This article was originally published by ShoreVest on April 12, 2021. It is a comparative analysis of the risk/return profile of Chinese private debt. The paper addresses competing private credit products, creditor risks, assumptions about credit protections, the size of the market, the lack of competition, and potential fit within a globally diversified portfolio.

Historically the bulk of institutional capital allocated to private credit has been focused on North American and European markets. But with the continued low interest environment, many investors are looking to Asian credit markets, and in particular, China, for higher yields. The size of China’s debt markets, and in particular the private credit market (whether in non-bank lending or buying non-performing loans) is significant, growing, and underserved, making it an opportunity that can no longer be ignored.

The traditional assumption that Western markets are less risky is also being called into question due to their increasing prevalence of covenant-lite and higher leverage ratio transactions. Furthermore, China’s legal landscape is getting more predictable across a number of key dimensions, thus improving creditor protections and making loan recovery processes much easier to underwrite.

China’s private credit market also benefits from having low correlations with traditional portfolio allocations, while delivering attractive returns relative to developed market private credit vehicles. Of course, the actual results a particular investor may receive will depend on careful selection of the right manager.

Market Size, Growth, and Lack of Competition

The total Chinese bond market is approximately $15T in size and has become the second largest in the world (BIS, World Bank, Dec 2019). Its public debt market is increasingly viewed as a stable and viable source of diversification away from more developed bond markets. From a returns perspective, Figure 1 illustrates the improving performance of China Corporate Bonds when compared with U.S. Investment Grade Corporates.

Fig. 1

| YTD | 1 Year | 3 Year | |

|

S&P China Corporate Bond Index |

0.82 | 1.09 |

3.55 |

|

Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index |

-2.90 | 0.37 |

4.84 |

Source: Morningstar, S&P Dow Jones; as of 4/09/21

Chinese private credit is viewed as a newer and more niche asset class, but investments in this space (which are typically secured by collateral such as real estate) have been a well-performing part of some institutional managers’ funds for over a decade. The strategy can be executed in the form of either direct asset-backed lending to corporations, or by purchasing non-performing corporate loans (NPLs) which are typically senior secured.

In sections below, this paper will discuss the relative attractiveness of Chinese private credit’s risk/return profile from a global perspective. Driving its unique risk/return profile are three overarching factors: (1) the volume of debt in the market, (2) forecasted growth in volume of opportunities, and (3) the lack of competitors, especially relative to developed markets:

1) Market Size

Unlike the U.S. or Europe, China does not have a large number of competing institutional private credit funds, and therefore its private credit market size cannot be approximated simply by adding up the AUM of private credit managers. Instead, after China’s post-GFC credit boom levelled off, the shadow banking system (an amalgamation of trusts, wealth management product platforms, peer-to-peer lenders, etc.) arose quickly to fill the lending gap not met by commercial banks. According to the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), the shadow banking system reached $12.9T at the end of 2019. But the Chinese government seems to prefer that institutional private fund managers fill this need, rather than unregulated shadow banking groups that raise money from retail investors who may not understand the risks of alternative credit products. In recent years, the government’s resolve to reduce the size of the shadow banking market is clearly seen in the trust and entrusted loan market where, according to CEIC data, total loan value as of Q1 2021 is 22% lower than it was three years earlier. Over this same period China’s GDP grew almost 20%. With the government shrinking the shadow banking market to mitigate its systemic and social risks (while also implementing stricter banking regulations on traditional bank lenders), there is an increasing demand for private credit funds to step into this approximately $12.9T market (see ShoreVest’s China Debt Dynamics (Apr 2021): “Sustained Shadow Banking Contraction Creating Private Credit Opportunities”).

As for the NPL market, research by PWC combining the total official level of NPLs, special mention loans, and NPLs held outside the commercial banks concluded that there was at least $1.5T of stressed assets in the market as of February 2020. A 2019 estimate formulated by a researcher from Tsinghua University National Research Center put the number even higher. And the Financial Times states that the NPL ratio for the entire banking system is more likely between 8.2% and 12.4%, or $2.6T and $3.9T.

2) Growth

In terms of capital allocations to private credit, Asia Pacific is set to be one of the fastest-growing regions globally over the next 5 years. Given China’s dominance in the Asian fixed income market, the country is well positioned to capture a significant percent of the estimated 21.2% annual private debt AUM growth for the next five years.

