Private equity, when investing in privately offered funds, is a highly complex and complicated asset class. Minimum investments are typically extremely high, and often the best fund managers are oversubscribed and not offered to investors that did not invest in their previous fund. Further, it is extremely important for investors seeking access from the perspective of taking advantage of the favorable, return enhancement characteristics of privately offered private equity funds to select one to two handfuls of private equity funds to commit to, as over-diversification could lead to diminished returns and eliminate the benefits sought by investing in these funds to begin with. Here I will discuss some of the most common complications related to accessing private equity, managing a private equity portfolio, and managing/minimizing risk in a private equity portfolio.

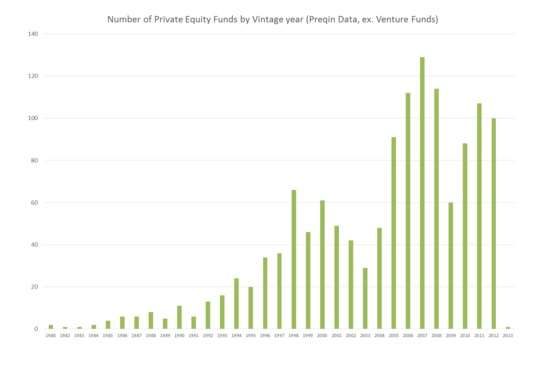

Private equity has nonetheless grown significantly in popularity, among both investors and among asset managers launching funds to take advantage of the demand for private equity investment opportunities. Prior to the 1980s, and truly into the 1990s, most private equity deals were “Country Club” deals conducted by a tight group of friends or colleagues as closed, non-offered investment partnership. However as can be seen below, according to Preqin, the premier private equity investment research firm in the US, Private Equity Funds have gone from virtually a handful in the early 80s to over 120 in the middle part of the first decade of the 21st century.

Investors may think, given the growth in popularity and the number of funds offered, it couldn’t be too complicated, could it? It is. The benefit of this complexity is that typically, the best managers generate returns that are in excess of the public equities by 400-800 basis points on average, per year, over the life of the fund(s). Complexity, combined with the inherent illiquidity of making a private investment offer what have come to be known as private equity risk premiums. The return enhancement characteristics of private equity are not easily accessed though.

The first, and most common complication found when investors attempt to gain access to private equity is that typically, private equity funds and their managers are hard to predict, and often the investor must wait for the manager to approach them with a new offering. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the best managers are often over-subscribed in follow-on funds and do not accept new investors making it close to impossible to start your private equity program with the best of breed managers, subsequently placing your capital commitment in the hands of less experience, less known managers, that do not have a previous track record of success. If you happen to stumble across an offering from a well known manager with previous success and a high degree of persistence, it is likely that the manager will be offering the fund at extremely high minimums. This makes investing in these funds realistic only to the largest, most well-capitalized institutional investors such as endowments and pension funds.

Hypothetically however, let's assume you have found one of the best of breed private equity managers launching a follow on fund. Now the question is how much do you commit, and what do you do while waiting for the manager to call committed capital. Private Equity funds are offered sporadically, when the manager feels fit, and are typically compared to funds offered the same year. The year a fund is offered is referred to as the vintage year, and carries the same meaning as a vintage year in wine. With fine wine, though the fund may be a vintage year 2005, it may not be drinkable for another 2-3 years. This actually has more in common with private equity funds than a lot of investors may desire. When committed to a 2005 vintage year private equity fund, it may be a year or two before the manager calls any capital from your commitment. Further, it may be 4-5 years before the investor has called all of the capital, if the manager ever calls all of the committed capital. Often private equity managers only call the capital needed, and as investment opportunities and valuations change, private equity managers may decide their fund is better off sticking to its current portfolio and focusing on generating value from existing investments rather than calling additional capital. Management fees are typically paid on the total committed capital, not the called capital leading to complications and often complaints from investors who feel they are being ripped off by managers that have not deployed the capital they have committed. If the manager does not call all of the committed capital, investors are left with performance on a smaller allocation than anticipated, leaving the additional, uncalled capital in low risk, high liquidity investments that typically display lackluster returns.

