The Bank for International Settlements, the services and coordinating body for central banks, has taken a politely-worded crack at what it calls “unconventional monetary policies” of the Fed and the European Central Bank – mostly the Fed – in a new paper.

The Bank for International Settlements, the services and coordinating body for central banks, has taken a politely-worded crack at what it calls “unconventional monetary policies” of the Fed and the European Central Bank – mostly the Fed – in a new paper.

BIS Paper #78, by Madhusudan Mohanty, contends that the “highly accommodative monetary policies in the major advanced economies” are wreaking havoc among the emerging markets. Lowering the exchange rates in the U.S. and Europe as far as the respective central banks have, while allowing exchange rates to float, has increased the value of the domestic currency in a number of EMs, increasing volatility in the process. Even the hint of backing off of the ultra-low rates has the contrary impact.

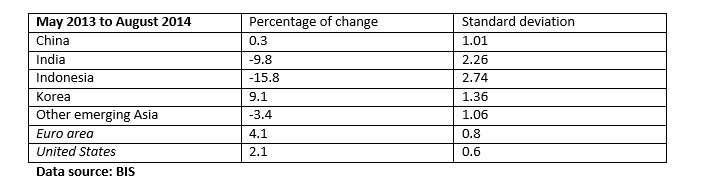

EM challenges may be triggered by announcements as to the plans of advanced-economies’ central banks. The table below gives the movement of several nominal exchange rates in the period since the U.S. Federal Reserve’s now-notorious “tapering” announcement in May 2013, along with the standard deviation. The numbers below are selected from a broader table provided in the BIS paper. The rates from the Euro area and The United States are at the bottom, Asian EM nations on top.

India and Indonesia showed significant depreciation, as did the nations in the “other” category, during this period.

Since currency revaluations have an immediate impact on output, the central banks of the EM economies “may directly respond to actual or imminent changes in advanced economies policy rates by changing their own policy rates.”

Policy Rates

The average policy rate in economies with fixed exchange rates has moved very closely with the federal funds rate in the U.S. This is to be expected. Hong Kong for example has a currency board arrangement which has led to a close synchronization of short-term interest rates with the federal funds rate. What may be less expected is that the central banks in countries with a flexible exchange rate show the same tendency.

Further, short term policy rates in the EMs have been lower than one would have expected if one’s expectations had been keyed to such standard benchmarks as the Taylor rule. So it cannot be said that the correlation of EM central banks with the moves and announcements of the Fed is simply a matter of the convergence of the business cycles.

Sometimes, it appears capital flows are driven by psychological factors. The changes in investor sentiment in much of the world after the Fed tapering announcement were very rapid, and arguably cannot be explained in macroeconomic terms, the BIS says. This was especially so for the so-called “fragile five” – Turkey, Brazil, India, South Africa, and Indonesia – identified by a research analyst at Morgan Stanley in the summer of 2013 as most susceptible to changes in investor sentiment, a prediction that may have become self-fulfilling.

The BIS has surveyed central bankers in EMs, and it reports that many of them are worried about asset prices as a channel for spillovers. “[As] the monetary policy of the advanced economies has started to determine domestic bond and equity prices, traditional pricing tools have lost their anchoring role, and asset prices are becoming increasingly dependent on expectations for the future path of U.S. monetary policy. Thus, even apparently marginal changes to policy may have the potential to create large-scale market volatility.”