By Richard Sanders, CFA, Lead Asset Manager at Lifetri & Andreas Rothacher, CFA, CAIA Head of Investment Research at Complementa AG

Asset allocation aligns investment outcomes with intended results, and getting this right is a primary focus for allocators. A thoughtfully designed asset allocation process is essential. Although allocators can rely on tried-and-tested processes and best practices to perform asset allocation for liquid asset classes, these cannot be applied indiscriminately to alternative (and often illiquid) investments. These challenges were addressed in Strategic Asset Allocation: Practical Considerations for Alternative Investments. In this companion article we focus on defining asset allocation building blocks for private markets. We will also cover portfolio implementation and defining mandate guidelines for managers and CIOs.

Alternative investments are inherently diverse and heterogenous, and it is often hard to capture their relevant risk and return drivers into single, monolithic asset classes. Implementation matters compound the heterogeneity: it is not possible to get a representative slice of an idealized sub-category, and every fund manager will naturally create biases in their portfolio that make it differ from the average of the (sub-)category.

Some of these challenges are driven by the fact that private market asset classes often have no generally accepted representative benchmarks. In liquid markets, established benchmarks such as the S&P 500 or MSCI World, help allocators to define asset classes, as they have a defined index methodology and clear rules on what is included in the index. Private markets are constantly evolving, and new sub-asset classes might emerge that are not captured by the current asset classes and their respective benchmarks. We will show that defining building blocks is ultimately about making a choice between the asset allocators[1] having a larger say in the outcome or delegating more power and responsibility to investment managers that either make the investments themselves or select funds and asset managers. For both approaches we provide practical suggestions on how to thoughtfully structure the allocation process, with the aim of building an alternatives portfolio that most closely aligns with the outcome of the allocation process.

Defining buildings blocks: starting point of the allocation process

There are many asset allocation approaches. However, every allocator must face the question of how to define building blocks of the asset allocation. Sophisticated approaches rely on concepts such as risk factors or other intrinsic properties embedded in traditional asset classes. In this article, we take asset classes as our starting point, as most readers are familiar with those, but our lessons are broadly applicable in whatever way allocators like to slice and dice their investment universe. We use private equity as a leading example to highlight our remarks about granularity within an asset class: The distance between the overall risk and return drivers of the asset class can be very remote from the characteristics of the eventual portfolio the investor holds. These often contain several funds containing 10 to 15 individual firms each and, collectively, may lack a common theme that would facilitate categorization into a sub-asset class.

Allocators in the driving seat

When allocators define what asset classes and sub-categories are included in the investment portfolio, as well as the corresponding target weights, it is essential to have a clear view on how to categorize and distinguish the various sub-asset classes. Private equity is commonly sub-divided into buyout, venture capital, and growth investments. Buyout, for instance, can be further categorized by market capitalization (e.g., small cap, middle-market, large cap). However, that categorization may not necessarily align with risk and return drivers that are relevant for the institute. For instance, a healthcare insurer that focuses on MedTech may naturally be more interested in the healthcare segment, irrespective of whether it is in the buyout or venture subcategory. Our first recommendation, therefore, is to create and maintain investment cases that reflect this choice.

Preliminaries: Making investment cases – a living document that serves as a lodestar for allocation

The investment case is a document specific to an asset class – private equity in our example – that captures all relevant characteristics that are deemed to be stable enough over time to match the horizon of the asset allocation.[2] The investment case has many uses, and one of them is to identify building blocks within asset classes. To do that effectively, it should be clearly identified what asset-class-specific risk and return factors are relevant for the institution. It is essential to keep updating these investment cases regularly to reflect the evolution of asset classes. For instance, the rise of the private equity secondaries market unlocks new opportunities and should therefore be evaluated in the investment case. We suggest linking these decisions with one’s own investment beliefs.

We also recommend the rigorous exclusion of sub-categories that do not tick sufficient boxes. As we will discuss in more detail below, it is time-consuming, challenging and potentially counterproductive to include (too) many sub-categories in the allocation process. Errors of commission, in the form of investing into asset classes with a poor fit with financial goals and constraints of the investor, are expensive mistakes. It is costly and time-consuming to get access to sufficient expertise to make the investment, and potentially costlier to exit once it becomes clear the investment was ill-conceived.

