By Charles Skorina

By Charles Skorina

In July, Scott Evans reported for duty as Chief Investment Officer in New York City's Bureau of Asset Management, where he'll manage $160 billion in employee pension funds.

Traditionally the city's CIO is replaced when the political wheel turns, which it did last fall.

Retiring Mayor Michael Bloomberg was succeeded by William De Blasio; and Comptroller John Liu, the independently-elected custodian of the city's pension funds, was replaced by Scott Stringer.

Mr. Stringer beat back a last-minute primary challenge from disgraced former Governor Elliot Spitzer (known to New York Post readers as "Client No. 9 "), prevailing by 52- to-48.

We have to admit that we rooted for Mr. Spitzer, hoping that he would generate more colorful stories for us. Alas, we are now stuck with the colorless and (so far) untainted Mr. Stringer.

Following the election, former CIO Lawrence Schloss resigned after four years on the job, moving to asset manager Angelo, Gordon & Co. as their new president. Mr. Evans' appointment was announced a few months later.

The New York CIO job pays about $224 thousand, which is pretty good for a city employee, and pretty lousy for an equivalent position on Wall Street.

Mr. Evans earned an MBA from Kellogg/Northwestern in 1985 and went to work in New York as an equity analyst for TIAA-CREF. For twenty-seven years he worked his way up through the ranks, finally serving as TIAA-CREF's EVP and President of Asset Management before retiring in 2012.

Even between day jobs, Mr. Evans has kept busy. He's on the investment committee of Tufts University (his undergrad school), and on the board at W.T. Grant Foundation. He's also an advisor to the $300 billion Dutch mega-fund Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds (ABP).

It's a solid resume, but now Mr. Evans will have to deal with the bare-knuckle politics of New York City, which may prove to be somewhat different from managing annuities for college professors.

We could also point out that the underlying investments for TIAA-CREF's retirement products and retail mutual funds are almost exclusively public equities and fixed income. So, Mr. Evans' hands-on experience with alternatives seems to be limited.

Although the CIO tries to manage the city's five public pension funds as an aggregate, each fund has its own board, dominated by its respective union. Technically, he can only "advise" the five boards, each of which can, and sometimes does, try to micro-manage investment decisions.

The comptroller (or his deputy, usually the CIO), sits on each board; but so does the Mayor (or his representative). In an effort to increase his leverage over pension management, Mayor Bloomberg created a sort of mini-CIO, a "chief investment advisor."

Ranji Nagaswami was hired as the mayor's first CIA with considerable fanfare in 2010, but she left after two years for a job with Ray Dalio's Bridgewater hedge fund. She was succeeded by Janice Emery in 2012.

Last month Ms. Emery left the Mayor's office to take a job as endowment CIO for the American University of Cairo (conveniently located on New York's Fifth Avenue, rather than in Egypt). It's not clear whether Mayor De Blasio will replace her as his CIA, or with whom.

Four years ago Mayor Bloomberg and Comptroller Liu promised a joint effort to streamline the five-headed pension system.

The five boards with their 50 trustees were to be squashed into a single 12-member body that would set investment policy. The CIO's office would then have been separated from the comptroller's office to insulate it from politics. This setup was deliberately patterned after Canadian plans like Ontario Teachers' Pension (see our piece about Gordon Fyfe and the Canadian pensions further below).

But, as a spokesman for Mayor Bloomberg said: "The plan was cut off at the knees by some of the unions."

A good New York Times article last month dissected the politics of the city's pension system in some depth.

NYC Pensions by the numbers:

Taken as a single fund, the NYC pension system now has a total AUM of about $160 billion. That makes it the fourth-largest public pension fund in the U.S, and one of only six with assets over $100 billion.

Leaving aside their apparently intractable governance issues, how did the NYC system perform under former CIO Lawrence Schloss? And what challenges face incoming CIO Scott Evans?

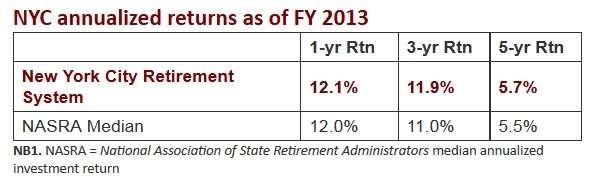

As the little table below says, the annualized return for the five fiscal years 2009-2013 was about 5.7 percent and the three-year return for 2011-2013 was 11.9 percent.

On this basis, recent NYC performance is slightly above the median.

