By John Brynjolfsson[1]

By John Brynjolfsson[1]

Prologue

A Chinese proverb, which could certainly be applied to the examination of monetary policy, advises: “if you want to know what the water is like, don’t ask the fish.”

I take this advice to heart, as it fit my approach to life—step back and look at the big picture from outside a system to gain an understanding of how it works. Not only is this more gratifying intellectually, I’d suggest it provides better insights into understanding how things may evolve given new circumstances, and allows one to be more attuned to what kinds of black swans might arise.

With this as a starting point, I look to illuminate the current state of affairs in interest rates, inflation and bond yields.

Central banking has long been well understood. Paper money, it is said, was invented in China, and dates back to the 10th Century. The oldest central bank, the central bank of Sweden, dates back 345 years to 1668. The Bank of England dates back to 1694, predating Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and the US Declaration of Independence by about a century. In the following centuries, as the globe industrialized and economies transformed, modern central banking was introduced onto the landscape in 1913 when the Federal Reserve System, known colloquially as “the Fed” was created by the US Congress.

Its creation was a reaction to the boom-and-bust cycle associated with the bubbles created by unbridled private credit creation and the panics that inevitably followed. The youngest of the major modern central banks, the ECB, was created by the Maastricht Treaty, and is a mere adolescent at 15 years old. Other major central banks are the Bank of Japan, the Peoples Bank of China and the Swiss National Bank. Coming back to the Fed, it is currently 99 years old, and on December 23, 2013 we can celebrate its 100th birthday!

In 2013 the concept of central banking will face its greatest test, starting with the Fed.

Fiat Money

Modern fractional reserve central banking seems to be a great improvement to the prior fragmented US regime. Though the great Depression of the 1930s forced some tinkering with this system, in particular introduction of the FDIC to federally guarantee deposits and Keynesian prescriptions to address chronic unemployment, the system has worked exceedingly well.

So central banking had evolved from being on the gold standard in prior centuries, to fragmented fractional reserve banking, to fully fiat money central banking (when the gold standard was officially abandoned in 1971.)

There is nothing conceptually wrong with fiat money. Paul Volcker demonstrated in 1979 and the years following that adept maneuvering and resolve by a strong Fed Chair could make fiat money as good as, or better than, gold. Alan Greenspan and Bernanke formalized the intuitive discipline of Volcker’s policies by elevating analytic methods of inflation targeting to the forefront. In effect, inflation targeting replaces the single commodity--gold--with a basket of commodities and other traded and consumption goods. The CPI, or more specifically CPI plus 2 percent per annum, becomes the numeraire. Bernanke’s academic works suggest that the Fed’s “dual mandate” to manage both inflation and unemployment can be optimized through inflation targeting. Countless papers on macroeconomics, modern monetary theory, and central banking, establish this as the current economic state-of-the-art, political pressures aside.

Conspiracy theories abound. The CPI calculation methodology, and modifications to it, is controversial. It is being attacked by those who think it is too subjective and those who think it is too mechanical--even though it is calculated by the BLS rather than the Fed. Turning to the Fed itself, the bureaucratic structure is complex, with ownership conceptually vested in US money center private banks, but the President of United States, and US Congress, respectively appointing Chairman and legislating its governing laws.

Ultimately, like all major US institutions, the Fed is run under an implicit license of the US government, the body politic and the country’s populace. Like all successful democratic bureaucracies, its endurance is assured by its rules and regulations and the web of interactions between these rules, regulations, practices, personnel and appointments that govern its daily operations and longer term policies.

For 99 years, this generally has worked well. Though inflation has fluctuated and crises involving gold (in 1933 and 1971), the misery index (combination of high unemployment and high inflation in the 1970s), and occasional major bank failures have come and gone, the Fed has endured. Most recently, the Fed has received high marks for doing “whatever it takes” to put a floor beneath the US economy after the bubbles in housing, banking, finance and employment imploded in 2008.

