By Jacob Miller, Chief Solutions Officer, Opto Investments

The Greatest Tailwind Ever Told

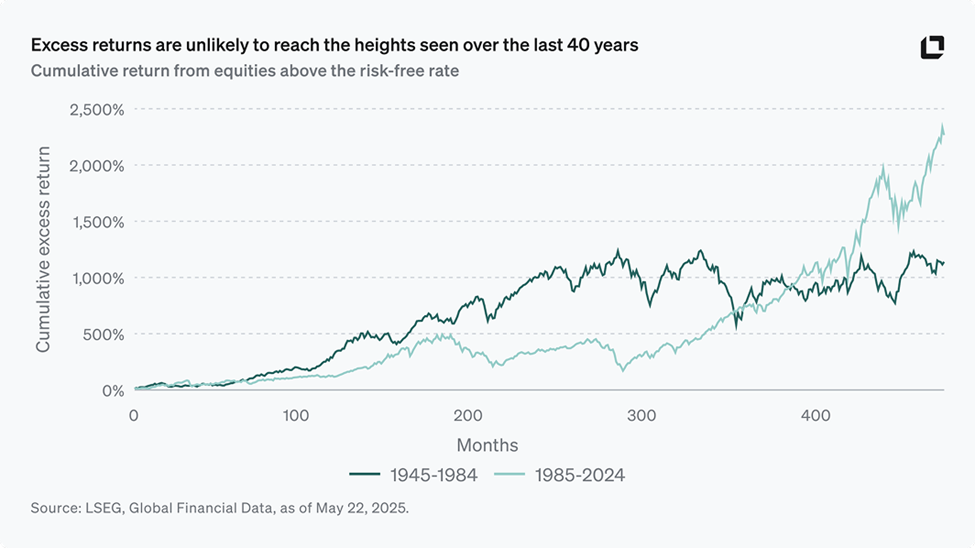

U.S. equities haven’t just been good for the last 40 years—they’ve been gift-wrapped, thanks to three macro forces that lined up like a NASA launch window:

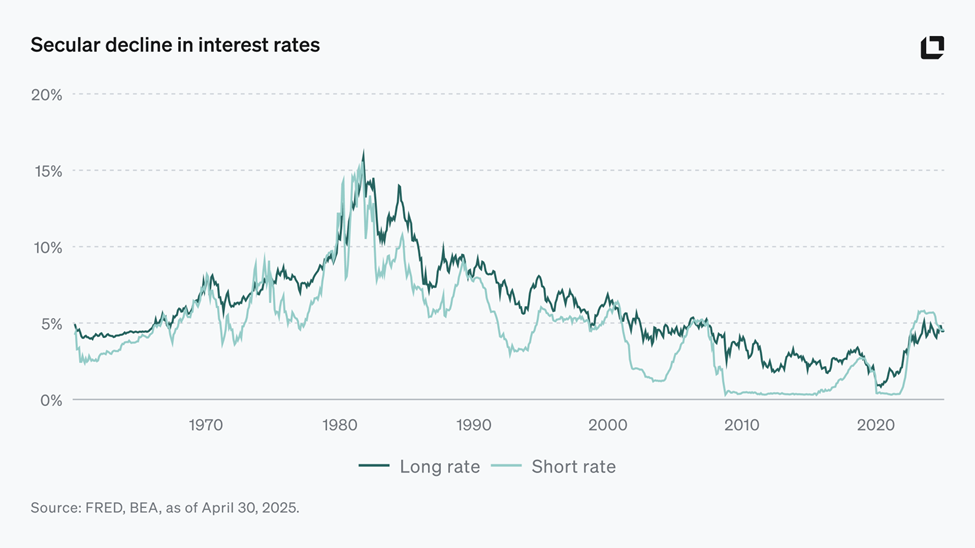

Interest rates that fell almost uninterrupted from Volcker’s 20% peak to near-zero

A historic surge in globalization that slashed costs and opened fresh demand

A wholesale technological shift from smokestacks to software. Ride those currents and even a mediocre stock picker looked like a genius.

