Ah, the mid 1990s. Memories. The Soviet Union was no more, and fashionable academics were writing books about how the world had reached the “end of history,” a time when the old ideological disputes would fade away, because everybody now understood that multi-party republics and capitalistic economic systems [with softened social-democratic edges] were the way to go. Policy wonks translated this vision into the “Washington Consensus,” a set of rules for how underdeveloped or war-torn countries could develop and join the club of the peaceful and developed.

Ah, the mid 1990s. Memories. The Soviet Union was no more, and fashionable academics were writing books about how the world had reached the “end of history,” a time when the old ideological disputes would fade away, because everybody now understood that multi-party republics and capitalistic economic systems [with softened social-democratic edges] were the way to go. Policy wonks translated this vision into the “Washington Consensus,” a set of rules for how underdeveloped or war-torn countries could develop and join the club of the peaceful and developed.

Boris Yeltsin, the flawed founder of post-Soviet Russian politics and a man with a flair for the dramatic, was Russia’s president; a smooth path to the privatization of the high plateaus of the post-Soviet economy was surely possible; and opportunities for foreign investors were everywhere.

Hermitage Capital

William Browder entered this scene, and entered into such rosy scenarios, in a big way, as CEO of the activist Hermitage Capital Management, the firm he founded in 1996, with help from Edmond Safra. Through the nine years after the founding of Hermitage, Browder profited handsomely, earning by one estimate roughly $140 million a year at his peak. Under his leadership, too, Hermitage grew to such an extent that, nine years after its founding it had $4.5 billion in assets under management.

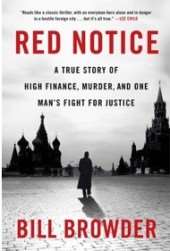

Browder has now written a book, Red Notice, about his rise to prominence as a leader of the wave of foreign investment in Russia under first Yeltsin, later Putin. And about what happened next, when the relationship between those investors and Putin turned very sour. The easy summary: it is all very well to pursue alpha in frontier circumstances, but it is not for the faint of heart.

Part of the fascination of this story comes from Browder’s own lineage. His paternal grandfather, Earl Browder, chaired the Communist Party USA from 1934 to 1945, loyally taking orders from Stalin both when Stalin was allied with Hitler and when the tables turned, and Moscow had to tie its fate to that of the western allies.

Earl’s son, and William Browder’s father, is the renowned mathematician Felix Browder, a professor at Rutgers University and an authority on “topological fixed point theory.” [No, I don’t know what that means.] One would not a priori have expected Earl Browder’s grandson to be so enthusiastic and successful a hedge fund manager. But if one had made that guess, one would probably have expected that the son of Felix Browder would focus on some quantitative, algorithmic system in the hunt for alpha. Instead, William Browder sought gains for himself and his investors through qualitative research and all-too-human judgment calls.

Sidanco

He was in the business of looking for undervalued companies, especially in cases where the undervaluation resulted from the under-exposed nature of the assets: diamonds in the rough.

This worked well with Sidanco, which was first described to Browder in a conversation in August 1996 as “a big oil company in western Siberia that no one’s heard of.” It was effectively controlled [96% owned] by an investment group led by Vladimir Potanin, who by coincidence was then the deputy prime minister of Russia.

Accurate information about Sidanco turned out to be hard to find, because only 4% of the company’s equity was available for sale on the market, so as Browder writes the sliver of public equity wasn’t enough “to compel any analyst to waste time writing research reports.” Yet when some digging around did turn up some information, it appeared that “Sidanco was cheap beyond belief.” The market capitalization implied that each barrel of its oil reserves was worth $0.15 at a time when the market price of crude oil was $20.

Hermitage bought more than a quarter of the available equity, 1.2% of the company, for $11 million.

In October 1997, BP announced that it was buying 10% of Potanin’s bloc. It did so at a 600% premium to the price Hermitage had paid a year before. There was nothing underexposed about Sidanco any longer. In fact, BP’s CEO and Potanin signed their deal in the office of Prime Minister Tony Blair. The diamonds were out of the rough and in the showcase, and Hermitage had its big win.

If We Had the Chance to Do It All Again

Sort of a win: the Sidanco deal, which appeared so rousing a success for Hermitage when BP stepped up, turned very sour for both of them. Potanin and friends launched a share dilution scam designed to push out or render irrelevant foreign interests. They tripled the number of shares outstanding, sold the new shares cheap to Russian interests, but locked out Hermitage in particular from buying. This led to the following dialogue between Browder and the apparatchik who brought him the news.

“If this dilution goes forward, it’s going to cost me and my investors … eighty-seven million dollars.”

“Yes, we know. That’s the intention, Bill.”….

“But how can you do this? It’s illegal!”….

“This is Russia. Do you think we worry about these types of things?”

Still later, as Putin turned against Browder, he found himself expelled from Russia, and in danger of arrest by Interpol. Hermitage itself was seized and turned over to a group of Russian nationals.

Russian authorities also arrested Browder’s tax lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky. Magnitsky was never brought to trial [while alive.] Instead, after a year locked up, Magnitsky (to whom Browder dedicates this book) was beaten to death by officers with rubber batons. Then he was tried and convicted of tax fraud.

The best we have by way of a happy ending is that both the U.S. Congress and the European Parliament passed Magnitsky Acts, providing for the seizure of assets from the Russian officials involved in Magnitsky’s death.