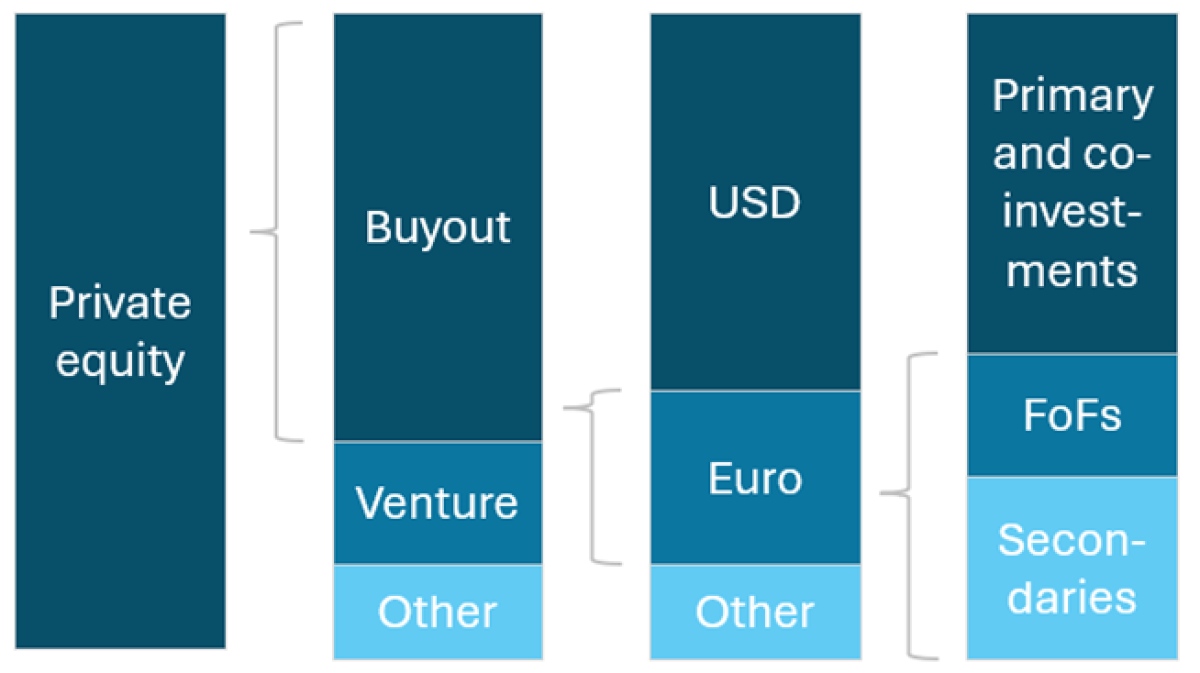

The infographic below exemplifies the aforementioned by showing a choice tree to arrive at a sensible definition of (sub)asset classes. The starting point is a euro-based investor who wishes to invest in private equity but has limited experience with manager selection and seeks a relatively stable return pattern. Currency hedging is seen as inaccessible, and they wish to invest in asset classes with a long-standing track record. Therefore, it makes sense to focus on buyout strategies as a first step and restrict the investment universe the eurozone. As a last step, primary investment and co-investments can be ruled out, as they either require in-house manager selection skills or the adequate monitoring of the outsourcing of manager selection, both of which the investor may find challenging. Fund-of-funds (“FoFs”) and secondaries may ultimately provide private equity exposure with the largest diversification and dispersion.

Chart 1: Schematic Choice Tree - Defining Sub-Asset Classes

Practical guidelines for asset allocation

Every allocation process requires forming risk and return expectations. The two most common methods we see are measuring returns from the time series of diversified indices with sufficient history (commonly more than 20 years), or using the return expectations of traditional (often liquid) equivalents and adjust them for costs, leverage assumptions, the additional return from value creation, etc. External managers and front-office investment staff can provide useful inputs and data on alternative asset classes.

If allocations are too granular, allocators run the risk of ending up with sub-categories that are very similar to each other and might, therefore, be highly correlated. In this situation, the resulting asset mix is (too) highly dependent on uncertain return expectations. If, on the other hand, asset classes are defined too broadly, the realized investment returns and risks might deviate strongly from the expectations formed during asset allocation. As a rule of thumb, an alternative asset class should be defined broadly enough to include enough investments with similar characteristics and allow for a selection within the asset class. At the same time, asset classes must be defined in a way that they do not overlap with other asset classes. We encourage investment professionals to include qualitative assessment to demarcate overlap beyond traditional measures of correlation.

A risk that should be guarded against is the creation of hypothetical portfolios that are uninvestable because managers do not find enough suitable investment opportunities. Promoting a culture in which managers can give candid and timely feedback mitigates this concern, as well as a timely update of the asset allocation when the current one is not sufficiently feasible.