Below, I unpack how each force juiced returns, then show what markets look like once the freebies are stripped out. (Spoiler: more than half the magic disappears). I’ll then tackle the headwinds now forming and finally dig into whether AI-powered productivity is a miracle, a mirage, or something in between.

From 1981 to 2021 the long bond yield plunged from 15% to <2%, and every hiking cycle topped out lower than the one before. Lower discount rates did two things at once:

Multiple expansion. When the denominator in a discount cash flow model collapses, today’s price balloons—no operating heroics required.

Margin boost. Cheaper debt trimmed interest expense, fattening net income even if revenue growth stayed pedestrian.

The chart is basically a ski slope. If you owned duration—bonds or stocks—you won. Simple as that.

2. Globalization: Two-Sided Windfall

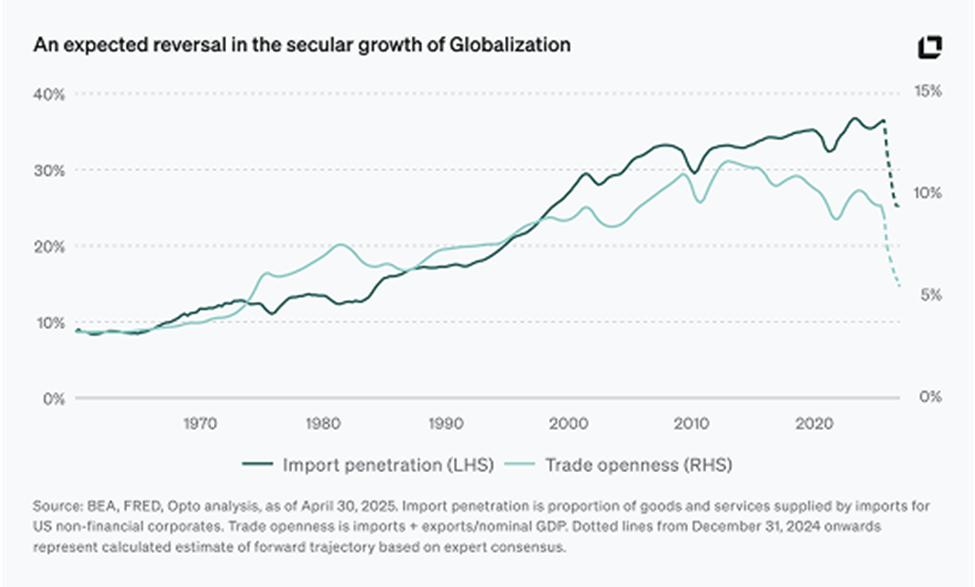

Offshoring migrated labor-intensive production to cheaper locales and opened the world as a sales funnel. Import penetration rose four-fold, while foreign sales for S&P-type companies nearly doubled as a share of revenue. Margins climbed on lower input costs; top-line growth accelerated as emerging markets bought the finished product.

Globalization simultaneously widened both jaws of the valuation vise: higher earnings and a fatter multiple via the “global growth story.” Either or both could tighten significantly from here, while a continued opening seems highly unlikely.