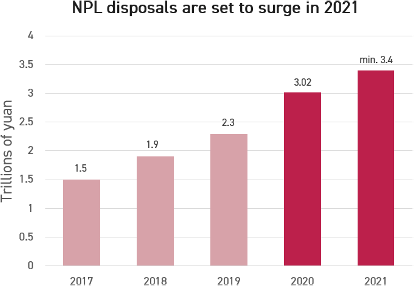

The Chinese NPL market is particularly well positioned. Not only is the amount of stressed assets in China growing, but the pace of disposal is increasing (see Figure 2), and the country’s banks are highly motivated to dispose of these assets (see ShoreVest’s China Debt Dynamics (Oct 2020): “Dealing With a Coming Surge in Nonperforming Loans”). In 2020, Chinese banks disposed over RMB 3T of NPLs – twice the 2017 number.

Fig. 2

Source: CBIRC, local media

3) Competition

While the Chinese private credit market is growing, it remains highly fragmented and significantly less competitive than U.S. and European markets. Focusing again on the NPL market, most transactions by international funds remain relatively small, between $50-200M, and far more of the buyers are domestic onshore investors who usually invest between $5-50M in each deal. In 2019 there were approximately 14 foreign investors that invested a total of $1.1B of capital into what is at least a $1.5T market. The lack of success by foreigners to penetrate the market has been due to three primary barriers: (1) the years it takes to develop onshore networks to generate quality deal flow within the PRC (as opposed to Hong Kong or more remote places), (2) the years it takes to develop strong local servicing capability and an understanding of how to navigate the legal system, and (3) the integration of onshore deal teams with offshore investment committees has proven difficult.

Like NPLs, special situation lending has similar foundational barriers. As a result, other than deals done by RMB funds or longstanding platforms, most China special situation lending by foreign investors is accomplished through one-off deals that deploy capital from regional mandates, not China-focused vehicles. Foreign firms investing in special situations deployed $2.5B in capital in 2019. Compared with the size of the $12.9T shadow banking sector, foreign credit funds make up a relatively small percent of the market.

Investment Risks: Developed Markets vs China

Investors in global capital markets have long assumed that the Chinese credit markets are riskier than more developed countries such as the U.S. While it is true that in years past, China’s legal system remained unpredictable and difficult to navigate (especially for foreign funds with limited experience), these factors have improved significantly in China.

Furthermore, at the product level, Chinese asset-backed private credit generally affords far more margin of safety than is typically found in the West. For instance, Chinese private credit funds often target LTVs in the range of 30-50%, whereas leverage levels in the West are much higher.

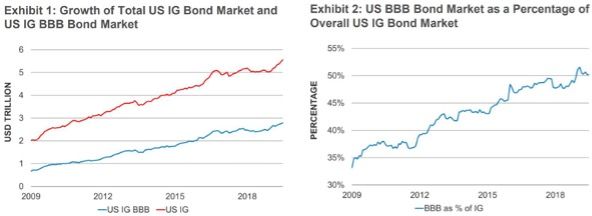

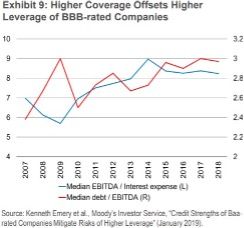

Since 2009, the size of the overall U.S. investment grade (IG) corporate bond market has grown 1.76x, surpassing $5.5T as of June 2019. The BBB rated segment of this market has more than tripled in size to $2.8T, now representing 50% of all IG debt, up from 33% in 2009 (Figure 3), characterizing a serious decline in the overall credit quality of IG debt as evidence by the higher leverage ratios (Figure 4).Fig. 3

Source: Blackrock

Fig. 4

Source: Blackrock

Meanwhile, if we compare typical asset backed lending standards in the U.S. versus China, we find that the macro- prudential regulations are much stricter in China and ensure that there is more room for recovery in the event of default. For example, in residential mortgages, a typical U.S. mortgage LTV starts at 80% LTV, whereas the maximum LTV in China is 80%—in practice, due to numerous macro-prudential regulations, the realizable LTV in China is significantly lower. Furthermore, the standard banking products in China do not include the ability to re-lever (e.g. Home Equity Line of Credit products). As for non-residential assets, a typical CRE LTV in the U.S. is 75% or higher whereas in China the effective LTV is usually below 30%. This is due to a requirement by Chinese banking regulations that the principal of the loan be capped by the sum of the rental income that is generated during the maturity of the loan (so a typical loan term of around five years on an asset with 4% cash flow yields would result in an LTV of 20%). Additionally, real estate prices in most Chinese markets remain strong even after the pandemic, thus underpinning the value of the collateral.

