By Skye Macpherson, CAIA, Global Head of Portfolio Management, and Ben Martin, Portfolio Analyst at Nuveen, LLC.

“Over the next four years, the U.S. will see renewable diesel refining capacity more than quadruple so that refiners and distributors can achieve compliance and supply low carbon transportation fuel in Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) states.”

As the effects of climate change have become more apparent, several U.S. states have enacted legislation to lower carbon emissions. The Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), originally developed in California and subsequently ratified in Oregon and Washington, establishes annual carbon intensity benchmarks for transportation fuels that decrease over time. The policy gradually decreases the amount of petroleum-based fuel within the transportation sector over a 20-year horizon.

The reduction in carbon-intensive fuels is achieved through a credit trading system wherein refiners or distributors generate credits by supplying fuel that has a carbon intensity below an annual benchmark set by the state. Debits are generated for fuels supplied that are above the benchmark, and a business maintains compliance with a LCFS when their credits equal or exceed their debits. As time has passed and the carbon intensity benchmark of fuels has decreased, the amount of credits traded and the value per credit has increased. For example, in California, 13.3 million credits were traded at an average price of $160 per credit in 2018. By 2020, the average credit price increased 24% to $199 with a total of 21.7 million credits traded. Clearly, LCFS incentivizes the production of renewable and less carbon-intensive fuels while making petroleum-based fuels more expensive.

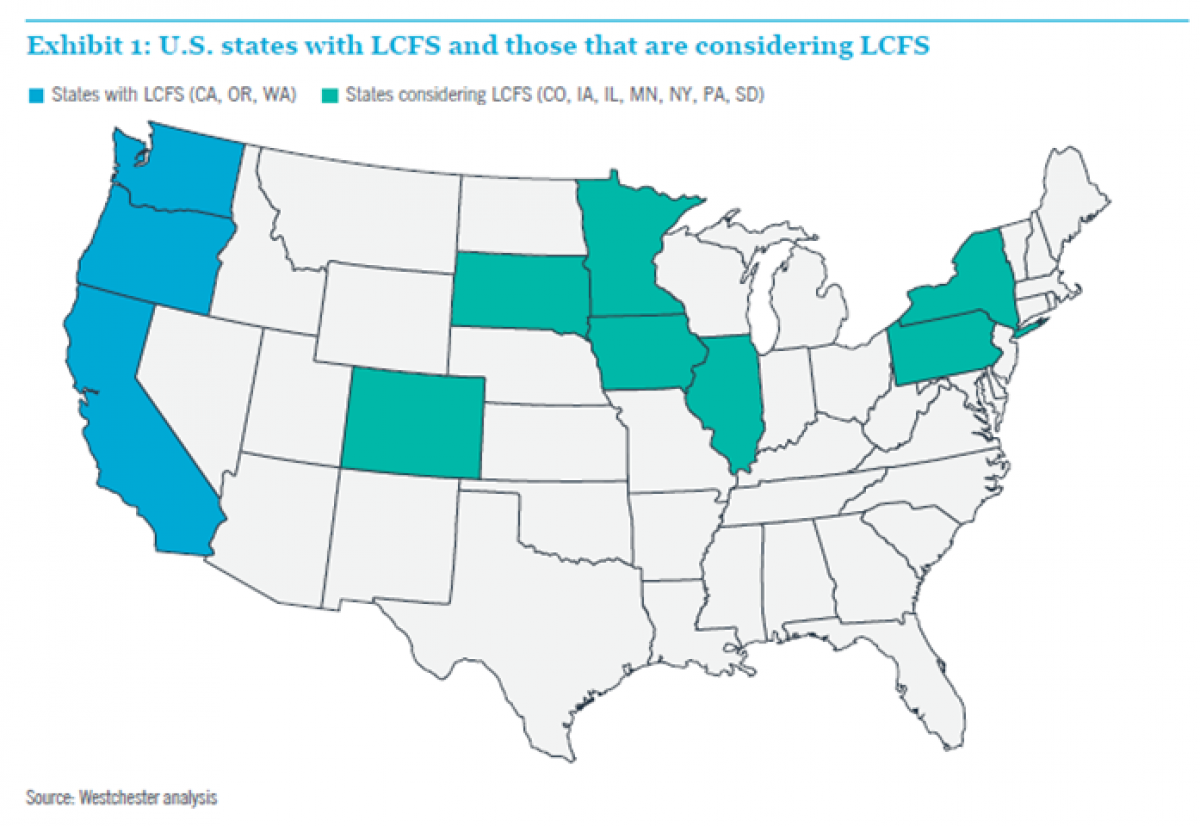

Currently, California, Oregon and Washington have enacted LCFS legislation. From a fuel demand perspective, California is the largest user of on-road diesel in the U.S., consuming more than 3.2 billion gallons in 2019. Washington and Oregon consumed 798 and 596 million gallons of diesel in 2019, respectively. This demand of 4.6 billion gallons of on-road diesel represents the current addressable market for renewable diesel. However, states such as New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois have considered similar policies. When the demand in these states is included, the addressable market size increases to 7 billion gallons, or about 17% of total U.S. consumption. The full list of states that have enacted or are considering LCFS can be seen in Exhibit 1.

