East Asian pension systems face an on-rushing demographic crunch, compounded by certain long-venerated characteristics of the East Asian development model.

East Asian pension systems face an on-rushing demographic crunch, compounded by certain long-venerated characteristics of the East Asian development model.

Business schools and popular books on economics have taught for decades that the West ought to open itself and learn from the successes of the distinctive Asian style of capitalism.

There may be much to learn indeed, but a new EDHEC report, “Investment Solutions for East Asia’s Pension Savings,” suggests that it won’t all be positive.

Definitions

The definition of East Asia for purposes of this study includes: Japan, Korea, Taiwan, mainland China, and Hong Kong. The retired portion of the population there is getting larger and, since fertility remains below the levels that would be necessary to replace retiring workers with new workers, the over-all ageing of the population will continue for years to come.

Considered abstractly, one can address such issues by increasing the level of workers’ savings, or by increasing the effectiveness with which those savings are invested for use during retirement. Yet in the concrete circumstances of East Asia, savings rates have long been high, and cannot plausibly be expected to get much higher. Indeed, they may be in certain respects too high, as we’ll see. Thus, as the EDHEC report observes, “most progress has to be made on the asset management side.”

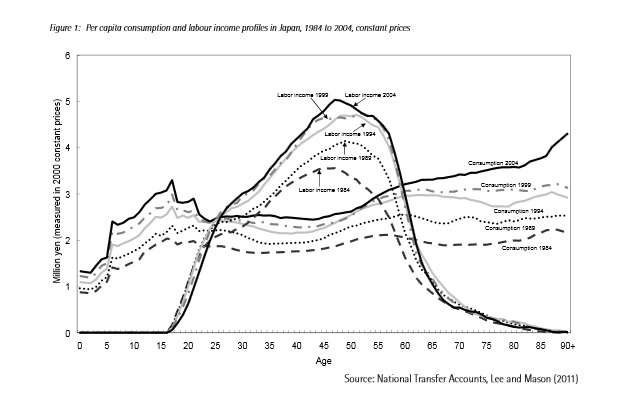

The graph below shows the demographic crunch specific to Japan. The X axis in this graph represents the ages of members of the population. The large lop-sided bell in the middle of the graph represents average labor income year by year. Japanese earners, as you can see, hit their highest earnings level in their late 40s.

You can also see that the level of the central portion of that bell has been raised over time. The lowest of the bell-shaped lines represents labor income in 1984. The highest represents labor income in 2004. [This is income in real, not nominal figures.]

Ignore the left-hand side of this graph for a moment, because that represents expenditures for the benefit of growing children, which suggests an intergenerational transfer. The middle and right-hand sides of the graph suggest an intra-generational transfer. As a first approximation one may say that in a sustainable system, the income from one’s working years will support the consumption of one’s retirement years. In graphic terms, the bubble in the middle (the positive difference between labor income and consumption in those years) will be equal to or larger in area than its inversion at the right-hand side (the negative difference between labor income and consumption).

If the area of the bubble is too small, the difference may be made up by the investment earnings of the saved portion of that income.

Consumption has been increasing in real terms too, though, as another set of lines on this chart tells you. Further, the consumption 2004 lines tell us that by that year the rate at which a Japanese individual could be expected to use money was increasing throughout the retirement years. After the income and consumption lines cross, the consumption line heads steadily (though for the most part slowly) upward.

The East Asian Model

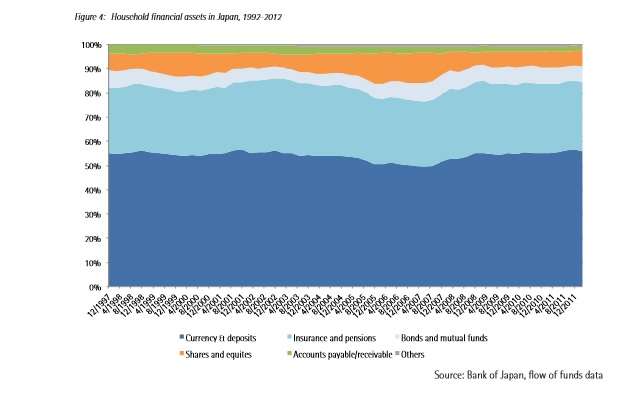

To look in another way at the level of savings, note the graph below. This works from flow of funds data from the Bank of Japan, and indicates the nature of household assets in that country, from 1992 to 2012.

This confirms our earlier point, that is, that there can’t be any very realistic expectation that the amount of savings will increase. The habits of Japanese householders are rather reliable – these bands all seem to stay of a constant thickness over the decades. The light-blue band (second from the bottom), representing each household’s insurance and pension assets, represented about 25% of the whole in 1987 and it still represents 25% of the whole to this day.

So the challenge created by a demographic crunch is one of wiser investing: getting more out of that 25%. The challenge is heightened by the economic fundamentals of the region. As EDHEC notes, the so-called East Asian model of economic development has created “a number of structural financial distortions.” In particular, this model often involves the maintenance of below-equilibrium interest rates, especially when they are considered in real terms. This is a system – sometimes called “financial repression,” – that taxes savers and subsidizes borrowers.

This is thought to assist development in that it lightens the debt load on firms with privileged access to credit. EDHEC politely calls these firms the “state-sponsored sector,” although less polite folks might use the term “cronies.”

This has important consequences: most obviously, it makes the return on cash and fixed-income securities very low. It even makes the real return negative. Note in the figure above that somewhat more than half of household assets in Japan are held in currency and deposits (the bottom tier). In urban financial households in China in 2012 cash constituted 18% of the whole, bank savings 59%.

Consequences

Somewhat counter-intuitively, households increase their savings (reducing their consumption) when savings are so drastically unremunerated. This is because households have a “target savings level” in mind – for example, the sum needed to buy their next car – and as the interest rates on their deposits go down, the amount of money they need to put away to reach that target increases.

These excess household savings, EDHEC says, “imply a dynamically inefficient economy [with] direct implications for asset allocation.”

Part of the answer, at least for Hong Kong and Taiwan, may lie in attracting workers from outside. Those two jurisdictions are in a position to accommodate immigration. Others are not, which makes “ongoing and accelerating population ageing a much more urgent and unavoidable problem.”

So: what’s the broader solution? EDHEC suggests the introduction of scientific investment concepts, such as liability-driven investment or life cycle investment, in the methods of pension savings plans in the region. This requires “fundamental changes in the way reserve funds have been controlled and managed for the past decades, and … investment management processes and tools that will allow pension reserves to achieve what should be their sole objective,” ensuring adequate provision for the retirees, present and to come.