By Shreekant Daga, CAIA, CFA, FRM, Associate Director and Authorized Signatory for CAIA India LO.

In the fund management business, the Limited Partner (LP) has a very dominant position as they are often attributed as the asset owners. A General Partner (GP) or an asset management company (AMC) is largely an allocation vehicle. Within the varying levels of size, a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) is a bigger influence given their ability to tear large cheques.

A SWF is a government/state owned investment fund comprised of the money or surplus created by that entity to meet desired allocation outcomes which may have a combination of societal, commercial, and objective oriented rationale.

While most large economies have a SWF to meet investment outcomes, India or Indian states or employment unions do not. India as a sovereign uses a different model which can be labelled as public-private participation. In India there is President’s portfolio which comprises of all the investment which the government has made straight into creation of certain companies which directly do business. These companies are labelled as a Public Sector Unit (PSU) in India. Example: The largest bank in India by asset size is a Public Sector Bank (or PSU) formed in 1955.

Likewise, India Inc.’s role in creation or contribution of a pure-play investment vehicle has also been in partnership with other financial institutions. Example: National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) is a government backed fund created in 2015 to meet long term infrastructure needs of India having institutional LPs from India and other foreign countries. Similarly, SIDBI Ventures which was created in 1999 is a WOS of SIDBI (a MSME bank) which has the government as an anchor shareholder.

Government can certainly channel capital through these entities to cater to several long-term projects which may not bode well with private institutions given the term and return expectancy. Additionally, the central bank (Reserve Bank of India) of India also governs money flow by altering the definition of priority sector lending (PSL). Example: Banks lending to startups are now considered to be part of the PSL requirement limits.

The Indian startup ecosystem is expanding and despite the disagreement on the rank, data vendors will point that trajectory has been unidirectional. While the number of startups registered with the government a decade back was under 350 is now well over 90,000. The participation of the fund management industry to facilitate capital formation has complimented the growth of entrepreneurship, it may be noted that the growth of these businesses has been limited to size since the ecosystem doesn’t have domestic players who can tear large cheques. This market feature has led to a glass ceiling for the growth of sizeable startups. Indian VC/PE funds rarely have the ability to co-invest in up rounds with valuation reaching $500 million. This leaves the start-up ecosystem to look outward and pivot to the parameters measured by global funds to sustain growth. Example: A lesson learnt over the past decade for foreign startups investors in India is that market share gained by cash burn is not sustainable and the old school positive cash flow metrics is key to sustainability.

India being one of the largest five economies in the world doesn’t have institutions of size to depict. Fortune Global 500 list ranks companies by total revenues for their respective fiscal years ended on or before 31 March. As on the current year (2023), India has only 8 companies on that list. The best ranked Indian company is Reliance Industries at 88. The same is true for the private markets with unicorn creation translating to a compulsory involvement of a foreign strategic/financial investor. Perhaps a large Indian SWF if established can facilitate the startup funnel to break the glass ceiling for size and scale.