Guardian Angel

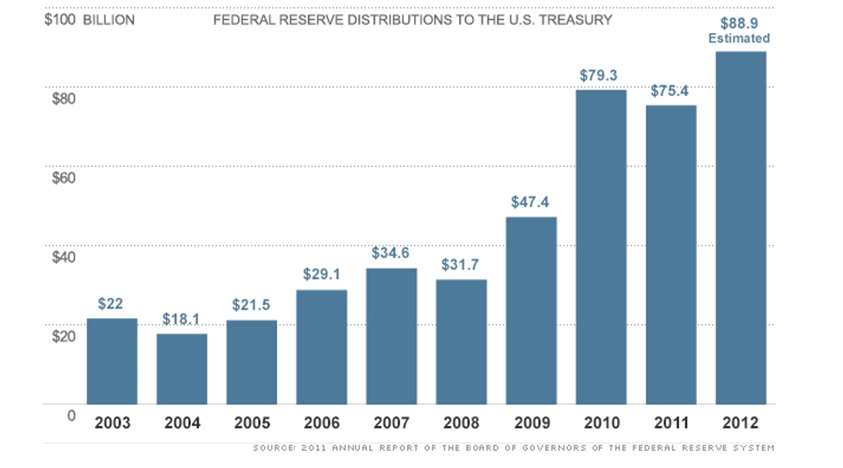

By construction a central bank’s success is generally assured. In particular, in even though the US Congress legislates aspects of the Fed’s operations, the Fed is profitable enough to both cover its administrative costs, as well as generate substantial profits, almost all of which is remitted to the US Treasury.

This profitability arises by virtue of the Fed having a monopoly position as issuer of currency. Do note that “profit” is quite different than printing money. Though many suggest that the Fed can print money (and it can), printing money merely creates Fed Balance sheet: an asset and a liability of exactly equal size. The profit comes from the difference in earning rates on assets and liabilities, less operating costs. Virtually all of the Fed’s capital therefore comes from the fraction of profits it has retained starting in 1914. This currently amounts to cumulatively $55 billion, no more, no less[2].

While demand for money, US Dollars, may seem instinctual, scholars suggest demand for officially issued money is conceptually cemented by the IRS’s authority to collect taxes. It is this demand for money that creates a positive spread between the special liabilities the Fed issues, and the generic assets the Fed owns, hence its profit.

To the extent that the Fed’s zero interest (currency in circulation) or low interest (reserves) liability is backed by higher yielding, default-free, interest-bearing assets, a profit is assured. These assets typically consist of treasury debt, agency securities, bankers’ acceptances, and a small amount of gold.

So the Fed operates a natural and legislated monopoly, and not surprisingly has been profitable every year since 1913. The profitability of the Fed, or the spread between assets and liabilities, is further assured by the perceived unlimited liquidity of the Fed. This gives it the ability to extend the duration of its assets, knowing that it can buy time during short-term panics, and somewhat appropriately use cost-based (rather than mark to market) accounting. When others are forced to sell assets, at distressed prices, the Fed can issue liabilities, and buy assets, to temporarily stem the distress. Ultimately this allows the Fed to run a modest maturity mismatch. Historically, even during times of distress, these assets have been short term in nature consisting of mostly money market instruments and Treasuries with maturities of less than 5 years. Recently, of course, this has changed dramatically.

In times of budget scrutiny (as if that is not always the case in a democracy) these profits serve as the central bank’s guardian angel, shielding it from needing to bargain for budget authority, and currying it favor, with various constituencies.

2013: the Greatest Test for the Fed, ECB, BoE, BoJ, PBOC, and SNB

Central banks often come under scrutiny. During the 1970s most notably, the Fed was often blamed for the decade-long malaise, which fundamentally was as much an outgrowth of the “guns and butter” policies of LBJ, the abandonment of the gold standard by Nixon, and vacillations of Carter, as well as a host of festering structural and economic problems. More recently a dysfunctional Congress has simultaneously had some faction berating the Fed for not doing enough of about unemployment, while others have been berating it for being too activist and accommodating. Concurrently the divided Congress decries the Fed for communicating a complicated, technical message regarding their motivation and practices, while somehow contemporaneously not providing enough transparency into their thinking and accounting. Lastly, different camps, even within the Fed, vary as to whether the Fed is too rule-based, locking itself into pre-announced policy trajectories, or not rule-based enough and too discretionary. But these challenges are perennial, and are as commonplace as the gold-bug’s call for a return to the 19th century gold standard.

The Mechanics of Central Bank Profits

Bernanke says the yield on Fed assets in excess of their costs may fall in coming years (reducing profits), but should not fall below zero. This is insanely hopeful and extremely irresponsible.