RENEWABLE DIESEL VS. BIODIESEL

There is a common misconception that renewable diesel and biodiesel are one and the same product. While the two fuels are derived from the same feedstocks of fats and oils, the two are chemically different.

Renewable diesel is a hydrocarbon and is chemically identical to conventional diesel but refined from a renewable feedstock like used cooking oil, soybean oil or tallow. Renewable diesel can be produced, transported, and stored in the same facilities originally designed for petroleum-based diesel with modest capital expenditure. For diesel engines, no modification or additives are needed and no blending with petroleum-based diesel is required. This makes renewable diesel a drop-in, low carbon substitute for conventional diesel, with potential for a 50 - 85% reduction in carbon intensity relative to conventional diesel and up to a 10% reduction in NOx emissions. Considering California’s legislation only requires a 20% reduction in the carbon intensity of fuels by 2030, unblended renewable diesel is capable of more than covering that requirement.

While biodiesel is also produced from renewable feedstock, it is an ester that requires blending with petroleum-based diesel to be compatible in most engines. This blending requirement comes with a higher carbon intensity, making it a less attractive product to supply in LFCS markets, in addition to requiring separate facilities from existing diesel refining and distribution infrastructure.

The incentives offered by LCFS policies in addition to oil companies’ carbon reduction efforts have led to a spate of capacity expansion announcements for the refining of fats and vegetable oils into renewable diesel.

Exhibit 2 below shows refinery plans for converting or constructing renewable diesel capacity. As of early 2020, there were approximately 400 million gallons of renewable diesel produced in the U.S. A survey of the industry shows 1.9 billion gallons per year of incremental capacity due to come online by 2024. Over the next four years, the U.S. will see renewable diesel refining capacity more than quadruple so that refiners and distributors can achieve compliance and supply low carbon transportation fuel in LCFS states.

Exhibit 2: Renewable diesel refining capacity growth

So, where will the feedstock of fats and oils come from to enable this expansion?

The expansion of renewable diesel production in the U.S. will certainly increase demand for soybean oil and, ultimately, soybeans. Soybean and soybean oil prices have hit near multi-year highs in 2021. For soybean farmers, these price levels are considered an incentive pricing environment in which demand growth outweighs supply growth and commodity prices are typically determined by the highest cost producers. Thus, prices sit at a level that incentivize the highest cost producers to produce and weather events that limit production can cause price spikes, as has been the experience during the 2021 growing season in the U.S.

The U.S. is the major producer of several crops and its exchanges set global pricing benchmarks, the disappearance of acreage devoted to other crops could create upward pressure on a variety of soft commodity prices. Commercial farms are businesses, and profitability is the main factor determining planted acreage. The price of soybeans has increased significantly over the past year, but net returns would have to be consistently higher than other crops year after year to induce such a shift. Although there is precedent for acreage shifts, and specifically in response to renewable fuel mandates, the significant demand of the renewable diesel expansion could continue to place upward pressure not only on soybean prices, but other crops as well.

Farm profitability has seen an uptick with higher soybean and other agricultural commodity prices. Considering this new demand scenario for soybeans and the correlated nature of agricultural commodity prices, prices have the potential to remain elevated. This favors farmer margins if input costs can be managed, as those usually rise with farmer income. With healthy farmer margins come increased returns to land which could translate into both income and appreciation upside for farmland.

Please see the full paper which discusses further supply and demand consideration in addition to electronification of transportation vehicles. Low carbon fuel, farmland and climate change | Real assets | Nuveen

About the Authors:

Skye Macpherson, CAIA Global Head of Portfolio Management Nuveen, LLC provides investment advisory solutions through its investment specialists. Nuveen Securities, LLC, member FINRA and SIPC. 800.257.8787 | nuveen.com Skye oversees portfolio strategy, construction, and monitoring of Westchester’s farmland products, as well as leading the research, distribution and client services functions. Skye began working in the asset management industry in 2000.

Prior to joining the firm in 2019, she was a natural resources and agricultural equity portfolio manager at BlackRock. Skye graduated with a Bachelor of Agricultural Economics, with First Class Honours, from the University of New England. She also holds a Graduate Diploma in Applied Finance and Investments from the Securities Institute of Australia and the CAIA designation.

Ben Martin Portfolio Analyst Nuveen, LLC provides investment advisory solutions through its investment specialists. Nuveen Securities, LLC, member FINRA and SIPC. 800.257.8787 | nuveen.com Ben works as an Analyst for Westchester’s Portfolio Management team. He covers a broad range of tasks including fund reporting, market analysis, and support for various ESG initiatives. His practical knowledge of farm management and academic background in agricultural economics provides the team with insight on both the science and economics of production. Ben joined Westchester in April 2020 after spending two years as an analyst with Fall Line Capital.

While there, he worked on a regional team that managed row crop farmland throughout the southeastern U.S. Prior to that, he managed a diversified farm in his home state of Kentucky that produced thoroughbred horses, cattle, and various crops. Ben graduated with a B.S. in Agronomy from Texas A&M University and a M.S. in Agricultural Economics from the University of Kentucky.