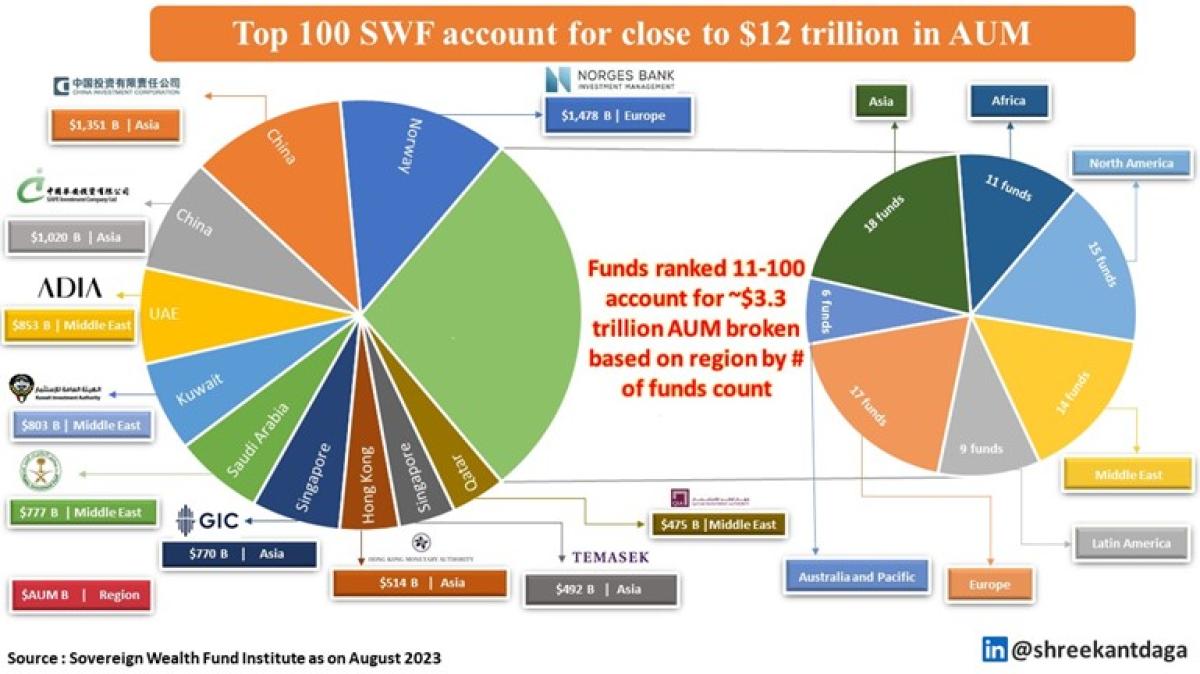

Historically a SWF has been setup as a solution for a country with budgetary surplus with the first one being established as early as 1953 by Kuwait to invest excess oil revenues. It is estimated that there are more than 175 SWFs today which have close to $12 trillion in assets under management (AUM). Of these the largest 10 SWFs own close to $8.5 trillion in AUM. India runs a fiscal deficit every year, but a SWF creation can happen through budgetary planning exercise. In recent years alternative investments have gained prominence within the SWFs given that the horizon and appetite allow investment direction that no other entity form allows.

If India is to be part of the Asian century dream, then she needs to find avenues to generate employment at scale and lift and broaden the wealth pyramid. Encouragement of entrepreneurship as a trait and scalable startups as an institution combined could lead India to be part of the Asian century dream. Could the creation of a SWF also harness the reality that for an economy of India’s size and projectile, big is beautiful!?

About the Author:

Shreekant Daga is a CAIA, CFA and FRM charter holder. Shreekant pursued Bachelor’s in Management from Narsee Monjee College and later did his Master’s in Management from Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies (JBIMS). He also holds a Master’s in Commerce from Mumbai University. He is an alumnus of Bombay Stock Exchange Training Institute, having completed the certificate program on capital markets. He has also acquired several certificates from the National Stock Exchange in Financial Markets.

Prior to joining CAIA Association, Shreekant had gathered experience in Structured Finance. His experience encompasses investment banking in debt capital markets, handling stressed assets, global RMBS deal evaluation, securitization, stress assets rating and mutual fund rating. Shreekant has worked with organizations such as ICICI Bank, Deutsche Bank Group and India Ratings and Research (Fitch Ratings). In mid-2018, he joined the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) Association, the international leader in alternative investment education and provider of the CAIA designation, as Associate Director at India liaison office wherein he looks after India operations.

Shreekant has been a visiting faculty at JBIMS and has taught subjects such as Fixed Income, Global Markets & Financial Institutions and Structured Finance. He has been involved in mentoring students at his alma mater for their year-long projects. He has also graded final year MSc students of Mumbai University on their year-long projects. He has also featured in newspapers, magazines, press releases and article on the web. His name also features on the list of educational professionals on the MHRD website. True to the cross function that he maintains with education and industry, Shreekant has 4 research papers presented and published at international forums and journals respectively.