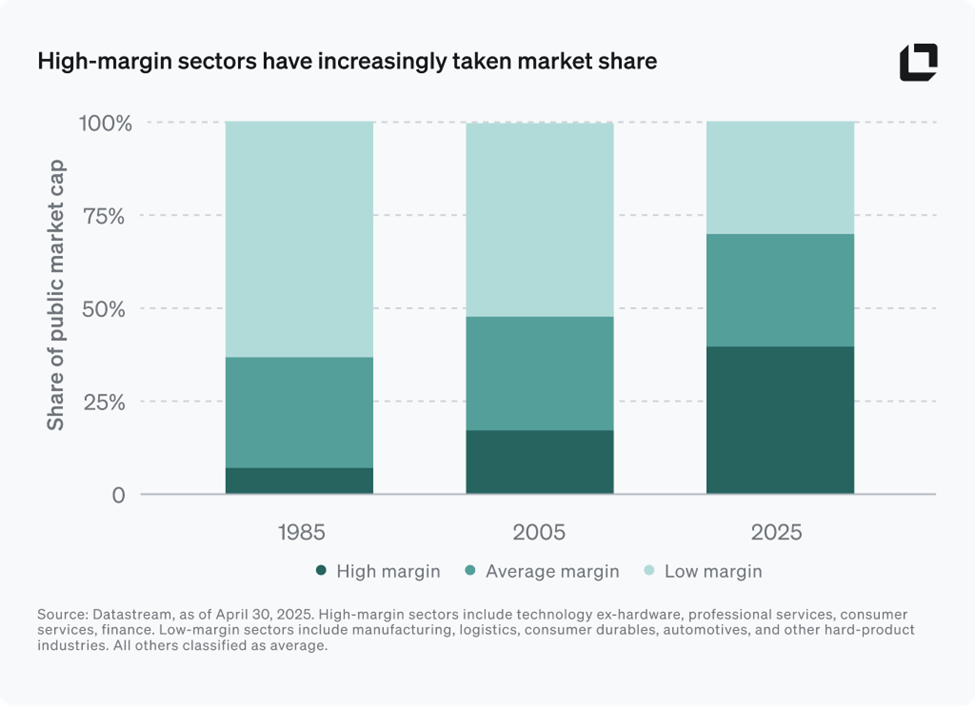

3. Sector Shift: From Steel to Silicon

In 1980, high-capex, low-margin industries (energy, industrials, consumer durables) dominated market cap. Four decades later, software and services rule. Tech’s asset-light model converts every marginal dollar of sales into profit at a rate Old Economy CFOs could only dream about. The index didn’t just grow; it re-mixed into higher return components, which, when viewed in aggregate, looked like margins rising for the index as market cap weights shrunk for low-margin sectors.

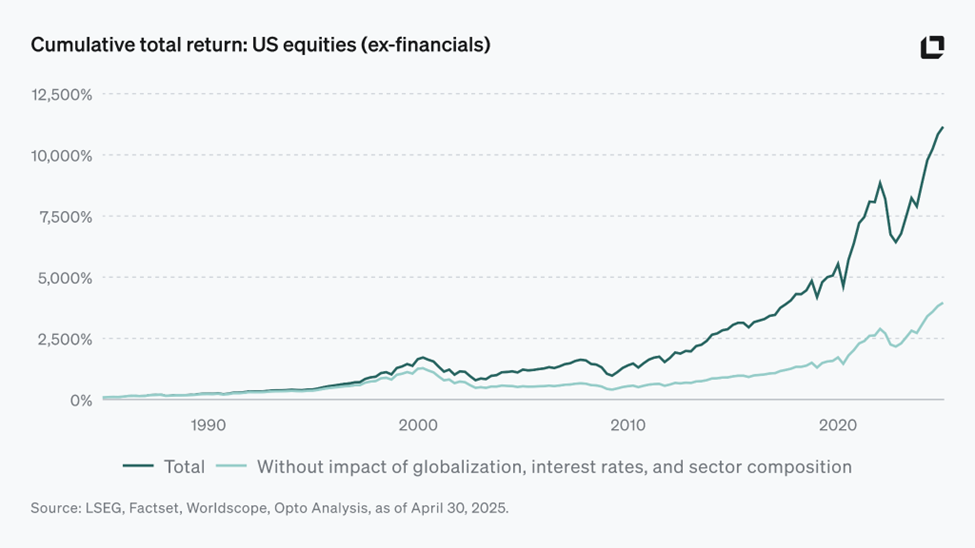

4. The Composite Effect: Half the Party Was Macro

Stack the three forces and the picture is stark. When we back-test U.S. equities excluding the benefit of (a) lower rates, (b) globalization, and (c) the sector remix, cumulative returns collapse by more than 50%. In several five-year windows, the entire outperformance is explained by those macros rather than by sales growth or real productivity gains.

Put simply, investors got paid twice: first through genuine operating improvement, then again through a macro multiple-rerate on the exact same cash flows. No wonder 60/40 felt invincible.

The last four decades were a textbook bull market in nearly all risk markets because the economic tide itself kept rising. If you built your strategic plan, glidepath, or personal risk tolerance assuming a replay, rethink it now. The sequel (rate tailwinds capped, trade fragmenting, tech already dominant) looks nothing like the original.

We are entering a new paradigm, where public markets are unlikely to deliver the kind of returns investors have come to expect, which makes diversifying into private markets essential.

