By Andrew Beer New products are sold on a story. For alternative multi-manager mutual funds – most of which have launched since 2012 – the pitch goes something like this: we can find top tier hedge fund managers to run various alternative investment strategies – equity long/short, relative value, macro, etc. – within a ‘40 Act fund and deliver “hedge fund performance with daily liquidity, lower fees and better transparency.” Is this realistic? After all, the ‘40 Act structure places a number of constraints on how those managers can invest – limits on shorting, illiquid assets, derivatives and leverage. Skeptics argue that managers have to fight with one hand tied behind their backs. AMMF marketing teams countered that fee savings would offset any lost performance. More aggressive players argued that retail investors would come out ahead. Well, the data is in and, it turns out, constraints matter. A lot. To simplify, from 2012 through 2015 AMMFs:

- Returned approximately 2% per annum net of fees

- Underperformed hedge funds of funds after fees by 200 bps per annum

- Fees and expenses consumed more than half of returns

- Returns to investors were generally taxable at a high rate

A discussion of the methodology and results follows.

A Brief History

The AMMF gold rush kicked off in 2012 when Fidelity announced that it would allocate $600 million to Arden Asset Management for a newly-formed AMMF. The knock on some existing AMMFs was that they could only attract B and C players to manage the sleeves (at 1% vs. the 2/20 quality hedge fund managers expect). But Arden, with Fidelity behind them, elevated the game. Now, every hedge fund had to at least consider it. With defined benefit plans in inexorable decline, and defined contribution plans on the rise, top tier managers could build a track record as a sub-advisor in anticipation of a flood of DC and retail assets – without doing it directly and potentially killing the 2/20 golden goose. Most interpreted this as the start of a deluge from DC plan assets. 10% of trillions of dollars is … a lot. Fidelity, a leader in the target date fund space, would pave the way. Soon other big DC players had to jump in. Within months of the Arden launch, dozens of new AMMFs were in the works. But was this an industry wide head fake? The obvious problem is fees: large DC plans balk at paying 250 bps for anything. Recent Department of Labor rulings won’t help. Mediocre performance eliminates any sense of urgency. As the doors to DC plan assets remain shut, most sponsors shifted their marketing efforts to the retail/RIA channels. This is where we stand today.

Performance Results in More Detail

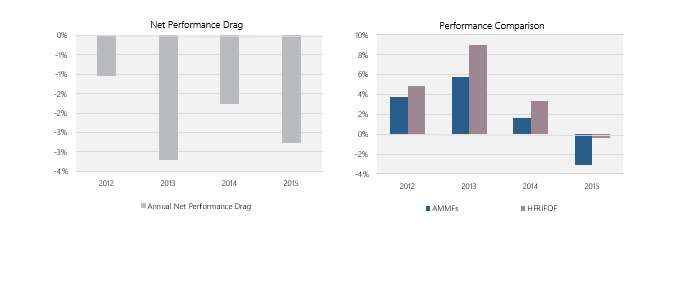

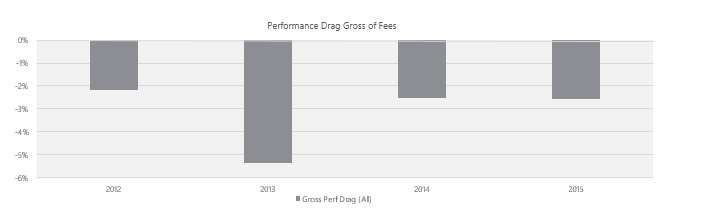

We currently track the performance of 32 mutual funds that fit the AMMF model: a manager hires sub-advisors to run hedge fund-like sleeves. One fund started as early as 2002, but the vast majority were launched since 2012; prior to then, the number of funds is sufficiently low that we do not consider the results conclusive. For each calendar year, we take an equally weighted portfolio of funds that have full year performance data and calculate the net of fee return. We compare those results to the HFRI Fund of Funds Index – a good representation of the performance of institutional hedge fund portfolios but perhaps with a slightly higher fee structure. In every year, AMMFs underperformed the HFRIFOF index – on average by over 200 bps. The chart on the right shows a net performance comparison, and the one on the left the net performance drag. The argument “you’ll make it back in fee savings” simply has not been true. When you lose 300 bps off the top (see chart below), 100 bps or so in savings does not get you back to even.

The argument “you’ll make it back in fee savings” simply has not been true. When you lose 300 bps off the top (see chart below), 100 bps or so in savings does not get you back to even.  What this demonstrates is that the absence of constraints in hedge fund vehicles is a key component of how they can make money over time.

What this demonstrates is that the absence of constraints in hedge fund vehicles is a key component of how they can make money over time.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize the results in an integrated way. From 2012 through last year:

- Before fees, hedge funds returned a little over 7.5% per annum – not bad at all in a zero interest rate environment.

- Those same, or comparable, managers generated returns of around 4.5% per annum within the constraints of AMMFs – in other words, constraints cost 300 bps or almost 40% of returns.

- AMMF investors paid fees and expenses of 2.6% on average, or more than half of gross returns.

- AMMF investors ended up with annual returns of around 2% per annum before taxes.

- Virtually all gains were taxable, often at high rates.

To be fair, there are a few standout performers – Blackstone’s product leaps to mind – as there will be in any population of funds. Some growing pains – like surprisingly high beta during the October 2014 drawdowns – were largely resolved by last summer. However, other risk management issues caused several funds to end 2015 down double digits – tough to stomach when the pitch is based on steady returns and capital preservation. With hot money looking for the exit, expect some sponsors to shoot the wounded this year. Not surprisingly, the refrain from many potential investors has been “why bother?” The diversification argument falls apart if most hedge fund alpha is lost in the repackaging. Yes, this has been a very, very tough investment environment; however, high expectations are warranted when fees are high, strategies opaque, and effective tax rates punishing. 2016 will be telling. AMMFs compete with lower cost hedge fund-like mutual funds that seek to deliver similar results – low equity beta, capital preservation and consistent returns above cash – but do so with internal teams. Without the two layers of fees, costs are much lower. Plus, those funds put up much better numbers over the past few years – in line with the HFRIFOF net of fees or 200 bps better than AMMFs. It’s not surprising, then, that one fund alone raised over $3 billion last year while the AMMFs were fighting for market share. Like in many things, maybe the simpler approach is better. Andrew Beer, CEO: At Beachhead, Mr. Beer oversees all marketing and research efforts and is influential in portfolio construction. Mr. Beer began his career in mergers & acquisitions at the James D. Wolfensohn Company, a boutique firm founded by the forthcoming President of the World Bank. Mr. Beer worked in leveraged buyouts at the Thomas H. Lee Company in Boston during his tenure at Harvard Business School. Upon graduating, he joined the Baupost Group, a leading hedge fund firm, as one of six investment professionals. Additionally, Mr. Beer co-founded Pinnacle Asset Management (leading commodity fund) and Apex Capital Management (Greater China hedge fund). Mr. Beer is an active member of the Board of Directors of the US Fund for UNICEF, where he serves as Chairman of the Bridge Fund, an innovative financing vehicle designed to accelerate the worldwide delivery of life-saving goods to children in need. With his wife, Mr. Beer is a co-founder of the Pierrepont School, a co-educational K-12 independent school located in Westport, CT. Mr. Beer received his Master in Business Administration degree as a Baker Scholar from Harvard Business School, and his Bachelor of Arts degree, magna cum laude, from Harvard College.