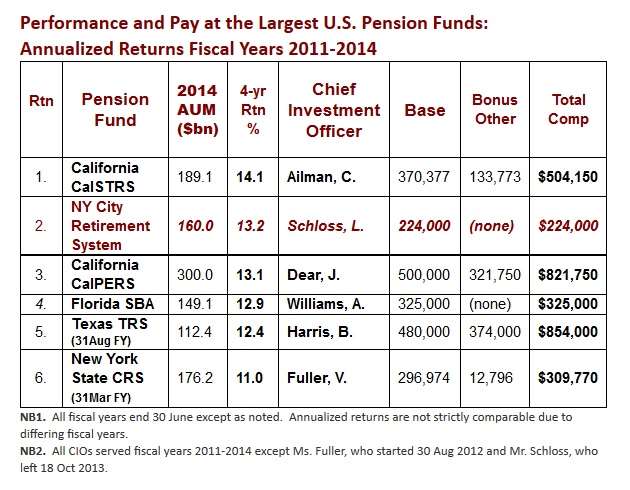

We can zoom in a little tighter on performance in Mr. Schloss' tenure and compare it directly to NYC's closest peers.

He took office in January 2010, so fiscal year 2011 is the first period he could influence at all. And, although he left last fall, he should properly get the credit (or blame) for the latest fiscal year ending June 30, 2014.

Here are results for that four-year window -- 2011 to 2014 -- for NYC and its closest peers:

NYC had the second-highest 4-year return among their peers. They finished behind CalSTRS and a hair ahead of the much bigger CalPERS.

But Mr. Schloss had the lowest comp by far. Britt Harris' bonus alone in 2013 was larger than the total comp paid in New York City, and Mr. Schloss was presiding over a larger fund with higher returns in this period.

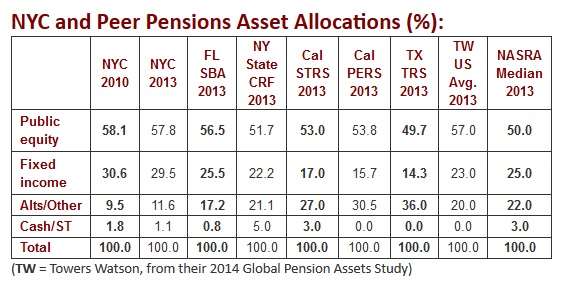

Now, what did their allocations look like compared to their peers?

Over the four years 2010-2013 Mr. Schloss increased NYC's allocation to alternatives by a little over 2 percent of AUM, carving it out of public markets and cash. And most of that net increase was in hedge funds, starting with essentially zero HF exposure in 2010.

But an 11.6 percent exposure to alts in 2013 still left NYC on the low end of the spectrum compared to the other mega-funds and to the average U.S. pension.

On this chart, allocation to alternatives increases from left to right across the six peer funds.

Although the alts allocation increased significantly on Mr. Schloss' watch, it was still lowest by far among the six peers, and well below the national mean and median, which include funds of all sizes. If NYC's allocations to alternatives were lower, then obviously exposure to traditional public-market assets had to be higher, and we see that that was the case.

NYC, then, had the most traditional-looking portfolio in this group. If we think of this as a long march toward the endowment model, then NYC is bringing up the rear.

But, as we saw above, that more-traditional allocation has worked well for NYC, at least in this recent period when stocks were booming.

Mr. Schloss got his MBA from Wharton and spent 22 years managing alternative assets at Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. When DLJ was acquired by Credit Suisse First Boston he became global head of CSFB Private Equity with $32 billion AUM. In 2004 he left Credit Suisse to found his own private equity firm, Diamond Castle Holdings.

Given his background in private equity, we wondered if anything interesting happened in that bucket during his tour with the city pension fund.

Total dollar commitments to PE were up about 70 percent over four years 2010-2013, from $10 billion to $17 billion, but actual investments were up only about 40 percent, from $6.1 billion to $8.1 billion, just keeping pace with the growth of the whole portfolio and a rising stock market. The difference is an accumulation of "dry powder" which the GPs will invest on their own schedule.

NYC's PE investments were spread over 182 partnerships run by 109 different managers as of 2013. Neither of those numbers seems to have changed much over five years.

Among the largest public pensions, NYC's allocation to private equity has been on the low side. Their actual allocation in 2013 was 6.3 percent. That number barely budged over four years, although the dollars invested rose more than 40 percent along with total AUM: from $6.1 to $8.7 billion.

The slightly larger CalSTRS, for instance, had about twice as much PE: 13.2 percent in 2013, and Texas TRS had 12.3 percent. A few other major pensions, including Washington SIB, Oregon PERS and Pennsylvania PSERS allocated over 20 percent to private equity in 2013.

Charles A. Skorina & Co is retained by the boards of institutional investors and asset managers to recruit chief investment officers, portfolio managers, and financial professionals.

Charles Skorina earned an MBA at the University of Chicago and began his professional career at Chemical Bank (now JPMorgan Chase), completing the management training program then working as a credit and risk analyst in New York and Chicago. After a stint with Ernst & Young in Washington, D.C., he founded his own search firm headquartered in San Francisco, focused on the global financial services industry.