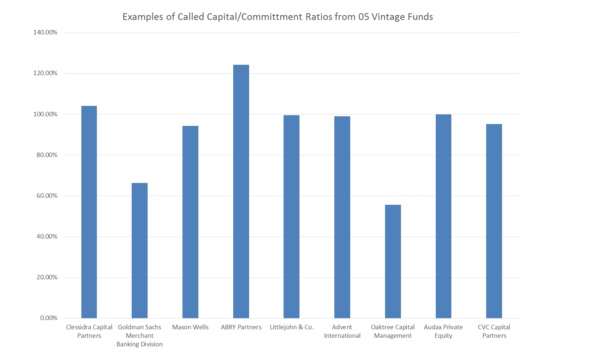

This has led sophisticated investors to employ an over-commitment strategy when investing in private equity, however there are many complication and issues that face the over-committed investor. The first being already mentioned, is fees. Over-commitment means the investor will pay fees on a higher allocation than the investor expects to receive returns on. The second complication relates to liquidity. What happens if the manager does call all of the committed capital? Typically it would lead to a liquidity crunch and a necessary fire sale of other assets, as well as an over allocation to private equity. The third complication related to an over commitment ratio is performance measurement at the investors private equity portfolio level. As mentioned earlier if the manager of the private equity fund does not call all the committed capital, investors are typically left with diminished returns, as the remainder of the committed capital sits in investments such as treasury bonds. Investors are faced with these decisions when implementing an over-commitment strategy. Over-commitments can be significant. According to the CAIA Association, over-commitments of 140% and greater have been observed, and according to a statistical model found in the white-paper by Pinebridge investments titled “Achieving Private Equity Allocations Targets: Eliminating the Guesswork”, an investor building a new private equity allocation program may need to over-commit an astounding 240% of their target allocation in early years. Below is a chart showing the called capital from 9 select private equity funds from the 2005 vintage year.

I mention the best-of-breed managers, as there is a lot of research finding that top performing private equity funds tend to perform in the top quartile for follow on funds. Unfortunately this is not a given, and this is not a “fund after fund after fund” characteristic (According to Chung, 2010). Typically, this persistence only relates to the next fund offered, and only relates to about 37% of private equity managers (according to a white paper written in 2010 by Ji-Woong Chung titled Performance Persistence in Private Equity Funds) whom have a top performing first fund. 37% is high enough for statisticians to consider it statistically significant persistence, but anybody who tells you that they could select the 37% of funds that performed top quartile in their previous fund should be playing blackjack in Vegas, they are a psychic. It is virtually impossible to have enough insight to select only managers that will again perform in the top quartile, given that 73% of the fund managers who perform at the top of their vintage year will not perform at the top of their vintage year with follow on funds. 37% may be statistically significant when studying epidemics, but not when selecting private equity funds. Further, when fund managers launch their follow on fund, it is typically right after they have finished calling down committed capital, and have yet to generate any positive return. The reason for this brings us to our next complication, which is one of timing cash flows, and remaining patient through the private equity J-Curve.

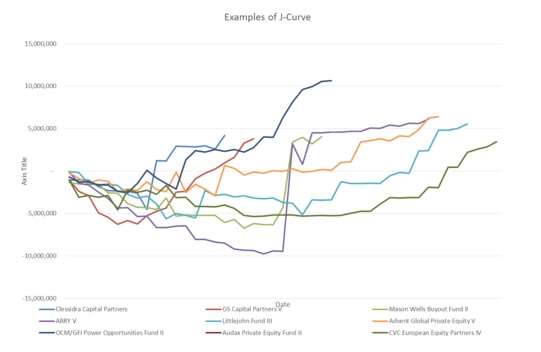

Above is a chart showing the vast differences of the J-Curves that could be observed when investing in private equity funds. Using the same 9 funds from the 05 vintage year that were used to show called to committed capital ratios above the previous paragraph, investors can clearly see that private equity funds, during the capital calling cycle experience significant drawdowns in their commitments before cash flow distributions begin. The above chart shows selected profitable 05 vintage year funds, however many private equity funds in the worst quartile for any given vintage year generate significant capital losses and do not even distribute enough cash flow from underlying investment income to cover the capital committed by the investor. Further, for those that are profitable, it may be many years before the distributions overcome the called capital, leading the investor to need an overwhelming amount of patience with, and trust in expertise of the manager.

