A recent report from the World Bank gives a sense of how much aid available through the world’s multilateral development banks (MDBs) is spent on the goal of “decarbonizing the world economy.”

A recent report from the World Bank gives a sense of how much aid available through the world’s multilateral development banks (MDBs) is spent on the goal of “decarbonizing the world economy.”

The report, available in full here, makes reference to six institutions in particular: the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; the European Investment Bank; the Inter-American Development Bank; and the World Bank Group.

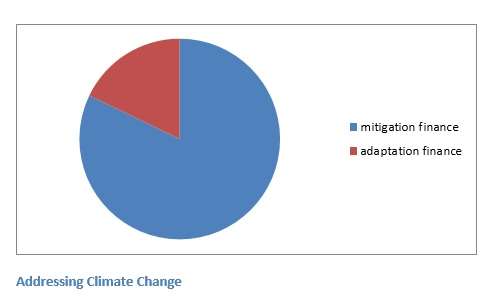

The bottom line: together the institutions names delivered more than $28 billion in financing in 2014 that “address climate change” in one of two ways. Most of that is in “mitigation,” that is, addressing the causes of climate change, especially in the development of non-carbon energy sources. Another $5 billion is for “adaptation,” that is, rendering the environment more human-friendly even on the presumption that climate changes continue.

For the purpose of the pie chart below, all “dual benefit” projects have been divided up into their mitigation-or-adaptation components.

Source: Adapted from 2014 Joint report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance

This of course brings to mind discussions of climate change here at AllAboutAlpha over the years, including a fascinating exchange earlier this year between Charles Skorina and Doug Friedenberg, over whether asset managers have a fiduciary obligation to divest – or to refuse entreaties to divest – from the fossil fuel industry.

Recalling the Exchange on Divestment

Skorina kicked this off on March 3, inspired by Global Divestment Day, three weeks before. Skorina’s analysis works from the premise (integral to CAPM) that restricting diversification leads to sub-optimal results. Divesting of fossil-fuel related business, then, can be expected to have a cost. The obvious questions are: how high a cost? And, a cost to be measured against what benefit? If the cost is substantial, and the benefit is (in the words of David J. Skorton, president of Cornell, cited by Skorina), predominantly that of making a “symbolic gesture,” then the endowment manager’s fiduciary obligations have been violated.

Friedenberg replied that the benefits aren’t at all symbolic. He said that a “tipping point” is approaching, at which climate change becomes undeniable and the value of carbon-industry-related assets will plunge in value. The benefit of an institution’s investment is that it gets the beneficiaries of that portfolio out of the way of the damage that will be done to their interests if they are still heavily invested in such assets the day after the tipping point.

Friedenberg of course ended his post with a piece of advice to divestment activists, and anti-carbon activists in general.. They ought to make their case not just to those who might sell such assets, but to those who might actively short them. There is nothing aggressive hedge fund managers prefer to “a good short story, especially a good short macro story,” he said.

Climate Change Finance by Benefits (USD Millions)

| MDB | Adaptation Finance | Mitigation Finance | Dual Benefit Finance | Total Climate Finance |

| Asian DB | 719 | 2,137 | -- | 2,856 |

| African DB | 756 | 1,160 | 0 | 1,916 |

| EBRD | 197 | 3,849 | 65 | 4,111 |

| EIB | 130 | 5,083 | -- | 5,214 |

| IDB | 109 | 2,352 | 0 | 2,461 |

| IFC | 8 | 2,540 | 0 | 2,558 |

| WB | 3,107 | 6,122 | --- | 9.229 |

| Grand Total | 5,036 | 23,243 | 65 | 28,345 |

Source: Table A1, 2014 Joint report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance

Getting the Date Right

That last bit suggests after all that Friedenburg and Skorina might not have been as far apart as their essays make it seem at first blush they are. After all, endowments are not hedge funds. Endowments are expected to play it safe; hedge funds to take informed risks. The notion that a tipping point is coming along (soon but no-one-can-say-when) is as much trap as opportunity. After all, the difference between making money and losing it is often a difference in dates.

If a hedge fund goes all in on the short case for, say, coal: it may lose everything before that tipping day arrives. Then, when it does arrive, the former employees of the fund, while standing in the unemployment line, can say, “I told you so!” Will that be a consolation? Probably not, but they’ll know they were engaged in an explicitly speculative endeavor, risking the money of qualified investors. That might be.

Perhaps the combined and implicit Friedenberg/Skorina position, then, is that anti-carbon activists should make their case to aggressive hedge fund managers rather than endowments.

Back to the World Bank

Getting back to the WB report, though: if the tipping point does come soon, then the expenditures that MDB’s are making in this area should be or should become self-supporting. Consider money spent on facilities that create useful energy from the wind. A mitigation project listed in the report will make expenditures of approximately $900 million to create 10 wind power plants expected to become operational over the next two years. This will constitute investment in assets bound to increase radically in value after such a tipping point.

Long/short equity hedge funds would presumably be interested in playing both sides of the upcoming tipping point: going short coal and going long wind.

Unfortunately, on both the wind and the coal side, even if the overall trend is certain, the timing of that “point” is tricky and extremely risky. This does not sound like an endowment’s play.