Northill Capital, a London-based asset manager, has released a report defending active asset management from the common charge that it cannot, after costs, beat the passive managers. That is an old and familiar subject for debate.

What cannot be debated, because it is a simple matter of definition and arithmetic, is this: for any given market, alpha nets out to zero. The market as a whole cannot outperform the market as a whole. Those who do outperform the whole, then, must do so because others underperform.

If an index tracking a certain market or sector is doing its job, then alpha as defined against that index will, again, net out to zero. This fact doesn’t exclude the possibility that such factors as managerial skill might play a role in determining who is on the positive side before this netting. By trying to elucidate that possibility, one wades into a bloody crossroads.

Adding Something New

Where Northill adds something new to this familiar ground is in the distinction it draws between specialists (whom it calls “focused” asset managers) and unspecialized, presumably unfocused, generalists. In the words of partner Jon Little, “This report provides evidence of a persistent link between asset managers focused on one asset class and their success in delivering outperformance to investors.”

The problem with generalists? The report contends that part of their problem with trusting your wealth to a generalist is the continual distraction such folks suffer from the launch or new investment strategies or products, when they ought to stick to their cooking. Also, generalists can easily fall into the trap of growing their Assets under Management beyond their capacity; this is less of a problem for those management teams committed to making one investment process work. Finally, even when generalism seems to work, it will work by virtue of the talents of one or a few key people, and investors are rightly wary of this “key man” risk. The key man can always be run over by a bus. A single strategy approach allows for a “collegial, team-oriented” culture.

How to tell who the generalists are, and who are the specialists? That can be tricky, Northill contends. The authors say that “many examples exist of managers that would appear to be focused’ but that in fact operate “separate, unrelated investment processes within the same asset class, or even within the same ‘multi-strategy’ fund.” How can an investor weed out those situations? The answer: due diligence has to be qualitative, not merely quantitative.

Methodology

Nonetheless, quantitative statistics can give one at least a first approximation of who counts as focused. The authors of the study, who treat especially of focus on active U.S. equity strategies, say that for the purpose of measuring focus quantitatively they have used the share of the manager’s total AuM represented by such U.S. equity strategies. They ranked each of 496 asset managers on this basis, divided them into quartiles and deciles, than employed Mercer’s Global Investment Manager Database to match each ranking with performance.

Let’s dispense with a couple of methodological points before we get to the results. To minimize any distortion from survivorship bias, Northill shaved from the database any managers who did not have at least one strategy with a 5 year track record. It also excluded very small managers, that is, less than $50 million AuM, and very large managers, that is, those with more than $100 billion AuM. Finally, it defined the deciles defined by the number of managers, not weighting them by asset, so that each ranking has either 49 or 50 active managers.

The Results

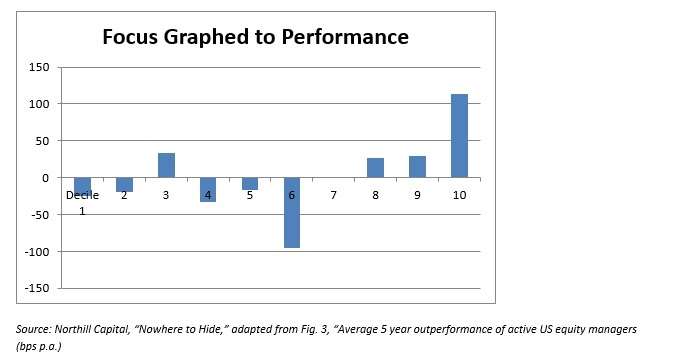

The 10th decile, that is, the group of managers ranked as most focused, had between 98% and 100% of their AuM in active US equity. These managers outperformed their benchmark by 114 basis points over 5 years.

Intriguingly, the worst performance wasn’t found among the least focused. It was found in the middle, the 6th decile to be precise, among manager who had between 46% and 61% of their assets devoted to this strategy. The outperformance of that strategy was -95 basis points: that is, 95 bps below the benchmark.

So there is no very close correlation between focus and performance along much of the graph, as shown above, but there is a clear upward move on the right-hand side of the graph, as focus nears completeness.

Northill finds similar evidence for focus-based outperformance in the statistics on the fixed-income strategy.