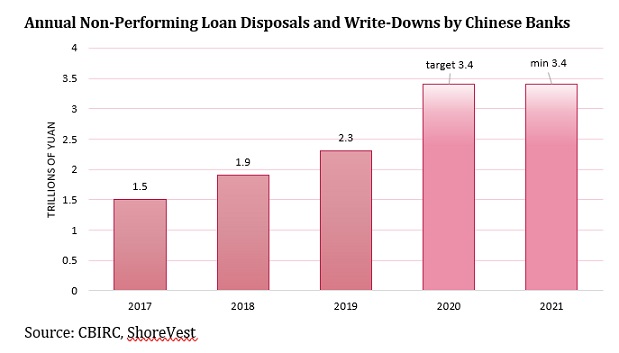

By Dinny McMahon, Economic Advisor to ShoreVest For the last few years, China has been involved in a slow-moving cleanup of its banking system, creating vibrant distressed debt and special situations opportunities for investors. Those opportunities have been heightened by the pandemic which is forcing banks to accelerate their pace of bad loan disposals. And yet foreign capital is significantly underrepresented among investors in this space. While the operating environment has unquestionably improved since China's last debt disposal cycle, significant barriers to success remain. This piece will outline China's advantages relative to other markets, illustrate the scope of China's bad loan issue, outline how the operating environment for distressed debt and special situations has improved, and explain why it remains a challenging environment for foreign fund managers. THE PANDEMIC When compared to other major economies around the world, China presents an immediate opportunity for distressed debt and special situations investing. China has put the worst of the pandemic behind it. The economy has stabilized, and economic activity has assumed a degree of normalcy which is currently unthinkable in most developed countries. On the back of this success, China's financial regulators have restored monetary policy with a more normal footing. While interest rates are at rock bottom in most developed economies, in China interbank lending rates have returned to pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, US and EU measures to mitigate the pandemic's fallout have suppressed borrowing costs and investor returns, thereby keeping alive firms that under normal circumstances would require restructuring. For the time being China stands out as one of the few places where investor returns aren't distorted by monetary authorities' emergency measures, and where distressed debt and special situations opportunities have reemerged. The opportunities for private credit investing are particularly pronounced. Private sector firms have traditionally struggled to tap credit from the formal banking system. For a period following the global financial crisis they were able to close the gap by borrowing from a nascent shadow banking system, but a sustained crackdown since 2016 has meant that credit available from shadow banking sources has massively contracted. Hence, private firms that need credit—whether it be to take advantage of post-pandemic M&A opportunities, or for working capital to support their recovery—have few options available to them. We estimate that the prevailing interest rate which private companies are willing to pay is in the mid- to high teens for a twelve-month senior secured loan, almost twice the level we saw in prior years. Meanwhile, the sheer volume of nonperforming loans (NPLs) banks dispose of annually makes China the biggest distressed debt market in the world. In 2019, NPL and non-core asset disposals in Europe (the second largest market) came to EUR 102.4 billion ($125 billion), compared to about $160 billion in NPL disposals (not including write-downs) by China’s banks. That said, there is no way of knowing the precise scale of China’s NPL problem. According to the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), at the end of June the NPL ratio for China’s banking system was 1.94%, up slightly from 1.86% from the end of 2019. That is relatively low by international standards, partly because China’s official NPL data has long understated the true level of bad debt, and partly because of sustained efforts in recent years to dispose of NPLs. The pandemic has further complicated any effort to estimate the true level of banks’ distressed debt with authorities encouraging banks to exercise forbearance in their treatment of borrowers. However, forbearance is due to end on March 31, 2021, and the banking regulator has warned financial institutions to prepare for a coming wave of NPLs. Even though official NPL data suggests that China's banks don't have a problem with asset quality, NPL disposal data says something different. China was already in the midst of an NPL disposal cycle when the pandemic hit. According to data disclosed by the CBIRC, in the four years from 2016 to the end of 2019, Chinese banks disposed of 6.7 trillion yuan ($965 billion) worth of nonperforming loans, a figure that includes write-downs, debt-to-equity swaps, and the transfer of NPLs to third parties. That is equivalent to approximately 4.9% of the total volume of outstanding loans at the end of the period.  