I’ve written about risk parity here before. Cliff Asness has kindly given me a chance to do so again, with a new paper about the proper perspective in which to view recent performance figures.

Start with the basics, the RP portfolio is defined by its contrast with the Capital Asset Pricing Model. RP entails two changes vis-à-vis the traditional CAPM portfolio. First, a reduction of equity, down from the traditional 60%: A manager switching to RP will sell stocks and use them to buy more conservative assets until the overall risk posed by his holdings via the latter catches up with the risk posed by his holdings of the remaining stock.

Second, the RPP manager will increase leverage, generally through the use of derivatives. This allows him to goose his returns, which will otherwise suffer from the sale of all those stocks.

There were claims, oddly, that the spread of such portfolios made a significant contribution to the market turmoil of this August. A team of analysts at Bank of America in particular contended that the leveraging of portfolios this entails creates a dangerous feedback loop. Increased volatility causes the managers using such a system to deleverage, which in turn can increase volatility.

That argument didn’t make, and didn’t deserve, converts. It is much more plausible, after all, to attribute that month’s fluctuations in the U.S. to the contagious consequences of China’s summer turmoil, and nobody has blamed RP portfolio strategists for that. If domestic causation is required for some reason, there’s a case to be made that the proliferation of new financial products that allow for speculation on VIX has helped create new volatility for the object of that speculation, volatility for volatility, and that this chicken came home to roost in August.

Those two points are more than sufficient to account for the phenomena and Ockham’s razor should shave away the B of A team’s guesswork.

A Real but Modest Edge

Still more fundamentally, the flutterings of August don’t look all that impressive in the rear view mirror, so the argument based on those flutterings won’t make any more converts now. What might be more important in turning heads one way or the other might be … oh, I don’t know … a comparison of actual performance?

Asness of AQR is an advocate of the risk parity model. He believes that it offers a “real but modest long-term edge over traditional approaches.” In the recent publication, though, he acknowledges that recent months have been a “tough relative performance period” for RP, and that if critics of the policy hadn’t gone “all tin-foil-hat” over the August sell-off they would have focused on this recent weakness.

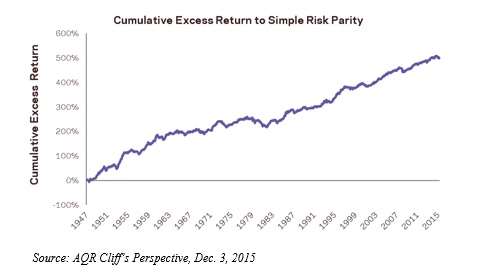

Asness puts this weakness it into a broader context. The cumulative excess return from what Asness calls “simple risk parity,” (a calculation based on a hypothetical portfolio) continues to rise steadily though undramatically. As the graph below indicates, this strategy had a falling off during the bursting of the dotcom bubble at the start of the new millennium. A few years later it had another falling off during the global financial crisis. But there’s been nothing “weird or unpleasant” lately.

Now for Relative Performance

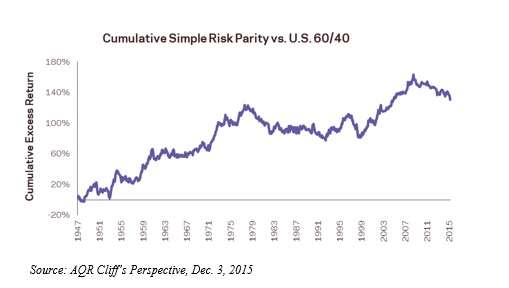

Still, when one looks at relative performance, the performance of risk parity against those traditional 60/40 portfolios, one does see a recent weakness.

The downward movement on the right-hand edge of this graph is what is at issue. Asness explains that it follows from one of the basic features of RP, that of “diversification away from equity dominance.” Equities hit their historic low in 2009 and have been making a warrior’s contribution to lots of portfolios in the years since. Obviously, this warrior has been fighting more vigorously for the traditional portfolios than for the RP variants.

This is, Asness concludes, no cause for alarm. It is a “painful but relatively normal occasional outcome if we’re implementing the process we think we are.”

Of course, particular traders might claim that they would have made adjustments to their RP portfolio, making it somewhat less RP-ish, that would have avoided this relative downturn. Asness acknowledges this. Indeed, AQR itself offers portfolios that tilt away from RP as signals dictate. But, he writes, this is a tactical decision, one that doesn’t affect the case for RP on the level of strategy.

It is well to remember that the terms “tactics” and “strategy” come from the military, and that the distinction is a matter of horizon. A general is thinking strategically when he picks the time and ground for his battles (or, a less adept general is failing to think strategically when he lets the adversary pick them). A general is thinking tactically as he is fighting one of those battles.