Lastly, there is a common misconception that the Chinese legal environment does not offer strong creditor protections and is unpredictable. However, the legal system for enforcing credit in China has improved significantly in the last decade. For example, PWC reported that NPL workout times take 12-30 months on average, as opposed to 4 to 5 years a decade ago (although ultimate recovery will depend on the skill of the investment manager).

Fit within a Globally Diversified Portfolio

As part of either an established private credit portfolio or a new investment, asset-backed Chinese private credit can broaden portfolio diversification and offer uncorrelated returns with major capital markets. Onshore China Credit markets are highly uncorrelated with other capital markets including Asia High Yield and Asia Equities. The chart in Figure 5 illustrates the low correlation relationship with other global as well as domestic asset classes.

Fig. 5

| Asian High Yield Credit | China USD Credit | Global IG Corp (USD) | Global HY Corp (USD) | US Equities | Asian Equities | |

| China Onshore Credit |

10% |

18% |

14% |

6% |

2% |

2% |

Sources: Blackrock, WIND, Bloomberg, 5-year as of end April 2020. China Onshore Credit: China Bond Credit Index; Asian High Yield Credit: JP Morgan Asian non-Investment Grade Index; China USD Credit: JP Morgan China Credit Index; Global IG Corp (USD Hedged): Bloomberg Barclays Global Corporate Index; Global HY Corp (USD Hedged): Bloomberg Barclays Global HY Corporate Index; U.S. Equities: S&P 500; Asian Equities: MSCI AxJ.

In addition to the benefits of low correlation, Chinese private credit can offer portfolio return diversification. Compared with U.S. monetary policy, China remains accommodating, but unlikely to provide additional economic stimulus. This will likely cause a greater number of distressed debt opportunities to develop that in turn could lead Chinese private credit strategies to outperform developed market peers. In addition to increased supply, the tightening in shadow bank credit availability is impacting the cost of capital that companies are willing to pay for a senior real estate backed loan: in late 2020 we saw this number reach high teens vs low-teens only a year ago.

Outperformance Relative to Competing Strategies

As with any other investment, an evaluation of target risk/return should be scrutinized relative to competing investment options. Below are three strategies that are exposed to similar underlying risks or have an investment focus similar to asset-backed Chinese private credit.

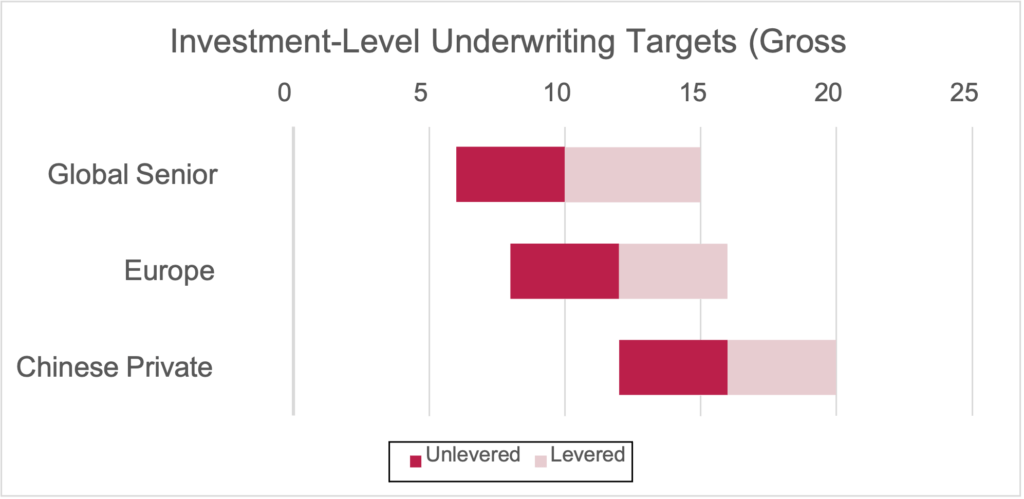

China Private Credit

- Vehicle Type: Private Fund

- Investment Focus: Senior secured first lien asset back loans

- Target Deal Level Returns: 12-16% (unlevered); 16-20% (levered)

As with private debt strategies globally, a China credit manager’s ability to achieve target returns is highly dependent on sourcing capabilities and execution skill throughout market cycles. Nevertheless, the target returns for the space are achievable, at least with experienced local managers.

