The National Audit Office of the government of the UK (their GAO, if you will) has expressed its concern that the government is risking substantial liabilities in its approach to infrastructure projects. A report issued in mid-January, Planning for Economic Infrastructure, worried in particular about the degree to which the government has offered guarantees to potential private investors in infrastructure to save these investors from a range of risks. As the NAO notes, guaranteeing someone against a risk in this way shifts that risks – and in this instance, the risks in question would be borne by the taxpayers “if the underlying cost risks are not managed well.” The broad meaning of “infrastructure” employed in the NAO discussion includes water, waste disposal, energy, rails, highways, and other institutions. In the continuation of a development that dates back at least to the mid-1980s, an initiative given formal expression during Tony Blair’s time on Downing Street, the government now expects that £310 billion [US $490 billion] will be expended over the next three years in infrastructure projects. HM government doesn’t intend to do all that spending itself. Rather it is looking to private companies for 64 percent of it.

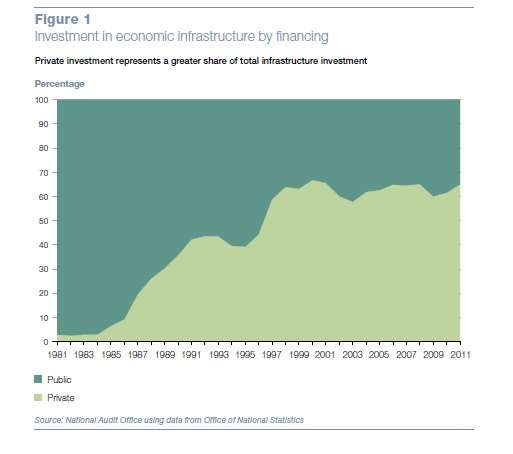

The National Audit Office of the government of the UK (their GAO, if you will) has expressed its concern that the government is risking substantial liabilities in its approach to infrastructure projects. A report issued in mid-January, Planning for Economic Infrastructure, worried in particular about the degree to which the government has offered guarantees to potential private investors in infrastructure to save these investors from a range of risks. As the NAO notes, guaranteeing someone against a risk in this way shifts that risks – and in this instance, the risks in question would be borne by the taxpayers “if the underlying cost risks are not managed well.” The broad meaning of “infrastructure” employed in the NAO discussion includes water, waste disposal, energy, rails, highways, and other institutions. In the continuation of a development that dates back at least to the mid-1980s, an initiative given formal expression during Tony Blair’s time on Downing Street, the government now expects that £310 billion [US $490 billion] will be expended over the next three years in infrastructure projects. HM government doesn’t intend to do all that spending itself. Rather it is looking to private companies for 64 percent of it.  As the above graph indicates, the private percentage of infrastructure financing rose steadily from about 1986 through 1999, despite a dip in the years 1994 and ’95. Through the years of the new millennium, though, the percentage has been roughly constant in the neighborhood of 64 to 66 percent. “Demand for infrastructure is set to increase,” said Amyas Morse, the head of the NAO, when that office released its report, “fueled by population growth, technological progress, climate change and congestion.” Well over half of the projected £310 billion, or about £176 billion, would relate to energy, and most of that (£123 billion) to electricity generation. In what seems a bit of stiff-upper-lip understatement, the NAO’s report says, “Energy projects are often large and complex and the costs are difficult to evaluate.” Indeed. EDHEC on Infrastructure Debt Only days after the release of this report, on January 22, the EDHEC-Risk Institute weighed in, expressing the view that infrastructure construction risks don’t need guarantees from the public sector, they need “scientific portfolio construction.” EDHEC, through its NATIXIS Research Chair on infrastructure debt investment, now makes the point that the risks associated with construction are mostly a function of who will bear that risk. This is the old “moral hazard” issue. When does a safety net become a hammock? Or, to put it another way, if the U.K. simply decides that its infrastructure program in general is Too Big to Fail: what could go wrong? EDHEC will present a paper on infrastructure debt investment at a conference in London, March 2013, the culmination of three years of academic research on the nature and the performance of debt instruments in this field, and on the potential benefits for institutional investors of including such fixed-income instruments in their portfolios. The bottom line of EDHEC’s research is that there is no need to create new public sector liabilities. Institutions will invest because it is rational for them to invest, because “adding some construction risk to an infrastructure debt portfolio” moves a portfolio toward the efficiency frontier, and omitting the whole category moves the portfolio away from that frontier. And on Infrastructure Equity Another recent related product of Edhec is a report on “efficient benchmarks for Infrastructure Equity Investments,” by Frédéric Blanc-Brude. Blanc-Brude helps clarify the nature of some of the risks involved from the point of view of the investing institutions. He considers, for example, the UK’s water utilities, which operate within a regime of price cap regulation. This has, especially over the last quarter century, reduced the return for investors in the affected utilities from 8 percent to 5 percent today. The critical fact about infrastructure investment, though, in Blanc-Brude’s view, is that it is both non-linear and predictable. It is non-linear in that projects have a lifecycle “that implies different risks and different return profiles for the different components of the capital structure.” But this is itself a predictable datum, “contrary to the classic case in corporate finance” where equity risk is the least predictable. These unusual features of infrastructure projects are precisely what allow for a scientific balancing of the portfolio. The investment strategist can “focus on the contractual and regulatory characteristics of underlying infrastructure” and can design an efficient portfolio including such equity.

