By Keith Black, Ph.D., CAIA, CFA, FDP, Managing Director/Program Director of FDP Institute.

Historically, the financial system has been enabled through a network of centralized counterparties, such as banks and brokerage firms. These counterparties facilitate borrowing and deposits as well as enable trading and custody of securities. These counterparties typically have a physical domicile where they are required to comply with local or national banking laws and securities regulations. Each nation has its own currency, which brings currency conversion costs to global trading. Each currency has its own government, central bank, monetary and fiscal policies, which sometimes lead to hyperinflation and currency debasement, with the most extreme cases seen in Zimbabwe and Venezuela. There are also concerns about the risks that these counterparties bring to the global financial system, which was demonstrated during the Global Financial Crisis. These centralized counterparties also earn significant fees which can be reduced through a decentralized system.

Each of these counterparties keeps a private, centralized ledger of all of the assets and liabilities in each customer’s account. Should that ledger be compromised due to a fire, flood, cyberattack, or insolvency of the counterparty, clients may struggle to recover or identify their personal assets. The goal of a distributed ledger system is to have multiple copies of these asset and liability accounts available on a publicly accessible network maintained by redundant record keepers. In the digital asset world, these distributed ledger systems are termed blockchains. If the distributed ledger on each blockchain is maintained by 1,000 globally distributed counterparties, the risk of failure of a single counterparty is substantially reduced.

Each public blockchain is designed to be global, distributed, and immutable. Once a transaction is recorded on a blockchain, it can’t be changed. Each miner or validator, those local operators who maintain a copy of the distributed ledger, records transactions to the blockchain. The term cryptocurrencies is derived from the idea that these networks are secured by cryptography, which encrypts data to ensure that it can not be changed. A focus of these cryptographic mathematical puzzles are hashes, an example of which is the 64 character output from bitcoin’s SHA-256 hash algorithm (f7225388c1d69d57e6251c9fda50cbbf9e05131e5adb81e5aa0422402f048162).

On the bitcoin blockchain, transactions are gathered for 10 minutes and then published as a block. The transaction records in each block will include the sender’s bitcoin address, the receiver’s bitcoin address, and the size of the transaction. When either of these addresses transacts again in the future, the ledger keeper will look back to this transaction to view the available balance of each market participant. The key innovation is that this structure prevents the double spending of each currency or token.

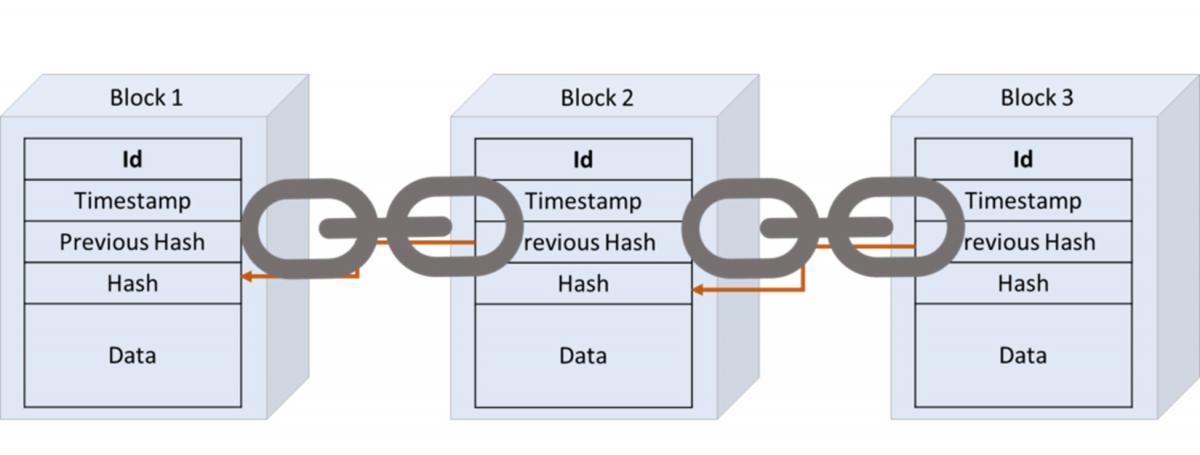

Immutability of these records is enforced when each block is identified with a hash which is a unique identifier of the information contained in that block. The hash of the previous block is included in the next block, which chains the blocks together with a common identifier. If a single character in a block is modified, the hash will completely change and the mismatch between the two blocks will be recognized by the ledger keepers. Once this error is noted, the ledger keepers will go back into their records and replace the mismatched or recently changed information with the correct, original version of the transaction log.