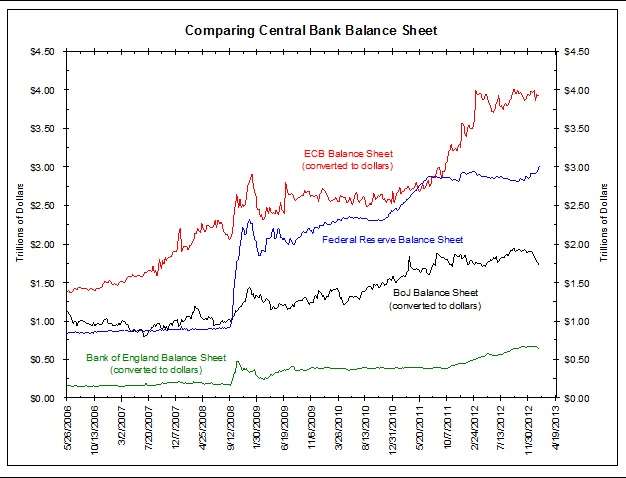

In particular, the Fed is working off an extremely thin capital base of $55 billion. Its assets consist of $3 trillion of mostly long-term treasuries. This means the Fed is operating on a leverage ratio of 54.54 times, ignoring any off-balance sheet obligations. The use of staff “base case” trajectories for interest rates and yields as the basis for this type of risk analysis on a highly levered portfolio is deeply flawed.

Fed assets yield an average of 2 ½ percent, while the 10-year TIPS inflation break evens are 2.52% and the 30-Year TIPS inflation break evens are 2.54% suggesting that the market is pricing in an average inflation over a long term time horizon of 2.53%. So Bernanke’s projections of profitability implicitly, therefore, assume a negative real Fed Funds rate for the next 10 to 30 years.

If one were to assume a zero real Fed funds rate, the Fed would earn a profit equal to the negative real interest rates received by holders of less than $1 trillion of currency in circulation, or about $25 billion a year if inflation averaged 2.5%. This is less than ¼ of its recent rate of the estimated $90 billion remitted to Treasury in 2012. (This $65 billion decline would of course need to be made up by Congress, as reduce revenues for the US Government would exacerbate current budget woes.)

If one were to add the typical 2% real Fed funds rate (the average over the past 50 years and the rate suggested by the Taylor rule needed to target inflation in a well-functioning economy) to this inflation rate as a forecast of the average Fed Funds rate over this horizon, the earnings spread on the Treasury Balance sheet, ignoring any operating costs, would amount to -2% per annum on more than $2 trillion of assets, not backing currency in circulation. This would result in loss of more than $15 billion per annum for the next 20 years, and a present value of $300 billion dollars or worse. This would wipe out the Fed’s current total capital of $55 billion five times over. This is reminiscent of the unsophisticated homeowner who financed long term housing assets, with ARMs, during 2004-2007, and of similar magnitude to the Freddie and Fannie debacle.

Fed accountants, according to recently announced changes, would not report this as negative capital. Instead they would create an asset, unheard of outside Fed accounting circles, which I’ll paraphrase as “anticipated future earnings not remitted to the Treasury.” The negative optics of this negative present value would of course be exacerbated if the Fed were to fight inflation by shrinking its balance sheet.

Of course, things may play out much worse than a base case scenario. Since all these inflation rates, and interest rates pivot off demand for dollars, a fall in demand for dollars could increase the cost of funding the Fed assets. In addition, attempts to sell Fed assets (to stem a decline in the exchange value of the dollar) could cause yields to spike, exacerbating optics of the negative capital position of the Fed balance sheet, due to its effect on both long term bonds held as Fed assets and cost of Fed liabilities funding those assets.

Adding to the fragility of the system are the US government budget woes. Though the US Treasury is trying to extend the maturity of its financing arrangements towards 84 months, currently half of the US Treasury debt held by the public is scheduled to mature in 36 months and will need to be rolled over. Should international investors, including those with natural resources and low labor costs at home begin to eschew the US dollar, perhaps in favor of hard assets, precious metals, or income producing assets in resource rich emerging nations, a fall in the dollar (and the currencies of other developed world nations) would tend to drive up commodity prices, natural resource prices, and inflation more generally, exacerbating the Fed’s insolvency.

Global Central Banks

Other central banks may be in as bad or worse conditions than the Fed. Looking just (figure below) at the size of the assets, we can see they have all been rapidly expanding since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. In the case of the Fed, assets have grown by over 300%, from 800 billion dollars to now 3 trillion dollars.

