Introduction

In this segment of our series on Allocating to Risk-Managed Strategies we explain the benefits of hedging equities in a portfolio or investment strategy. You’ll learn:

- How institutional investors effectively employed a hedged equity strategy during the economic recovery period beginning in 2010.

- Why the next decade may be poised for higher levels of volatility and how hedged equities may provide an effective defense.

- How correlation between markets has risen, leading to the rise in popularity of long/short and covered call strategies.

What does it mean to hedge equity exposure?

- The performance of traditional equity investments, or “unhedged equities,” tends to rise and fall with the stock market. These investments include individual stocks, long-only mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

- Some alternative investments, such as equity long/short and covered call strategies, are referred to as “hedged equities” which seek to reduce portfolio risk while maintaining equity exposure.

- The term “hedged equities” does not necessarily mean long and short equally offset each other. Rather, that a measure of risk control is in place.

An Institutional Response to Volatility

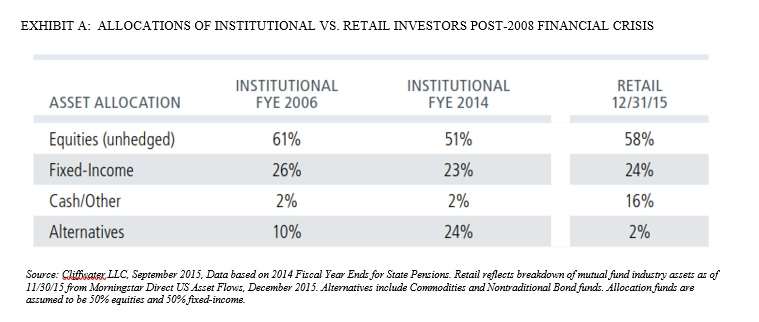

Compared to individual investors, institutional investors have less exposure to traditional, long-only equity investments.

After the 2008 financial crisis, institutional investors recognized that market volatility and high correlations among asset classes called for a revised approach to portfolio allocation. In response, many state pension funds reduced unhedged equity risk in their portfolios by sharply increasing allocations to alternatives; some, in the form of hedged equities.

Individual investors, on the other hand, continued a traditional allocation with comparatively more unhedged equities, much more cash, and much less in risk-managed strategies such as alternatives

Individual investors’ high allocations to cash—on average 15% of assets—essentially shows a simpler reaction to the same issues that prompted institutional investors to increase allocations beyond long-only strategies. In our view, a more strategic response for individuals would be to increase exposure to hedge equities.

We believe that increasing exposure to hedged equity strategies may provide the downside protection—and therefore emotional reassurance—that individual investors need to stay in the market. Why? This allocation strategy helps address market volatility. With potential for downside protection in place, investors may avoid running to the sidelines and missing out on gains—as happened during the bull market that began in 2009.

Volatility

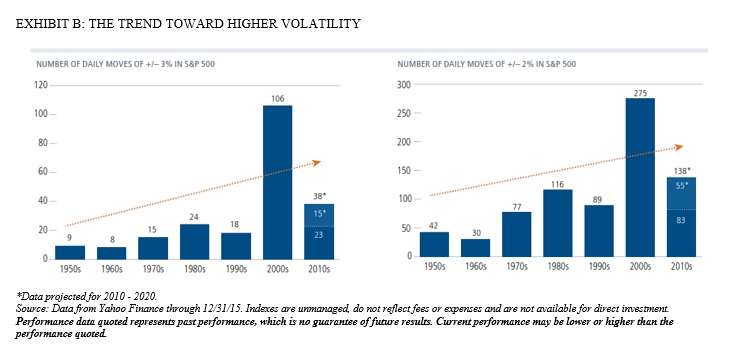

The long-term trend is toward higher volatility. Even setting aside the highly volatile 2000s, our current decade is on track to exceed average values for five decades from 1950-1999 by a large margin.

During the 2000s, we experienced more down days than the prior five decades combined. The 2000s included two drawdowns in the S&P 500 Index of more than 40%. A growing consensus holds that the greater incidence of large daily swings is more structural than temporary.

One reason for higher structural volatility may be technology that has interconnected markets and increased the velocity of trading. When investors decide to de-risk portfolios at the same time, the result can be like a game of musical chairs in which each investor seeks to avoid being the last to hold an unwanted asset.

While technology gives investors better, faster information and trading tools, it also creates a conduit for volatility particularly due to algorithmic trading. As we have seen, this can lead to a scenario whereby a scare in one corner of the market can quickly spread and intensify.