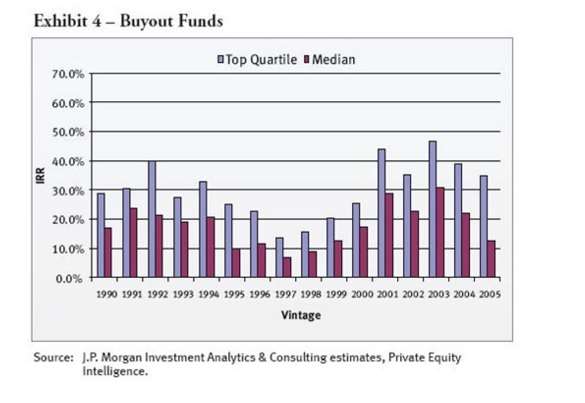

Back to the topic of top performing private equity funds, investors in private equity know that it is extremely important to select only a handful of expected top quartile funds, and essentially hope they perform as expected over the long life of the fund (often 7-13 years). According to JP Morgan, when measured by IRR (a common but flawed performance measurement for private equity), investors witness a severe divergence between top quartile and median performers in the private equity space. Often as high as 20% for given vintage years. Average divergence has been cited at 8% per year and as high as 16% per year, based on the year of the study and depth of data. Therefore in order to generate the return enhancing qualities of private equity investors must essentially carry psychic powers to be able to select only the top performing managers, 10 years before their performance is even known, and the only true expectation measurement is the previous fund managed by that manager, which may only be 3 or 4 years old. Even then, as mentioned earlier, only approximately 37% of follow on funds launched by top quartile private equity manager will generate top quartile results. Below is a chart from JP Morgan Investment Analytics & Consulting comparing the top quartile performance (IRR) for a given vintage year to the median performance for that same vintage year. The chart says it all.

Further complications relate, again, to the illiquidity of private equity. Due to its highly illiquid nature, there are very few, if any options for minimizing and managing risk as a standalone investment and as a part of a private equity portfolio. According to the CAIA Association there are essentially 7 highly inefficient ways to manage risk and liquidity once invested in a private equity fund.

1. Follow-on Funding: The first way to manage risk and liquidity is out of the hands of the investor (limited partner) in the private equity fund, and relies on the fund manager seeking follow on funding if the limited partner capital commitments exceed the cash flow generated by the private equity fund. This essentially leads to a longer life of the fund, and a longer wait time before investors experience returns, assuming the follow on funding is invested efficiently and able to capitalize on later investments.

2. Liquidity Lines: Likely only available to the most sophisticated, largest investors with the longest time-frames, or to the private equity manager. Using short term or long term borrowing facilities may generate additional liquidity, but it also generates additional risk, and while leverage may enhance returns to the upside, it can also be devastating on the downside, possibly leading to total losses for the limited partner.

3. Maturing Treasury Investments: Investors in private equity funds often over-commit to the funds they are investing in, as discussed earlier. The uncalled capital remains in liquid, low risk investments and may provide a source of additional funding, if needed, to the private equity funds that are struggling.

4. Realizations of Investment Returns: Private equity managers may utilize returns from some investments to either subsidize losses in others, or continue to fund investments that burned more cash than expected but still may generate returns.

5. Selling Limited Partnership Shares: In extreme cases, if liquidity is needed immediately, or if the LP no longer trusts the manager to perform years into the fund’s life, investors may, in some cases, with the permission of the manager, sell their shares in the fund through private secondary offerings. Often, secondary private equity fund offerings trade at a significant discount to expected future value, and typically lead to significant losses for the investor.

6. Previous distributions: If the investor has already received distributions from the private equity fund, or expects additional distributions in the near future this may be a source of liquidity. Further distributions from well performing funds may subsidize losses from funds that are performing poorly.

7. Investor Default: If the investor no longer trusts the manager to make sound investments that will perform as expected, the investor may have to take a drastic step and not approve additional capital calls. This will lead to the investor defaulting on their commitment and could have legal ramifications, however in extreme cases, it may be necessary to cut the poor performing manager off. Often this will also mean that the investor is banned from follow-on fund offerings by the same manager, and if word spreads, may lead to “blacklisting” of the investor among many private equity managers, even those competing with the fund defaulted upon.

