more by the reality of the cost curve math and, importantly, the geopolitics of who gets there first. Sci-fi makes assumptions that we’ve already made it to space, whereas reality keeps us…grounded.

Cost Curves Declining at Warp Speed

Space exploration has always been about money, more accurately how much it will cost to move “stuff” off the planet. Back in 1958, the Vanguard Project cost about $1 million per kilogram to launch. By 1969, Saturn V rockets brought that down to $10,000/kg. Then came three decades of stagnation (and even regression), with costs creeping back up to $25–50,000/kg.

Motorola’s Iridium constellation in the late 1990s showed just how unsustainable this was: a pioneering LEO satellite network for phones, but so expensive that the company went bankrupt when customers couldn’t foot the bill. A perfect example of where “if you build it, they will come” didn’t actually work out but rather became a famous HBS case study.

Enter SpaceX. The Falcon series in the 2000s and 2010s pushed costs down to around $1,600/kg, thanks to reusable boosters. Suddenly, instead of throwing away your hardware every flight, you could refurbish and relaunch it. But SpaceX isn’t done there. Starship, slated for operational use in 2026, aims to bring costs below $100/kg, with some more aggressive estimates of $10/kg. That’s the cost of sending a small package.

In economics terms, this is the “forcing function.” In the Cold War, the forcing function was national security. In the early 2000s, it was entrepreneurial disruption. Today, it’s both — geopolitics and business colliding in orbit.

A New Hope From a Long Time Ago

We’ve seen this movie before — or at least a prequel of it. In 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the world with Sputnik. The U.S. scrambled to catch up, creating DARPA, NASA, and pouring money into STEM education. The primary motivator for the beginning of the space race of the 60s was government-led to promote national interests.

The 1960s became a tennis match of “firsts”: Yuri Gagarin orbits Earth, John Glenn responds. The Soviets put the first person in space, and the Americans send a man to the moon. These were incredible showcases of innovation, but they were also expensive. At its peak, the U.S. space budget was nearly 5% of federal spending. The Soviets, meanwhile, helped bankrupt themselves trying to keep pace.

None of this was about profit, rather it was about ideology and prestige. Capitalism versus communism. One system versus another. Which means the first space race was, in many ways, a Star Trek narrative: exploration driven by state ambition, not shareholder return.

Federations and Enterprises

Today, the geopolitical lines are again being drawn at the same time that SpaceX’s success is welcoming greater competition. Instead of a Cold War between the U.S. and Soviet Union, there are many more countries, companies, and overlapping interests.

On one side are the Artemis Accords[3], launched in 2020 with seven countries and now up to 56 signatories. The purpose of Artemis is to establish a framework for safe and cooperative space exploration, building on the spirit of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Running in parallel is the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS)[4], founded in 2021 by China and Russia with 17 countries and 50 institutions involved. The purpose of this partnership and collective is more focused: building a lunar research base through the 2030s.

Despite their different, and some might argue complementary, objectives, there is little overlap between these two initiatives. As the world realigns behind multiple powers, geopolitical power will influence the way countries (and therefore companies) operate. The United States is still barred by law (the Wolf Amendment) from collaborating with China, while Europe seeks greater autonomy in the space race with projects like IRIS². And of course, The Middle East, the capital of capital, continues hedging its bets by selectively participating in both U.S. and Chinese partnerships.

This isn’t the neat binary rivalry of the Cold War. Instead, it’s a multipolar shuffle, where cooperation and competition blur together depending on who’s launching, who’s funding, and who’s regulating.

The Jedi vs. Mercenaries

Not only is this no longer a binary rivalry, it’s become a matrixed one. Companies have become increasingly globalized over the past few decades, but deglobalization is likely to lead to increased redundancies at the sovereign level and open up opportunities for the private sector to participate in the next space race.

SpaceX has both reduced the costs of business and increased demand for satellite services with Starlink, making it a dual-purpose business model and a geopolitical tool. The company’s role in Ukraine showed just how much influence a private player can wield. Similarly, the launch market is now crowded: Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, ULA, ISRO, ESA, and more. Finally, new industries are emerging: orbital data centers (the cloud literally in the cloud), in-space manufacturing, lunar mining, and asteroid robotics.

And with that comes messy questions. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 bans sovereign claims and weapons of mass destruction, but says little about who owns lunar minerals or asteroid metals. Most importantly, it raises questions we haven’t had the luxury to ask until now: Can Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos legally stake a claim to an asteroid? Can China declare de facto sovereignty by building a lunar research base?

This is where the Star Wars analogy takes hold. In that universe, the economy is competitive and resource-constrained, and trade routes spark wars. Sound familiar?

What Universe Do We Want to Build?

The first space race was about ideology. The new one is about economics layered onto geopolitics. The U.S. and China the poles, but now the EU seeks independence, the Middle East hedges its bets, and India is rising. Further, the private sector is no longer just a contractor for the government. Instead, they’re strategic actors with strong influence over policy and public opinion.

So, to end where I started… which storyline are we in?

If we’re heading toward a Star Trek future, space becomes a cooperative, exploration-driven endeavor — an economy and society of discovery, with nations working together to expand knowledge.

If we’re heading toward a Star Wars future, space becomes a competitive, resource-constrained battleground — a capitalist economy where trade routes, mining rights, and corporate empires shape the plot.

Live long and prosper, and may the Force be with you.

P.S. Listen to our recent Capital Decanted episode that delves deep into space investing.

About the Contributor

Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CFP®, CIPM, FDP is Managing Director, Content & Community Strategy at CAIA Association. His industry experience lies in private wealth management, where he was responsible for asset allocation, portfolio construction, and manager research efforts for high-net-worth individuals. He earned a BS with distinction in finance and a master of finance from Pennsylvania State University.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/