Signs of mounting stress in the financial system signal that we are only at the early stages of the NPL recognition and disposal process. After two decades of relative financial stability, China's financial authorities have intervened to prop up four of China’s 50 biggest banks since mid-2019. Further interventions in the years ahead are likely, all the more so as banks deal with the fallout from COVID-19. Banks have already been instructed to ramp of the pace of NPL disposals. In August, the head of the CBIRC set a target for NPL disposals this year of 3.4 trillion yuan, up almost 50% from 2.3 trillion yuan of disposals in 2019. He said disposals need to rise even further in 2021. THE CHALLENGES Clearly, China presents a unique opportunity, but investing in China poses risks and challenges that differ from other markets. They also differ from those of China's last debt disposal cycle that lasted from 2000 to 2008. During that previous cycle, foreign investors were routinely stymied by local political interests that did not want local assets sold off by creditors (be they domestic or foreign). Consequently, loan workouts often took far longer than anticipated, resulting in lower returns as claims got held up in the courts and judges found in favor of local interests. Today, creditor rights have been significantly strengthened by a series of Beijing-led improvements, and the authorities not only support the involvement of foreign investors but encourage it. Crucially, the litigation process and the courts’ willingness to enforce creditors’ rights has significantly improved. Once a court has taken a case, enforcement rules mandate that it should take no more than 18 to 24 months before a creditor receives the proceeds from auction (compared to it commonly taking four to five years a decade ago). For most NPL cases the legal process is transparent, the steps involved well-documented and straightforward, and despite some variation between regions, the courts’ implementation is efficient. While the legal and political environment has improved, investing in Chinese distressed debt remains difficult. There is perhaps no clearer indication of that than the limited role foreign fund managers play in the market. According to a PwC survey published early 2020, eight foreign funds acquired 14 NPL portfolios in 2019 for a combined value of about $1.1 billion, up from 13 portfolios worth $900 million in 2018. China’s NPL market is arguably larger than any other in the world, and yet the role of foreign funds is disproportionately small, with the vast majority of NPL transaction volumes involving small domestic buyers. Tellingly, some of the biggest names in global distressed debt investing have not established a presence in China. The reason is clear: while the barriers to entry are low, the barriers to success are high. While anyone can approach an asset management company—the bad banks tasked with acquiring bank NPLs in bulk—and buy a portfolio of NPLs, it requires experience and local insight to design the portfolio and price the collateral in a way that will deliver desired returns. Moreover, having the relationships to source a viable portfolio, and having it efficiently serviced requires time, experience, and sufficient in-house capacity to do the requisite due diligence. Sourcing NPL and special situations investment opportunities is complicated by market fragmentation. There are literally hundreds of sellers marketing NPL portfolios, and no central repository where that information is available to all market participants. Given that NPL disposals are mostly concentrated in the hands of four large AMCs that operate nationally, that may seem counterintuitive. But within those firms, marketing of NPL portfolios is done by dozens of quasi-autonomous units that are responsible for discrete geographical jurisdictions. Those units have authority to negotiate directly with buyers and routinely compete against each other to get their NPLs sold. Compounding the complexity are an additional 60 local AMCs that operate at a provincial level in parallel to the four national AMCs, as well as the commercial banks themselves which also seek to attract buyers. For any would-be market entrant, developing a robust deal-sourcing network takes years, presenting a meaningful barrier to entry. Servicing loans is equally complicated. China’s NPL market is still at an early stage and so lacks the expertise and professionalism of more established markets. Moreover, China lacks institutional NPL servicing companies that operate nationally. Finding local partners—whether they be a law firm, servicer, or appraiser—requires time, trust, and oversight, and is complicated by needing to find suitable partners in every location where a fund has NPLs. It also requires funds to have the in-house expertise and manpower necessary to monitor their partners’ work and vet it when necessary. Investing in NPLs can’t be outsourced to third parties and managed remotely. Beyond legal expertise, local in-house expertise navigating the idiosyncrasies of China’s business environment is also essential, since the ultimate exits for NPLs are more often negotiated workouts with obligors or sales to third party buyers. Such out of court exits are even more vital when legitimate claims to assets may be slowed down or held up indefinitely by courts wary that an asset's disposal might cause social instability—perhaps by affecting employment or housing—which is an all-consuming concern of China's authorities. The social stability ramifications of a loan aren’t always immediately apparent and require extensive experience and local knowledge to weed out. CONCLUSION Investing in Chinese distressed debt and special situations presents a unique opportunity. While measures designed to combat the pandemic continue to distort credit markets in most large economies, China has already restored