Welcome to the Headwind Decade

The three tailwinds we unmasked in the first section (falling rates, hyper-globalization, and a perpetual march toward software and services) are either spent or flipping. The next 10 years will feel nothing like 1985-2021. Below is a blunt inventory of what happens when each booster rocket burns out and why raw productivity (read: AI) is now the only lever big enough to keep markets consistently trending upward. The final section of this article will dissect that productivity wild card; this section is about the drag.

1. Rates: Floor in/Ceiling out

The Fed can still tweak policy, but the structural down-trend is gone. Core inflation has migrated from “kill it at any cost” to “manage it but live with 2-3%.” That pins the risk-free level higher, leaving limited downside in yields and plenty of room for upside shocks (think supply-chain hits, fiscal sprees, or geopolitics).

Why it matters:

- Multiple math flips. A one-point rise in the discount rate shrinks the real net-present value by about 15% for a 15-year cash-flow stream. The era of “rates fall/price-to-equity ratio expands” is over.

Financing edge erodes. Big-cap balance sheets that refinanced at 2% now face 5% rollovers; leveraged buyouts will need real operating alpha to generate the same returns.

2. De-Globalization: The Tariff Tax

Import penetration and trade openness peaked pre-COVID, sagged during the pandemic, and are now fighting uphill against tariffs, export controls, and “friendshoring.” The political consensus has shifted: national security and industrial policy trump lowest-cost sourcing.

Impact on earnings:

- Margins compress. Re-shoring higher-wage labor and duplicative supply chains add costs, exactly the opposite of the 1990-2015 offshoring boom.

- Top-line hits a wall. Foreign sales delivered >50% of real revenue growth for multinationals in the last decade; fresh demand from China or India will not offset a tariff regime that taxes every incremental unit.

- FX tailwind reverses. If the dollar stays structurally strong (capital magnet + higher rates), currency translation gains flip to drags.

3. Sector Mix: The “Tech-ification” is Priced In

Software and services were <15% of the S&P in 1990; today they hover above 30%. The easy compositional lift, shuffling capital from low-ROIC assets to high-ROIC code, is largely complete.

- The market already trades at a weight-adjusted EBIT margin north of 15%, double 1980s levels.

- A further shift can’t double that again without cannibalizing the very tech margins investors are paying for.

Old-economy sectors (energy, materials, industrials) may gain share on capex re-shoring and commodity cycles, exactly the opposite mix investors have been trained to expect.

4. The Composite Drag: History Says “Lower”

When we run the same decomposition from section 1 in reverse (holding rates flat, globalization neutral/negative, and sector mix static), expected equity returns revert toward high-single digits before valuation risk. Compare the last 40 years to the 40 before 1985 (a period of generally rising rates, swings in global trade, and without major sector shifts), and you get a sense of what a more normal period can look like.

