Preqin, the multi-national data and consulting firm, in its newly released 2013 “Global Alternatives Report,” offers a good deal of news about asset allocation, especially in connection with private equity on the one hand, hedge funds on the other. It also offers a list of questions for investors doing their due diligence – questions proposed specifically in a PE context but many of which will be appropriate in either context.

Preqin, the multi-national data and consulting firm, in its newly released 2013 “Global Alternatives Report,” offers a good deal of news about asset allocation, especially in connection with private equity on the one hand, hedge funds on the other. It also offers a list of questions for investors doing their due diligence – questions proposed specifically in a PE context but many of which will be appropriate in either context.

The list comes courtesy of a contribution to the report from Stephen Cravens, the head of fund analytics for Cogent Partners. The first round of questions he proposes includes these:

- What kinds of companies have you bought and sold, and at what multiples?

- What happened to the acquired companies fundamentals when you did so?

- [If the PE fund has strong performance numbers], are they founded upon one recent home run, or a consistent record of well-hit singles and doubles?

- What is the process by which you generate your investment ideas?

Cravens then tells investors they should assimilate all the data they receive as a consequence of asking such questions before the next round. This next round involves asking the PE for investment memos. Also:

- Which firms do you see as your closest competitors?

- How many of your limiting partners do you expect will re-up?

- Does the GP have skin in the game?

- Are there any side letters that put other investors on a footing better than that available to me?

Also, he says, interview portfolio company executives, intermediaries who were involved in recent transactions involving this PE fund, and current or former limited partners.

The Learning Curve for Institutions

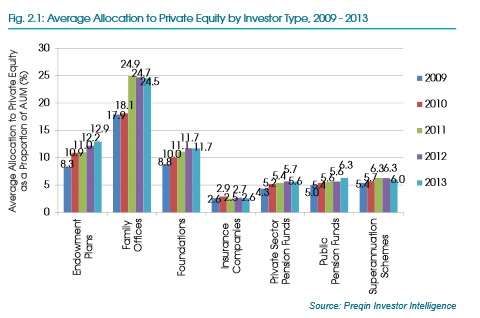

As the graph below indicates, many types of institutions have increased their exposure to private equity in particular in recent years. Family offices (represented by the second set of bars) had 17.9% of their assets in private equity in 2009. That amount rose dramatically into 2011, peaking at 24.9%, and although it has declined a bit since it is almost seven points above the 2009 level.

Endowment plans (the first set of bars) show an unbroken upward slope. They allocated only 8.3% to PE in 2009, and that exposure is now at 12.9%.

The pattern with respect to allocations to hedge funds is somewhat different from that of allocations of PE. As Preqin’s report explains, many institutions have long been familiar with hedge funds, their learning curve has flattened out so to speak, and they have established a target allocation for hedge funds considered as an asset class. In this situation “their current allocation then fluctuates around this based on market conditions year to year and the movement of an investor’s capital.”

For example, endowments were 18.8% exposed to hedge funds in 2009, and are again 18.8% exposed to hedge funds in 2013. The highest level of exposure in the intervening period was 20% in 2011.

Family offices had a 16.8% allocation to hedge funds in 2009, went to 19% the following year. They are still working within roughly the same range. They were 16.6% exposed in 2012 and are 19.1% exposed in 2013.

But not all institutions appear to be circling around some established equilibrium with regard to hedge fund allocations. Pension funds, both the private sector and the public sector species of this genus, may still be in a phase of becoming comfortable with hedge funds, acquiring experience. Both have been increasing their exposure over this period of years.

Assets under Management and Exits

The PE industry’s AUM has continued its growth in the years since the global financial crisis. There was some flattening out in the rate of growth in the period of 2007-08 itself, but that is from the market’s perspective a distant memory now.

One tricky post-crisis reality for those who invest in PE, though, is that the crisis resulted in a sharp fall in distributions/payouts to investors in these funds. In 2207, distributions were at $345 million. That number dropped the following year to just $143 million. It wasn’t until 2011 that the distributions exceeded the 2007 level.

“With lower exit levels” Preqin says, investors have less capital to invest in new funds, “leading to a far more competitive fundraising environment.”

Another section of the report, written by Pius Fritschi, managing partner, LGT Capital Partners, discusses “the myth and reality of hedge funds’ performance and costs.”

One of his points is that Basel III and other regulatory changes have been pressing banks and insurance companies to sell certain of their assets in order to divest themselves of the accompanying risks. This represents an opportunity for the hedge funds that can offer to buy those troublesome assets.

“In many cases, these are very complicated investments “ such as insurance-linked securities or securitized commercial loans, he says.

One’s instant response might be to say, “Aha! But the banks are getting rid of these assets because they are risky. Thus, the buyers are suckers and the whole regulatory exercise is a test of the biggest-fool theory.” But Fritschi reminds us in this context of Portfolio Diversification 101: what doesn’t work in your portfolio may make perfect sense in mind. Hedge funds can used these insurance-linked securities and the like to increase their risk-based return.

Yes, hedge funds have recently posted lower returns than some of the equities markets. That’s hardly a reason to give up on them, though it is a good reason to be strict in one’s due diligence: an observation that brings us back to where we began.