monetary policy a more normal footing. Moreover, inefficiencies in the allocation of credit, and the authorities' commitment to accelerating the pace of banks' NPL disposal, mean there is a ready—and expanding—supply of deals. And the government has proven itself willing to improve the operational environment and committed itself to supporting foreign investment. And yet, China remains a difficult place to invest. Experience can overcome structural impediments, but few foreign fund managers have the necessary experience from the few deals they have negotiated in recent years. Consequently, the market will continue to offer enticing opportunities, but the scope of foreign capital to tap those opportunities will remain relatively limited. Dinny McMahon is an Economic Advisor to ShoreVest, working with the firm to analyze the dynamics of China’s credit markets, and assisting the investment committee in its strategic directions. In this role, Dinny actively analyzes the state of China’s commercial banking system, the volume and nature of the banks’ non-performing loans and clean up efforts, as well as other macroeconomic matters affecting ShoreVest’s deal sourcing and execution. Dinny McMahon spent 10 years as a financial journalist in China, including six years in Beijing with The Wall Street Journal, and four years with Dow Jones Newswires in Shanghai, where he also contributed to the Far Eastern Economic Review. In 2015, he left China and The Wall Street Journal to take up a fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a think tank in Washington DC, where he wrote China’s Great Wall of Debt: Shadow Banks, Ghost Cities, Massive Loans, and the End of the Chinese Miracle, a book about the Chinese economy that was published in 2018. Until recently he was a fellow at MacroPolo, the Paulson Institute’s think tank, where he wrote about China’s efforts to clean up its financial system. Dinny currently does research on China’s financial system for financial services firms. Dinny is fluent in Chinese, having studied the language in Beijing and Kunming, and followed by a year at the Johns Hopkins SAIS campus in Nanjing where he studied international relations in Chinese. For inquiries, please email inquiries@shorevest.com.

Signs of mounting stress in the financial system signal that we are only at the early stages of the NPL recognition and disposal process. After two decades of relative financial stability, China's financial authorities have intervened to prop up four of China’s 50 biggest banks since mid-2019. Further interventions in the years ahead are likely, all the more so as banks deal with the fallout from COVID-19. Banks have already been instructed to ramp of the pace of NPL disposals. In August, the head of the CBIRC set a target for NPL disposals this year of 3.4 trillion yuan, up almost 50% from 2.3 trillion yuan of disposals in 2019. He said disposals need to rise even further in 2021. THE CHALLENGES Clearly, China presents a unique opportunity, but investing in China poses risks and challenges that differ from other markets. They also differ from those of China's last debt disposal cycle that lasted from 2000 to 2008. During that previous cycle, foreign investors were routinely stymied by local political interests that did not want local assets sold off by creditors (be they domestic or foreign). Consequently, loan workouts often took far longer than anticipated, resulting in lower returns as claims got held up in the courts and judges found in favor of local interests. Today, creditor rights have been significantly strengthened by a series of Beijing-led improvements, and the authorities not only support the involvement of foreign investors but encourage it. Crucially, the litigation process and the courts’ willingness to enforce creditors’ rights has significantly improved. Once a court has taken a case, enforcement rules mandate that it should take no more than 18 to 24 months before a creditor receives the proceeds from auction (compared to it commonly taking four to five years a decade ago). For most NPL cases the legal process is transparent, the steps involved well-documented and straightforward, and despite some variation between regions, the courts’ implementation is efficient. While the legal and political environment has improved, investing in Chinese distressed debt remains difficult. There is perhaps no clearer indication of that than the limited role foreign fund managers play in the market. According to a PwC survey published early 2020, eight foreign funds acquired 14 NPL portfolios in 2019 for a combined value of about $1.1 billion, up from 13 portfolios worth $900 million in 2018. China’s NPL market is arguably larger than any other in the world, and yet the role of foreign funds is disproportionately small, with the vast majority of NPL transaction volumes involving small domestic buyers. Tellingly, some of the biggest names in global distressed debt investing have not established a presence in China. The reason is clear: while the barriers to entry are low, the barriers to success are high. While anyone can approach an asset management company—the bad banks tasked with acquiring bank NPLs in bulk—and buy a portfolio of NPLs, it requires