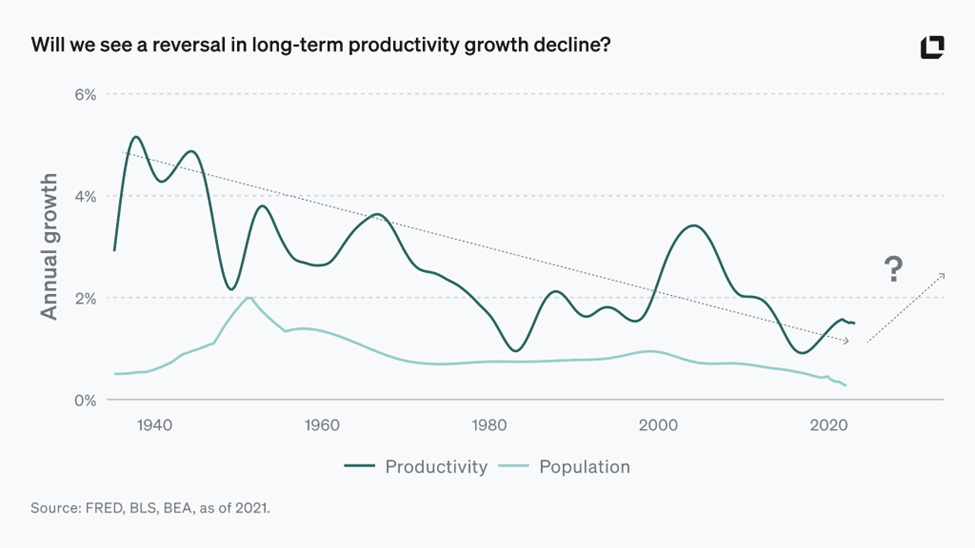

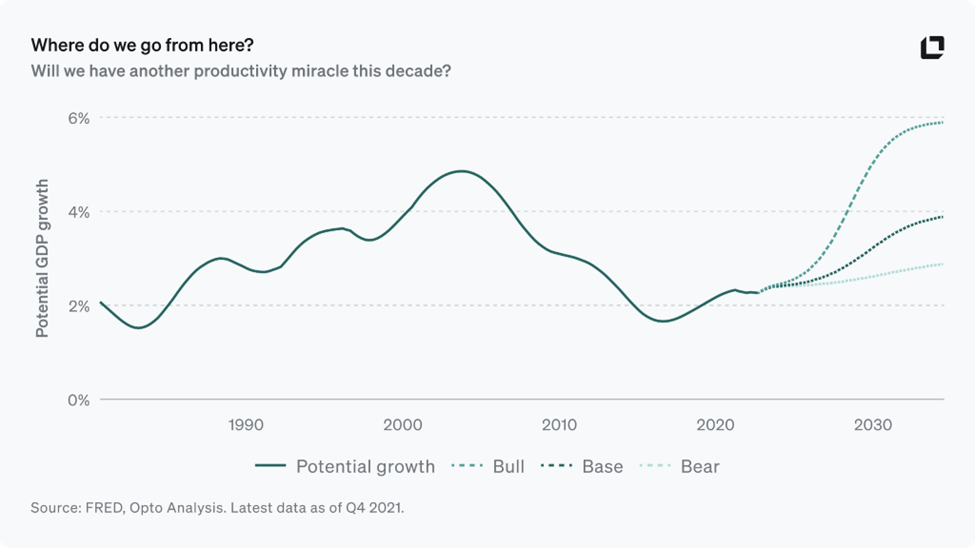

5. Productivity: The Only Escape Hatch

So, the multi-trillion-dollar question is whether the next technology wave can raise real output per worker fast enough to counter higher capital costs and fatter operating expenses. Artificial intelligence is the prime candidate, but its adoption curve, sector elasticity, and model quality remain open questions.

In the final section, we’ll quantify three scenarios and spotlight where the opportunity and alpha may hide.

Easy mode is off. Zero-rate gravity, cheap global labor, and a structural tilt toward software each handed investors free beta for decades. The next cycle charges rent on all three fronts. Portfolios built on yesterday’s macro physics need a rebuild: higher discount rates in models, lower long-run margin assumptions, and a premium on managers who can manufacture productivity rather than wait for it. Buckle up; the tailwind decade is history.

AI: Miracle, Mirage, or Middle Ground?

Looking forward, rates won’t bail you out, globalization is rewinding, and the “software-eats-everything” trade is fully digested. That leaves one valve big enough to re-pressurize growth: an increase in raw productivity. Today, all eyes are on AI to drive this upward shift. The question isn’t will AI matter (it already does); it’s how much and who pockets the surplus? Will AI gains be limited to a small set of companies and players, or will traditional industries be transformed from the base up?

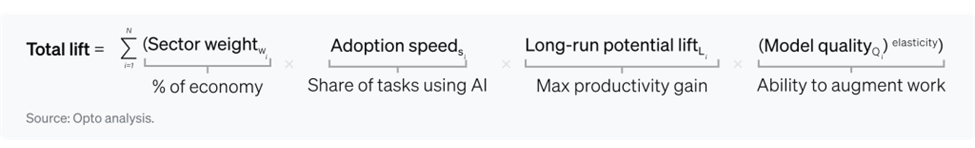

1. The Math Behind the Hype: A Four-Factor Model

To move from vague slogans to hard data, sector-level productivity uplift is a function of:

- Weight in GDP (a tiny sector won’t move the needle)