Senior Secured Global Direct Lending (U.S. and Europe)

- Vehicle Type: Private Fund

- Target Deal Level Returns: 6-10% (unlevered); 10-15% (levered)

The structure of U.S. or European direct lending differs from Chinese private credit in material ways. Besides the location of the target firms, a significant difference is that much of the private credit in these markets is cashflow based and not secured by first liens on real estate. With U.S. and European lenders, there is a greater emphasis on forecasted cash flow metrics (as opposed to a focus on liquidation value of real estate collateral). U.S. and European investments more commonly use EBITDA adjustments such as addbacks, which allow for assumptions on the ability of the borrower to pay back the debt based on the future growth of the company. Furthermore, although some such strategies are called “senior secured,” the underlying collateral is often not real estate. Senior secured lenders in Chinese private credit typically focus more on metrics such as LTV margin of safety ratios (ideally 36-50% LTV) at the deal level, backed by actual real estate (as opposed to future cash flows or intangible collateral like equity or IP). Additionally, credit managers in the West often allow for lighter covenants compared with asset-backed Chinese private credit.

European NPLs

- Vehicle Type: Private Fund

- Target Deal Level Returns: 8-12% (unlevered); 12-16%, (levered)

European NPLs and asset-backed Chinese private credit share some similarities such as underlying collateral, which is typically real estate, and a focus on LTV ratios at the deal level. Within Europe, investors are particularly focused on Southern Europe (Italy, Greece, and Spain) where the greatest volume of NPLs have been concentrated in recent years. There are similarities with target returns, but differences with legal structures and regulatory policies.

The two most significant differences between Chinese and European NPLs are the market size and competition. Europe’s total NPL volume stood at $621B as of June 2020 but is expected to grow with the pandemic. In any event, it is difficult to see Europe surpassing China’s multi-trillion-dollar NPL market (especially once China adds its own pandemic-related NPLs to the existing stock, which is expected to begin in 2021).

The second major difference is the level of competition. The European NPL market is highly competitive with each auction generally attracting a large amount of competition. By contrast, experienced Chinese NPL firms generally not only hand-pick loans to be included in a portfolio for auction, but often are the only bidders on those portfolios. Target deal level returns for the above strategies (both unlevered and levered) are shown below in Figure 6.

Fig. 6

Source: Cambridge Associates, PWC, ShoreVest

Investment Partner Selection

There are factors to consider when selecting a manager. First, the partner should have an excellent onshore deal sourcing network and experience working out loans throughout cycles in China. This means strong relationships with regional banks, asset management companies, lawyers, loan servicers, and leadership at middle market industry leaders. Forming these networks is essential in sourcing consistent, high-quality deal flow for NPLs or special situations loans.

Second, investment committees or other executives with full deal discretion should be located within the PRC, because almost invariably the Chinese corporate executives needing a private loan, or the sellers of an NPL portfolio, want to speak with the fund’s decision-makers directly in their own language and culture. The local team should be capable of assessing investment risks that are unique to China and moving quickly when an opportunity is identified.

Last, investors should look for a partner with not only a proven track record of strong risk adjusted returns through market cycles, but also institutional quality and transparency (something many local RMB investors fall short on). Because navigating Chinese investments has very little in common with other Asian countries, investors who want exposure to Chinese private credit would best served by selecting an institutional partner with experience focusing specifically on China, instead of more general Asia mandates.

Legal Information and Disclosures

This letter expresses the views of the author as of the date indicated and such views are subject to change without notice. ShoreVest Partners has no duty or obligation to update the information contained herein. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. ShoreVest Partners believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, it cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based. This letter, including the information contained herein, may not be copied, reproduced, republished, or posted in whole or in part, in any form without the prior written consent of ShoreVest Partners.