Illustration of a Blockchain

Source: https://www.paiementor.com/blockchain-explained-application-payments/

Why Are Blockchains Expanding from Cryptocurrencies to Digital Assets?

Given that a blockchain is simply a way to secure and store information, each blockchain can be designed to track the ownership of a specific asset. There are a wide variety of assets or information that can be tracked using blockchains. Off-chain assets may include real-world assets, such as the contents and payments of shipping containers or the ownership of specific real estate properties. On-chain assets may include cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin or tokens such as ether.

What Are the Risks?

Custody is one of the key risks in digital assets. Cryptography is used to encrypt secure transactions using public keys and private keys. Each user of a blockchain will disclose their public key whenever receiving value. It is safe to share your public key, as it is similar to an email address as a unique destination for others to send information or value. In order to send value from an address, the user’s private key is used to verify that the asset may be removed from the account. This is similar to an email password but designed to be much more secure. Due to the size of the hash and the complexity of the cryptography, there is no evidence that a brute force methodical guessing or hacking system has been able to compromise private keys. There is evidence that cyberattacks have successfully stolen private keys and digital asset values after breaking into PCs or cryptocurrency exchanges (such as Mt. Gox) which may not have been well defended by secure passwords and careful users. That is, the bitcoin blockchain itself has not been hacked, but users have lost value from their bitcoin wallets through insecure storage at the user or exchange level.

What Is a Hardware Wallet?

The safest way to secure your digital assets from theft is through the use of a hardware wallet. In this truly decentralized process, the user downloads the digital assets into a piece of computer hardware, such as a USB key, and keeps the hardware in a secure location that is not accessible through the Internet. If the user’s private keys are nowhere in their phone, computer, or any Internet-accessible location, there is no chance that a hacker can find those private keys and take value from the user’s account. Some users will keep the USB drive in a safe deposit box, with perhaps a paper copy of the private key (separate from the public key or USB drive) in another bank or safe location. While this is the safest way to secure digital assets from theft, users with hardware wallets are trusting themselves with the physical custody of those digital assets. If the USB key is lost due to fire or flood, if the user dies or becomes incapacitated without disclosing the private key to their family, or if the private key is simply lost or forgotten, there is no way to recover the value. When the goal is to remove centralized counterparties from the financial system, there is no password recovery help desk or reset process.

Many users will trust the custody of their digital assets to an exchange, such as Gemini, Coinbase, or Binance. In these centralized exchanges, users can exchange fiat currency for cryptocurrencies and digital assets as well as exchange one digital asset for another. These exchanges are termed on-ramps, as they allow fiat currency to be added to the account through the use of credit cards or bank transfers and then converted into digital assets. Exchanges may perform many services for crypto users that are familiar from traditional banks or brokerage firms, such as custody of assets, ability to process trades, deposits and withdrawals, KYC/AML controls, name beneficiaries, and reset passwords. While this may be convenient, it also introduces custody risk, as the exchange stores your private keys. There’s a famous saying: “Not your keys, not your crypto.” If anyone else, including a centralized exchange, has access to your private keys, you are not 100% guaranteed to fully control the value in your account.

About the Author:

Keith Black has over thirty years of financial market experience, serving approximately half of that time as an academic and half as a trader and consultant to institutional investors.

He currently serves as Managing Director and Program Director for the FDP Institute. Prior to joining the FDP Institute, Keith served as Managing Director of Content Strategy for the CAIA Association, and previously at Ennis Knupp + Associates, Keith advised foundations, endowments and pension funds on their asset allocation and manager selection strategies in hedge funds, commodities, and managed futures. Prior experience includes commodities derivatives trading, stock options research and Cboe floor trading, and building quantitative stock selection models for mutual funds and hedge funds.

Dr. Black previously served as an assistant professor and senior lecturer at the Illinois Institute of Technology. He has contributed to the CFA Digest, and has published in The Journal of Wealth Management, The Journal of Trading, The Journal of Investing, and The Journal of Alternative Investments, among others. He is the author of the book “Managing a Hedge Fund,” as well as co-author of the second, third, and fourth editions of the CAIA Level I and Level II curriculum. Dr. Black was named to the Institutional Investor magazine’s list of “Rising Stars of Hedge Funds” in 2010.

Dr. Black earned a BA from Whittier College, an MBA from Carnegie Mellon University, and a Ph.D. from the Illinois Institute of Technology. He has earned the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation and was a member of the inaugural class of both CAIA and FDP members.