- Adoption speed (how fast firms deploy new tools)

- Maximum lift (the efficiency gap between legacy process and AI-augmented process)

- Model quality × work elasticity (how well the tech maps to tasks and how automatable those tasks are)

A basic formula:

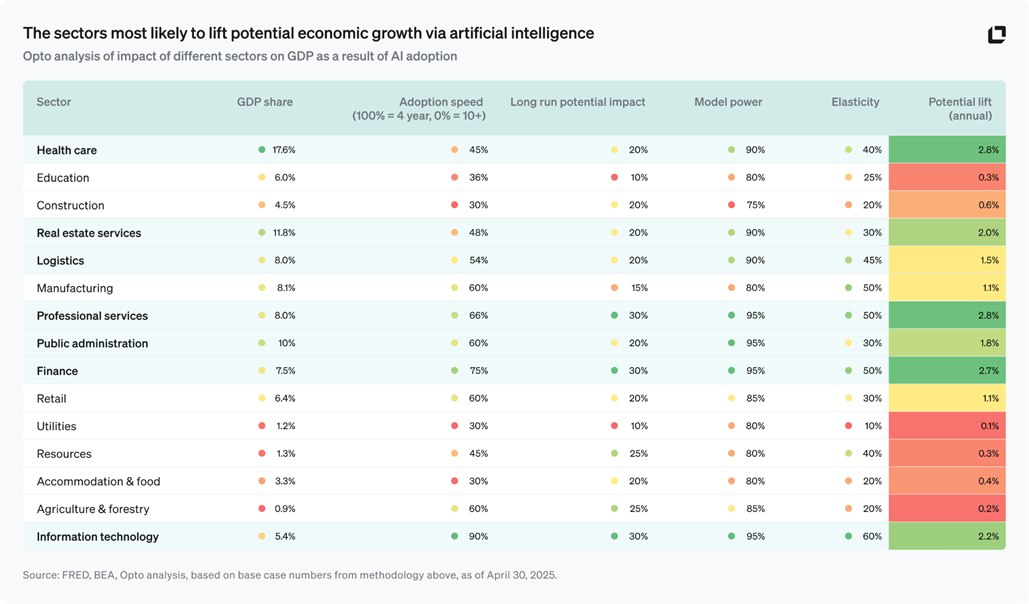

Plug in those variables across the 14 major U.S. industries and you get a real set of outcomes. I’ve highlighted some of the sectors we at Opto are watching most closely. While not every one flashes green across the board, the right confluence of factors could lead to meaningful positive shifts. While health care is likely to be slow to adopt AI, a big GDP share, already powerful models, and relatively elastic work (advanced diagnostics, hospital billing, and patient record management are all well suited to augmentation), the impact here could be meaningful to the economy and to people’s lives.

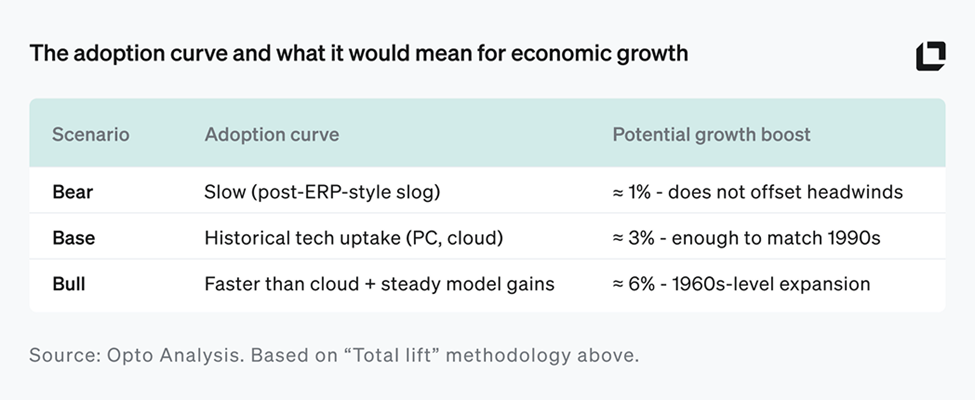

2. Three Scenarios, One Economy

Key observations:

- Boring AI will need to lead the charge. Diagnostics, billing automation, permitting automation and route optimization have gigantic dead-weight losses ripe for elimination. Transformation in sectors that have been productivity laggards will have more total-economy impact than high tech.

