Preqin’s new Sovereign Wealth Fund Review makes the point that total assets under the management of SWFs continue to grow, but the rate of growth is notably slowing.

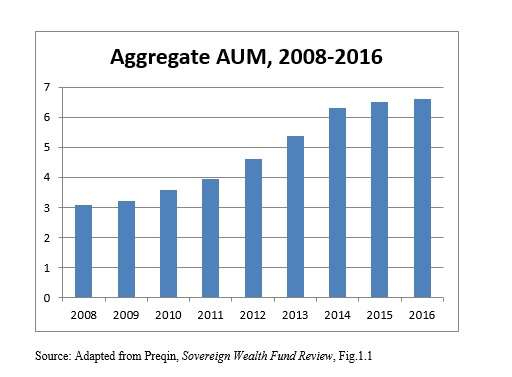

This graph, measuring in US$ trillions, illustrates the growth trend since the financial crisis.

Although the space grew by $.76 trillion between the end of 2012 and the end of 2013, and $.93 trillion the following year, it grew by only $.20 trillion in 2015 and less than half of that in 2016.

Lower Crude Prices

The slower growth may reasonably be attributed to lower oil prices and to the volatility of global markets. That growth continues regardless is a testament to the weighty reasons why sovereigns create such funds: capital maximization, stabilization, economic development.

The sheer size indicated on the right hand edge of that graph is impressive, as it represents AUM comparable to that of the entire alternative investments industry.

During the three-year period just before that covered by the above graph (2005-07), a time of high oil prices and a general optimistic sense that the good times would keep rolling, 25 new funds were created. Fund creation continues: the Turkey Wealth Fund, established last year ($14 million AUM) is an example of this. There are 20 different countries on the continent of Africa “currently discussing the implementation of a fund,” as the report says.

There is also a certain amount of shuffling that goes on in terms of the vehicles for these assets. In January 2017, the ruler of Abu Dhabi proclaimed the existence of the Mubadala Investment Company, which entailed the merger of two already-existing SWFs, the International Petroleum Investment Company and the Mubadala Development Company. (“Mubadala” is the Arabic word for an exchange or swap and sometimes takes on a technical meaning in discussions of Shariah finance.)

Such a merger by itself doesn’t change the amount of funds the sovereign in question has dedicated to the functions involved, of course. It’s a policy decision that can have a number of justifications: perhaps most obviously, a merger can alleviate the awkwardness that results when different funds of the same sovereign are competing with each other for control of the same assets or exploitation of the same market opportunities.

Preqin’s report mentions that there is in principle a distinction between sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises. The former are financial institutions and passive investors whereas the latter (SOEs) are strategic and active investors. In some contexts, notably in the People’s Republic of China with its “complex public sector driving the creation of various investment vehicles” on the one hand and its “foreign policy and acquisitions overseas” on the other, this distinction can get blurry.

More than half of the world’s SWFs (53%) are hydrocarbon funded. Most of the rest are non-commodity funds, although there is a sliver for space (1%) for SWFs funded by other commodities.

What Makes for a Successful SWF?

One question the report asks is: how can a sovereign do it right? Some funds are created for a reasonable goal but “end up being exhausted by the government for some other purpose.” Failure and capital depletion can result from “lack of governance, operating structures and control frameworks” and most importantly from inadequate independence of the SWF from political pressures.

A successful SWF, then, will generally be one that avoids those pitfalls, and that can do so with sufficient transparency that counter-parties know that it has avoided those pitfalls. As the report observes, such a fund “may want to seek co-investments in some of its ventures and those co-investors will only be prepared to go ahead” if the management of the fund itself has the market’s trust.

A New Feature

Preqin issued its first report on SWFs in 2008. The GFC of that time concentrated minds, and some of the newly concentrated minds wondered about these vehicles and what role they were actually playing in the world.

Preqin has issued further reports over the years since and this latest (2017) report includes a new feature, “information on real estate deals invested in and exited [by SWFs] as well as more analysis across investment portfolios” than was available in the earlier reports.