Potential for Mean Reversion

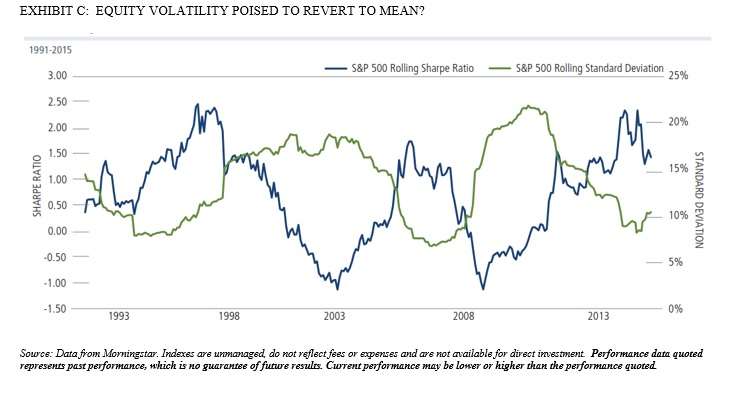

Although the long-term trend is up, equity volatility has been low in the years since the financial crisis. This period of calm is likely due, in part, to the Fed’s actions to keep interest rates near zero and reflate asset values. Exhibit C shows the three-year rolling standard deviation for the S&P 500 Index (green line). Note how its value has fallen more than 10 percentage points during the bull market that followed the financial crisis. The chart also displays the three-year rolling Sharpe Ratio for the S&P 500 Index (blue line). Bull market returns combined with low standard deviation has pushed the three-year Sharpe Ratio to near-record territory. [The Sharpe Ratio, named for Nobel laureate William Sharpe, is a measure of risk-adjusted return. It measures the average return earned beyond a level deemed to be risk-free (i.e., Treasury notes) per unit of volatility (standard deviation of the return series).]

Because markets are mean reverting, it’s unlikely that the figures shown above will remain at or near their 25-year extremes for an extended period of time. The likelihood of a reversal is increasing. A reversion, however, does not necessarily imply a severe pullback. Rather, it illustrates the inverse relationship between equity returns and volatility.

Emotional Effects of High Volatility

With long-term market volatility trending up and expected to increase in the short to intermediate term, what are investors’ options?

One option is to do nothing and continue holding unhedged equities. History suggests this approach may succeed in the long term. However, not all investors have a long-term horizon. Those in or nearing retirement are unlikely to have time to recover from significant losses.

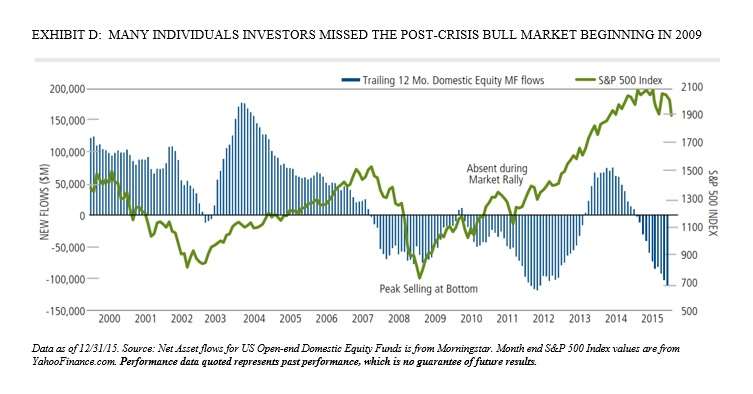

Another option is to reduce equity holdings and move those funds to cash or Treasuries. This approach limits investors’ potential to benefit from market gains as demonstrated following the last bear market when many investors were absent during the subsequent rally. Exhibit D shows net equity flows for individual investors, on a 12-month trailing basis into and out of domestic equity mutual funds. Only in 2013—four years into the bull market—did net flows flip from negative to positive.

The fact that many individual investors missed much or all of the post-crisis bull market points to the emotional toll caused by a severe draw-down and high volatility.

In considering the flow data, it may be reasonable to expect the average individual investor cannot hold unhedged equities and stay fully invested across full market cycles. Even those who believe they are committed to holding positions—such as those with decades before retirement—may be unable to actually do so particularly during severe draw-downs.

By making the decision to hedge a portion of their unhedged equity holdings, investors may be better able to stay the course and weather the storms. This way, hedged equities can serve as tools to address the human response to market conditions, which may be increasingly important given the historical shift of “typical” market behavior toward higher structural volatility.

Loss aversion and the individual investor

- First demonstrated by Daniel Kahneman, loss aversion refers to the preference of avoiding losses over acquiring gains. In fact, some studies suggest that a given loss may produce a negative response that is twice as acute as the positive feelings provided by a gain of equal value.

- For investors, the preoccupation with avoiding losses has resulted in short-term investment views and consistently ill-timed moves out of the market. As shown in Exhibit D, loss aversion tendencies resulted in missing out on potential gains over time including the most recent market rally.

Correlations and Diversification

Along with rising structural volatility, higher correlations among assets have also increased the inherent risk of unhedged equities.

The organizing principle of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) is that combining assets with low correlations to each other can reduce portfolio variance and improve risk-adjusted returns.