As the above graph indicates, the private percentage of infrastructure financing rose steadily from about 1986 through 1999, despite a dip in the years 1994 and ’95. Through the years of the new millennium, though, the percentage has been roughly constant in the neighborhood of 64 to 66 percent. “Demand for infrastructure is set to increase,” said Amyas Morse, the head of the NAO, when that office released its report, “fueled by population growth, technological progress, climate change and congestion.” Well over half of the projected £310 billion, or about £176 billion, would relate to energy, and most of that (£123 billion) to electricity generation. In what seems a bit of stiff-upper-lip understatement, the NAO’s report says, “Energy projects are often large and complex and the costs are difficult to evaluate.” Indeed. EDHEC on Infrastructure Debt Only days after the release of this report, on January 22, the EDHEC-Risk Institute weighed in, expressing the view that infrastructure construction risks don’t need guarantees from the public sector, they need “scientific portfolio construction.” EDHEC, through its NATIXIS Research Chair on infrastructure debt investment, now makes the point that the risks associated with construction are mostly a function of who will bear that risk. This is the old “moral hazard” issue. When does a safety net become a hammock? Or, to put it another way, if the U.K. simply decides that its infrastructure program in general is Too Big to Fail: what could go wrong? EDHEC will present a paper on infrastructure debt investment at a conference in London, March 2013, the culmination of three years of academic research on the nature and the performance of debt instruments in this field, and on the potential benefits for institutional investors of including such fixed-income instruments in their portfolios. The bottom line of EDHEC’s research is that there is no need to create new public sector liabilities. Institutions will invest because it is rational for them to invest, because “adding some construction risk to an infrastructure debt portfolio” moves a portfolio toward the efficiency frontier, and omitting the whole category moves the portfolio away from that frontier. And on Infrastructure Equity Another recent related product of Edhec is a report on “efficient benchmarks for Infrastructure Equity Investments,” by Frédéric Blanc-Brude. Blanc-Brude helps clarify the nature of some of the risks involved from the point of view of the investing institutions. He considers, for example, the UK’s water utilities, which operate within a regime of price cap regulation. This has, especially over the last quarter century, reduced the return for investors in the affected utilities from 8 percent to 5 percent today. The critical fact about infrastructure investment, though, in Blanc-Brude’s view, is that it is both non-linear and predictable. It is non-linear in that projects have a lifecycle “that implies different risks and different return profiles for the different components of the capital structure.” But this is itself a predictable datum, “contrary to the classic case in corporate finance” where equity risk is the least predictable. These unusual features of infrastructure projects are precisely what allow for a scientific balancing of the portfolio. The investment strategist can “focus on the contractual and regulatory characteristics of underlying infrastructure” and can design an efficient portfolio including such equity.

←

Back to Portfolio for the Future™

Investing in Britain’s Infrastructure: With and Without Guarantees

January 28, 2013