- Consumer services lag. A robot can’t pour your latte (at least with any flair) - elasticity is low.

- Model quality compounds. Even linear improvement in LLM accuracy can drive exponential task coverage when elasticity is significant (roughly >20%).

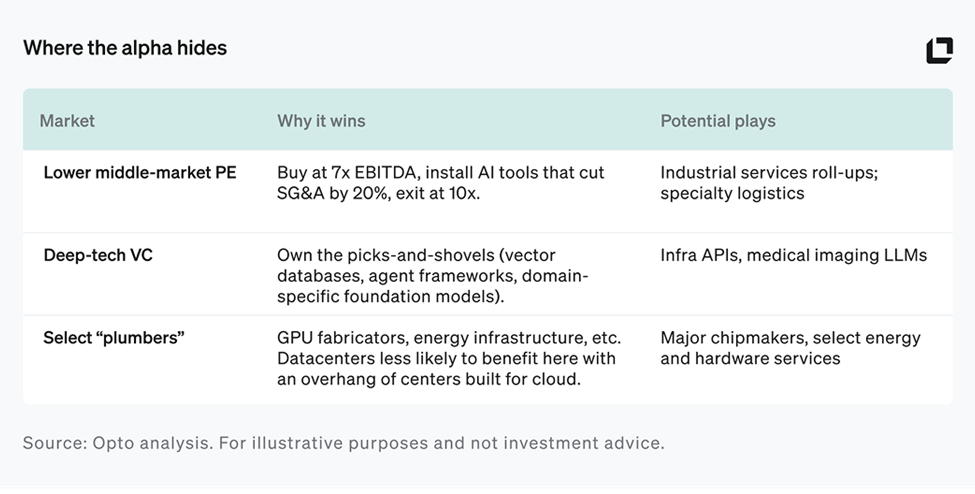

3. Winners, Losers, and the Capital Stack

Getting a bit more specific with our expectations… Legacy, ops-heavy businesses are first in line to bank margin. Hospitals, regional trucking firms, title & escrow shops (sectors with fat selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses and thin tech stacks) will add 200-400 bps of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) faster than the market expects. Large-cap public incumbents? They foot the bill. AI rollouts show up as capex and opex long before they juice EPS. Think 1990s telcos wiring for broadband—cost today, payoff tomorrow.

- Raise the hurdle rate. With real rates >1%, capital is scarce again. Demand ≥15% IRR on any AI investment—or pass.

- Favor operators over allocators. In private equity or public markets, back teams that run businesses, not just finance them.

- Barbell your exposure. Own a core of infrastructure facilitators plus high-operator PE and VC; trim the megacap middle that must both spend and defend share.

- Monitor the adoption KPI, not the headline. Track GPU burn, AI-driven cost-per-unit, and cycle-time reductions—those foretell earnings revisions.

AI is neither savior nor snake oil, it’s a force-multiplier. At full throttle, it could push U.S. potential growth back to 6%, neutralizing the interest-rate and de-globalization drag. At half throttle, it keeps us muddling along at 3%. At quarter throttle, markets face math they haven’t seen since the 1970s.

The macro stage is set: tailwinds gone, headwinds mounting. Your edge now lies in picking the operators that can weaponize AI faster than their cost of capital rises. And many of the most exciting operators are wielding or being funded by private capital.

Miss this shift, and no spreadsheet heroics will save your performance.

About the Contributor

Opto co-founder Jacob Miller serves as Chief Solutions Officer, spearheading initiatives for Opto's partnerships and the systemization of institutional-quality private markets investment techniques and programs. Before co-founding Opto, Miller spent nearly five years as an investor at Bridgewater Associates.

Miller has a passion for sensible long-term investing, systematizing investment processes, and distilling complex market dynamics into clear, logical linkages that help people better understand their investments. Having managed money for family and friends since he was 16, Miller is a certified market junkie. While he has a background in macroeconomics and high-yield debt, he finds the challenges and opportunities in the private markets space far more interesting and important, both for investors and society.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/