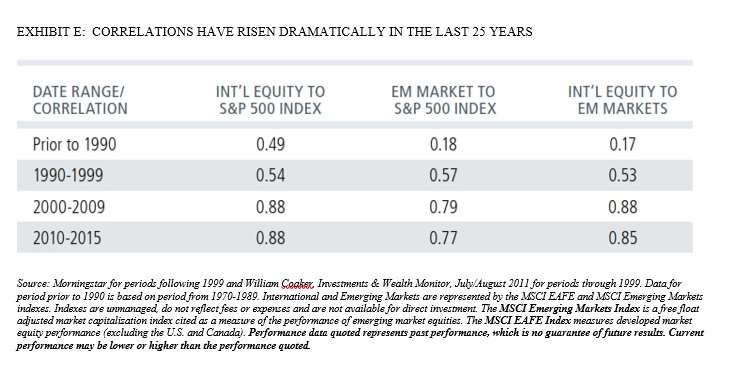

For example, many investors diversify their equity exposure internationally, with both developed and emerging market holdings. Prior to 1990s, the long-term correlation between international (developed) equities and the S&P 500 Index was under 0.5. The pre-1990 value for emerging markets was even lower, at 0.18. These relatively low correlations allowed meaningful diversification while staying within equities as a broad asset class.

Note how much correlations have risen in the last 25 years (Exhibit E). Now, the S&P 500 Index is highly correlated to both international developed and emerging markets. Such increases in correlations may underscore the need for including hedged equity strategies in a well diversified portfolio.

As a risk management tool, hedging offers significant benefits relative to solely diversifying across types of equities. Given that the majority of risk in a diversified equity portfolio is market-based risk (rather than company-specific risk), it cannot be diversified away in a long-only portfolio. However, hedged equities, by design, can address market-based risk.

Types of Hedged Equity Products

Two types of equity strategies may be especially useful to investors seeking to hedge a portion of their equity exposure.

- Long/Short Equity: Managers of long/short equity strategies seek to benefit from stocks that are appreciating in price as well as from those that are declining in price.

- Goal: Achieve equity-like returns with less volatility than the equity market

- Strategy: Profit from stocks that are going up as well as those that are going down

- Covered Call Writing: Managers of covered call strategies seek to reduce risk and generate income from:

- writing call options against long equity positions

- purchasing puts to provide downside protection to the portfolio

- Goal: Achieve lower volatility than equity markets or long-only funds, while also providing income

- Strategy: Write call options against long equity positions and purchase puts to hedge downside risk

Summary

In summary, the long-term trend points to higher volatility and increased correlations among assets. The implications of this trend for unhedged equity portfolios may be exposure to unintended risks when relying on diversification. To help manage market-based risk, which cannot be achieved through diversification, the use of hedged equity strategies as portfolio diversifiers may provide a solution. Such an approach may likely benefit individual investors by mitigating the overall volatility of investment portfolios and enabling long-term market participation without ill-timed moves out of the market.

Correlation is a statistical relationship between two variables. A positive correlation occurs when two variables move in tandem–one variable increases as the other increases and vice versa. Negative correlation occurs when they move in opposite directions–one variable increases as the other decreases and vice versa.

Diversification does not guarantee profit or eliminate the risk of loss.

Draw-down is the peak-to trough decline during a specific record period of an investment.

S&P 500 Index - Considered generally representative of the U.S. large-cap stock market.

Sharpe ratio is a calculation that reflects the reward per each unit of risk in a portfolio. The higher the ratio, the better the portfolio’s risk-adjusted return is. Standard deviation is measure of volatility.

Portfolio Variance is the measurement of how the actual returns of a group of securities making up a portfolio fluctuate. Portfolio variance looks at the standard deviation of each security in the portfolio as well as how those individual securities correlate with the others in the portfolio.

This material is distributed for informational purposes only. The information contained herein is based on internal research derived from various sources and does not purport to be statements of all material facts relating to the information mentioned, and while not guaranteed as to the accuracy or completeness, has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable.

Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations.

Risks of alternative investments

Alternative investments may not be suitable for all investors, and the risks of alternative investments vary based on the underlying strategies used. Many alternative investments are highly illiquid, meaning that you may not be able to sell your investment when you wish to.

Long/short equity: The principal risks of investing in a long/short equity strategies include: equity securities risk—securities markets are volatile and market prices may decline generally; short sale risk—a portfolio may incur a loss without limit as a result of a short sale if the market value of the security increases, a portfolio may be unable to repurchase a borrowed security; leverage risk—certain transactions such as loans and securities lending may create leverage and cause the fund to be more volatile; foreign securities risk—fluctuations of exchange rates may affect the U.S. dollar value of a security. Covered call writing: As the writer of a covered call option on a security, the fund foregoes, during the option’s life, the opportunity to profit from increases in the market value of the security, covering the call option above the sum of the premium and the exercise price of the call.

Some of the risks associated with investing in alternatives may include hedging risk – hedging activities can reduce investment performance through added costs; derivative risk- derivatives may experience greater price volatility than the underlying securities; short sale risk - investments may incur a loss without limit as a result of a short sale if the market value of the security increases; interest rate risk – loss of value for income securities as interest rates rise; credit risk – risk of the borrower to miss payments; liquidity risk – low trading volume may lead to increased volatility in certain securities; non-U.S. government obligation risk – non-U.S. government obligations may be subject to increased credit risk; portfolio selection risk – investment managers may select securities that fare worse than the overall market. Alternative investments may not be suitable for all investors.

© 2016 Calamos Investments LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Calamos® and Calamos Investments® are registered trademarks of Calamos Investments LLC.