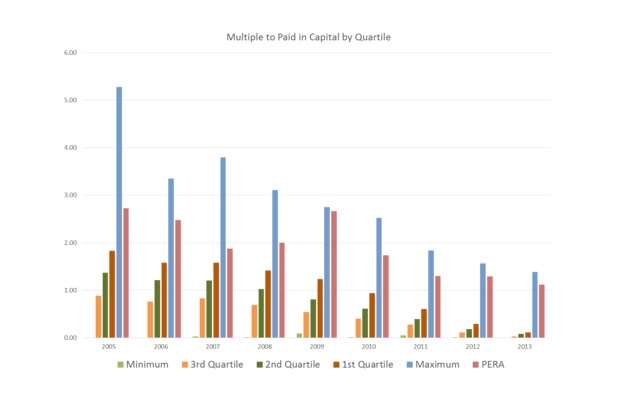

The final complication we will discuss relates to performance measurement in private equity. As mentioned above, the traditional measure of performance for private equity is the Internal Rate of Return or IRR. IRR is the discount rate the equates the net present value (NPV) of an investment to 0. IRR is calculated using either a business calculator or a spreadsheet. IRR has many flaws including its compatibility with many other investments in a diversified portfolio. Most investments, traditional and alternative have their performance measured using a compound annual growth rate. In order to compare private equity to other investments it is often necessary to create a “Public Market Equivalent” analysis in which the cash flows of private equity are matched up against an index value and the index the private equity investment is being compared to has its performance converted to an IRR by assuming entry and exits are on the same date as calls and distributions. This method can be complicated, and still carries a significant flaw. IRR assumes all capital is able to be reinvested at the IRR. Since this is highly unlikely, many private equity investors use a Modified-IRR, which may be more accurate taking into account a pre-specified and assumed achievable reinvestment rate. This can still carry the flaw of misassumption of the reinvestment rate. At NMMacro, we believe a more accurate measure of performance for private equity, and much more comparable performance measurement when comparing investment options is the Multiple to Paid in Capital (MPIC), sometimes referred to as multiple return. Multiple return is a total return measurement that takes into account the called capital and divides the total cumulative distribution by the called capital. This metric, once calculated can become even more comparable to other investment options by converting it to a compound annual growth rate by raising the MPIC to the power of (1/life of fund in years). Below are a chart of the MPIC of Private Equity Funds, Vintage Years 05-13 and CAGR for Vintage Years 05-08 (later years eliminated due to funds of all quartiles still being in the J-Curve part of the private equity fund life cycle), respectively.

Investors have to ask themselves, is there a better way to gain exposure to private equity?

The answer is an astounding yes! The NMMacro PERA Index is a better way, and has proven so over the past 9 years. Private Equity has evolved significantly since the 1990s. In the 1990s if an investor wanted less complicated, more comparable (to public equities) exposure to private equity investments they had to invest in the Private Equity Managers that were publicly traded. Managers however, depending on their fee structure (which varies significantly from fund to fund), typically have not performed with a close correlation to the performance of the private equity funds they manage. Over the past 2 decades however, loosening in regulations have led to new publicly offered structures for Private Equity Funds. These structures are called Business Development Companies, and they have performed, not only similar to private equity funds, but when selected by rigorously applying the NMMacro PERA Index methodology (designed by a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst utilizing special skills to analyze the BDC market, and built to mimic top performing privately offered private equity funds), they have astoundingly mimicked, and outperformed top quartile privately offered private equity managers. As can be seen in the first chart above, unless investors are able to select the 1 best privately offered private equity fund from a given vintage year, which is virtually impossible to know when the fund launches, investors would be far better off investing in the PERA index, benefiting not only from the performance enhancing characteristics of the private equity funds, but also the liquidity of public markets, and much greater diversification, without needing the patience to deal with the sometimes extended J-Curve part of the privately offered private equity fund life cycle.

Investors seeking to gain access to private equity should consider the PERA Index as their first option. The cost efficiency, the liquidity, the inherent diversification, and the out-perfomance of top quartile privately offered private equity funds speak for themselves.

Andrew N. Smith, CAIA is a Co-Founder and Chief Product Strategist for OWLshares and serves as the chairperson of the Steering Committee for the Los Angeles Chapter of the CAIA Association.