Source: Bianco

The ECB maintains huge exposure to periphery Europe. Absent military excursions by the ECB (which does not have a standing army), European monetary policy is, however, essentially at the whim of local populations. Populations in the core—primarily Germany--are tired of funding the periphery; and local populations in the periphery are tired of externally imposed austerity. Recall, as my childhood congressman Tip O’Neal quipped, “All politics is local.”

The most explicit manifestation of this ECB imbalance is Target2 liabilities, in the range of 700 Billion Euros (1 T$). These are liabilities of the ECB, which reside as an asset on the Bundesbank (the national central bank of Germany) balance sheet. In turn the Bundesbank uses these to back deposits in the German banking system. This asset is essentially a pool of unsecured loans on periphery real estate of questionable ultimate value channeled through a chain consisting of local periphery banks, periphery national central banks, the ECB to ultimately the Bundesbank.

With the UK being downgraded, the flexibility of the Bank of England is limited. Though it has been 20 years since the Pound was challenged, all readers are familiar with the current inherent conflict between austerity and growth that the UK and developed countries face. The UK is now once again facing a dilemma, both a recession and inflationary pressures. Where is Alexander the Great when we need him?

The Bank of Japan, by virtue of its December election of a new government, recently embarked upon installation of a new central banking regime, which has a mandate to reflate. This goes along with raising the targeted inflation rate to 2% from 1%, and thereby realize inflation rate from its flat-line two-decade average of just more than 0%. It will presumably do this through expanding and extending its asset purchase program from already high levels. The dramatic inflation in import and raw material prices is already creating a backlash against this policy by both consumers who are seeing their budgets squeezed, and domestically focused companies, who are seeing their margins squeezed. (Japanese companies that export and their employees, of course, are the main beneficiary of this policy.)

Lastly the China’s PBOC and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) are also the focus of international investors. In the former case, questions regarding extreme levels of leverage at the provincial level, and within the real estate sector are balanced against stronger fundamentals at the level of national balance sheet and vast economic resources (primarily a huge, low-cost, highly skilled and growing labor force). In the case of the SNB, recent efforts to reflate the Swiss Franc, by putting a floor on the EURCHF exchange rate at 1.20 has resulted in the thin capital base of the SNB being levered to extreme levels by the purchase of euro denominated Bunds, and other international assets, which fluctuate wildly in price.

Epilogue

These are the “the known knowns.” There are of course many “known unknowns.” But most importantly, one must also take Donald Rumsfeld’s advice to heart, “there are also unknown unknowns,” which every trader knows are the most perilous.

Going forward, I am hopeful and confident. We have made much headway since 2008, taking a complete meltdown of the global economic system off the table. In recent weeks, gold has traded down (meaning the dollar and most currencies have traded up relative to gold) reflecting reduced tail risk. Tail risk has two sides—deflationary and inflationary. Gold is suggesting that the risk of a deflationary financial Armageddon (in which gold would likely be highly sought after), and the risk of double-digit inflation or more extreme hyperinflation (in which gold would also be highly sought after) have lessened.

Though Bernanke and the Fed dismiss the challenges of an exit strategy, we know they are not entirely ignorant that there will be some costs and challenges. Likewise, in Washington the debate between budget balance and stimulus, is vibrant and active, with neither side advocating either nominal cuts in spending, nor real growth in spending.

[1] Mr. Brynjolfsson oversees all investment activity at Armored Wolf. He is an expert in the area of managing alternative real assets; and his experience includes commodities, global inflation-linked bonds, event-linked catastrophe bonds, asset allocation and risk management.

A popular and provocative communicator, Mr. Brynjolfsson is a frequent guest on Bloomberg TV; has been quoted in The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal and featured in Fortune; is a member of industry advisory committees; and has testified before the House Financial Services Committee as an expert on catastrophic risk transfer.

Mr. Brynjolfsson is co-author of Inflation-Protection Bonds and co-editor of The Handbook of Inflation-Indexed Bonds. He has 23 years of investment experience and holds a bachelor’s degree in physics and mathematics from Columbia College and a master’s degree in finance and economics from the MIT Sloan School of Management.

[2] From recent FRB financial statements, rounded. Of course, due to Fed accounting practices, the “real” capital may be smaller, or larger given for example unrealized mark-to-market gains in value of gold holdings recorded at cost.