Empower decision-making of the investment manager

In contrast to the previous section, this approach to asset allocation is deliberately high level, and decision-making about sub-categories (together with other relevant implementation matters, such as manager selection) is delegated to the investment team. When it comes to the leading example of investing in private equity, asset allocation could stop at setting the target allocation and bandwidths to private equity. Investment managers are well-suited to take it from there: by utilizing their own resources and through regular contacts with asset managers, consultants and other market participants, they should be in a good position to identify where relative value lies. A shortage of capital to finance companies that increase business productivity through AI? In the approach of last section, this may fall into the category venture capital, North American buyout, or even infrastructure equity. Each will have an associated target allocation and bandwidths, and that could be restrictive. If decision-making is delegated to the investment staff, they do not need to wait for an update of an asset allocation to ensure there is room available to allocate to whatever specific category the current market opportunities fall into. Just as this approach enables investors to capitalize better on current market opportunities, it can also guard against continuing to allocate money into frothy or bubbly segments. At the time of writing, public credit spreads are historically tight, and private markets have largely followed that trend. Investment managers are in a better position than allocators to decide whether it is a good moment to stand back for a while and pursue other opportunities.

The risk of this approach is that investment managers have so much freedom that the eventual investments will stray far from the intended strategic asset allocation, or they might accumulate tilts and biases that are not desirable from a diversification perspective. Investment managers are usually experts in particular asset classes, and their domain of influence usually does not reach beyond that. For this reason, allocators are best positioned to put guardrails in place that ensure the total portfolio is sufficiently diversified. Therefore, we recommend that allocators and investment managers agree on mandates that clearly identify the level of freedom investment managers have. To do that effectively, we recommend maintaining updated investment cases that clearly delineate the drivers of risks and returns and structuring the mandate along the same lines. For private equity, for instance, it is common to observe significant dispersion between returns of individual investments, and certain sectors can provide outsized returns in the right environment. Depending on the level of confidence the institute has in selection and timing skills of the investment staff, the mandate guidelines can enforce lower or higher levels of diversification over individual firms and sectors. In this way, allocators can still retain control over the high-level properties of the overall portfolio. Said guidelines also make performance attribution and ongoing oversight easier.

Finding the right balance

Most investors will not be on the extreme ends of the spectrum that ranges from full empowerment of allocators or investment managers on the other side. A discussion with the different stakeholders should help to balance profiting from investment opportunities within an alternative asset class and the need for proper diversification (to avoid asset class overlap), oversight, performance measurement, and investment controlling. It is also crucial that investment managers understand the overall investment goals of the allocator and how the manager’s asset class or vehicle are used in a portfolio context. We see it as central to the role of the CIO to decide which investment decisions are made by allocators and which are made by investment managers. We recommend regularly reviewing this and ensuring that the organization is adequately equipped (e.g., staffing and knowledge) to follow the chosen model. The decision of what to insource and what to outsource should also be part of this discussion, too. Outsourcing tasks also implies a clear procurement process as well as defining quality standards, service agreements, and guidelines. Defining these for external parties may also help define rules and expectations for internal service providers. Creating the aforementioned guidelines for internal teams, when previously no such guidelines were in place, can demand time and diplomatic skills from the CIO or board.

Conclusion

Investors must ensure that they find the right granularity when defining alternative asset classes. This will be crucial to maintaining portfolio oversight while still capturing new investment opportunities that emerge within alternative asset classes. This dilemma also emerges when defining investment guidelines for investment managers. An open dialog between the board and the investment manager, as well as feedback mechanisms, help to align mandates. It is also crucial that investment managers understand the overall investment goals of the allocator and how the manager’s asset class or vehicle are used in a portfolio context.

In a second, forthcoming article we’ll take a closer look at how the illiquidity of many alternative asset classes impacts allocation decisions…Stay tuned.

About the Contributor

Richard Sanders is an experienced asset allocator focusing on fixed-income portfolios for institutional investors. He advised sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and insurance companies on manager selection and asset allocation and managed the liquid investments of insurance firm NN Group. He now heads the asset management activities at Lifetri, a specialist insurance buyout firm that focuses on investments in private markets.

Andreas Rothacher is the Head of Investment Research at Complementa AG. In his role, he advises institutional clients on strategic asset allocation and manager selection. In addition, he is a co-author of Complementa’s annual Swiss pension fund study (Risk Check-up). He is also the author of various articles and publications. Andreas is the Chapter Head of the CAIA Zurich Chapter and a member of the CFA Swiss Pensions Conference Committee. Before joining Complementa, he worked at a German family office and held various roles at UBS and Credit Suisse.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/

[1] Those who ultimately make the decisions on asset allocation: e.g., an investment committee, board of trustees, management of the investment company.

[2] Investment cases sit usually alongside investment policies where the latter focuses on general investment principles tailored to the needs of the investor and are not specific to any asset classes or actual investments. For instance, investment beliefs, or long-term financial goals, would typically be found in the investment policy.