experience and local insight to design the portfolio and price the collateral in a way that will deliver desired returns. Moreover, having the relationships to source a viable portfolio, and having it efficiently serviced requires time, experience, and sufficient in-house capacity to do the requisite due diligence. Sourcing NPL and special situations investment opportunities is complicated by market fragmentation. There are literally hundreds of sellers marketing NPL portfolios, and no central repository where that information is available to all market participants. Given that NPL disposals are mostly concentrated in the hands of four large AMCs that operate nationally, that may seem counterintuitive. But within those firms, marketing of NPL portfolios is done by dozens of quasi-autonomous units that are responsible for discrete geographical jurisdictions. Those units have authority to negotiate directly with buyers and routinely compete against each other to get their NPLs sold. Compounding the complexity are an additional 60 local AMCs that operate at a provincial level in parallel to the four national AMCs, as well as the commercial banks themselves which also seek to attract buyers. For any would-be market entrant, developing a robust deal-sourcing network takes years, presenting a meaningful barrier to entry. Servicing loans is equally complicated. China’s NPL market is still at an early stage and so lacks the expertise and professionalism of more established markets. Moreover, China lacks institutional NPL servicing companies that operate nationally. Finding local partners—whether they be a law firm, servicer, or appraiser—requires time, trust, and oversight, and is complicated by needing to find suitable partners in every location where a fund has NPLs. It also requires funds to have the in-house expertise and manpower necessary to monitor their partners’ work and vet it when necessary. Investing in NPLs can’t be outsourced to third parties and managed remotely. Beyond legal expertise, local in-house expertise navigating the idiosyncrasies of China’s business environment is also essential, since the ultimate exits for NPLs are more often negotiated workouts with obligors or sales to third party buyers. Such out of court exits are even more vital when legitimate claims to assets may be slowed down or held up indefinitely by courts wary that an asset's disposal might cause social instability—perhaps by affecting employment or housing—which is an all-consuming concern of China's authorities. The social stability ramifications of a loan aren’t always immediately apparent and require extensive experience and local knowledge to weed out. CONCLUSION Investing in Chinese distressed debt and special situations presents a unique opportunity. While measures designed to combat the pandemic continue to distort credit markets in most large economies, China has already restored monetary policy a more normal footing. Moreover, inefficiencies in the allocation of credit, and the authorities' commitment to accelerating the pace of banks' NPL disposal, mean there is a ready—and expanding—supply of deals. And the government has proven itself willing to improve the operational environment and committed itself to supporting foreign investment. And yet, China remains a difficult place to invest. Experience can overcome structural impediments, but few foreign fund managers have the necessary experience from the few deals they have negotiated in recent years. Consequently, the market will continue to offer enticing opportunities, but the scope of foreign capital to tap those opportunities will remain relatively limited. Dinny McMahon is an Economic Advisor to ShoreVest, working with the firm to analyze the dynamics of China’s credit markets, and assisting the investment committee in its strategic directions. In this role, Dinny actively analyzes the state of China’s commercial banking system, the volume and nature of the banks’ non-performing loans and clean up efforts, as well as other macroeconomic matters affecting ShoreVest’s deal sourcing and execution. Dinny McMahon spent 10 years as a financial journalist in China, including six years in Beijing with The Wall Street Journal, and four years with Dow Jones Newswires in Shanghai, where he also contributed to the Far Eastern Economic Review. In 2015, he left China and The Wall Street Journal to take up a fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a think tank in Washington DC, where he wrote China’s Great Wall of Debt: Shadow Banks, Ghost Cities, Massive Loans, and the End of the Chinese Miracle, a book about the Chinese economy that was published in 2018. Until recently he was a fellow at MacroPolo, the Paulson Institute’s think tank, where he wrote about China’s efforts to clean up its financial system. Dinny currently does research on China’s financial system for financial services firms. Dinny is fluent in Chinese, having studied the language in Beijing and Kunming, and followed by a year at the Johns Hopkins SAIS campus in Nanjing where he studied international relations in Chinese. For inquiries, please email inquiries@shorevest.com.

Interested in contributing to Portfolio for the Future? Drop us a line at content@caia.org