The Alternative Credit Council, an affiliate of the Alternative Investment Management Association, has put out a paper on the present state of the private credit industry, considering both the demand (from borrowers) for its services and the supply (from investors) of capital to lend.

In preparing this paper, the ACC has partnered with Dechert LLP, an international law firm that specializes in financial and regulatory intricacies, to research and present a discussion of how private credit has managed to “cement its place in the lending landscape globally.”

The term “private credit” refers to borrowing, especially although not entirely by mid-market borrowers, that is accomplished in the form of notes sold to qualified institutional buyers (QIBs). Such notes don’t have to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The 60 participants in this market who were surveyed for this paper collectively manage approximately $500 billion AUM. More than $350 billion of that is allocated to “committed capital,” also known as “drawn capital.” The remainder is the entities’ “dry powder.”

Not Just the Midmarket

One of the points of the paper is that private credit so understood is no longer stuck in the midmarket. It is moving outward in both directions. Money gets in this way to high-end borrowers where it may private credit to infrastructure and real estate-based operations. The private lenders may collaborate with banks when they expand that direction.

At the small-scale end of the lending spectrum, private lenders may find themselves supporting “trade finance, asset backed lending, and structured products.”

There is a good deal of optimism among participants in the survey, and among “commentators” more generally, that much as this market has grown, there is still more room for growth. After all, a persistent low interest rate environment has meant that many institutional investors have found it very difficult to deliver on their commitments. They have turned to investing in private debt funds.

On the other side of the market, there continue to be a number of borrowers who are good risks yet whose needs are not being met by the banking system, which is undergoing its own uneasy transformation in the face of regulatory pressure.

What the Borrowers Want

The top three characteristics of private credit that borrowers value most are: the speed of decision making, the ability to develop complex structures, and the flexibility of terms.

Relatedly: many midmarket borrowers are wary of over-relying on equity for their financing, thereby diluting the equity stake held by the core management group of the borrower.

The report quotes one private credit manager, specifically discussing the market in Europe, who said, “It’s not a question of too much money being raised – some countries are just developing more slowly. It’s a question of matching supply and demand.”

Enticing as Europe – and Asia – are, the U.S. market remains the cornerstone of the private debt industry. The research shows that European and U.S. based private credit managers give importantly different answers to the question, “what is the most resource intensive activity in carrying out private credit strategies?” In the U.S. the most popular answer is “sourcing credit opportunities.” In Europe, it is “conducting credit analysis.”

What’s the difference? As ACC and Dechert explain, the difference is one of emphasis (one of looking at opposite sides of the same coin) but not unimportant for all that. The phrase ‘Sourcing opportunities’ suggests Yankee glass-half-full optimism, whereas “conducting analysis” may suggest a more jaded European cynicism about prospective borrowers. The difference “may be a symptom of fiercer competition for target borrowers in the US relative to the European markets,” these authors suggest.

Shifting Negotiation Tides

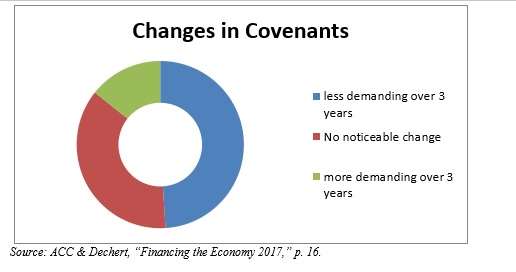

The report quotes a private credit manager in the United Kingdom who says, “It is a good time to be a borrower in terms of covenants and competitive terms.”

Covenants are often a good sign of the shifting tides in the negotiating position of borrowers and lenders. When lenders have the upper hand, they use covenants to protect their position contractually. As the competitive pressure increases on them to take the risks and make the damned deals, they often have to become more flexible about covenants.

Participants in this study were asked: “how has the degree of covenants in loan offerings changed over the past 3 years?” Nearly one-half of respondents said they have become less demanding (more pro-borrower). About a third said there had been no noticeable change, with the remainder saying “more demanding.” The donut below shows this point in graphic style.