Benoit Guilleminot and two colleagues have written a working paper on the impact of index flows on commodities prices, using U.S. traded (agricultural) commodities as their database. Along the way, they encourage thought about the nature of cause and effect in finance.

There are many uses of terms such as “cause.” Sometimes, we use the word to refer to something that is happening at the same time as its effect. As the wind moves through the trees the leaves rustle. As the water rises and falls in the ocean in a wave pattern a surfer slides toward shore.

At other times though, we use “cause” to refer to an event that clearly preceded its effect in time. One pool ball hit another and stopped: the second ball then moved forward. Penetration by a bullet caused the victim’s death.

It is this second more time-specific sense of causation that has encouraged the notion of “Granger causality.”

Derivatives and their Underlyings

In May 2008, Michael Masters , a portfolio manager himself, testified before the Homeland Security Committee of the U.S. Senate and maintained that a new class of institutional investors had skewed commodities futures markets, causing a rise in the prices not only of the derivatives but on the underlyings. He called the new class of investors the “index speculators,” because their strategy is to allocate across the 25 key commodities futures covered by the most popular indices.

There certainly was a run-up in both commodities index flows and commodity prices during the two year period preceding Masters’ testimony. But a number of authors have produced other explanations of those twin run-ups. Perhaps the most obvious alternative explanation is that the rise in prices invited the speculators to move into the indexes, and that Masters simply had reversed the causal arrow.

One of the important bits of economics’ jargon here is “Granger causality.” One fact “Granger causes” another if it reliably precedes that other. Granger causality isn’t the same thing as real causality. A virus may infect a human body and cause a variety of symptoms in a certain dependable sequence. The early symptoms then reliably forecast the later symptoms. This doesn’t mean that the early symptoms cause the latter symptoms, that the cough causes the rash. Nonetheless, we would say that the cough “Granger causes” the rash.

Granger causality can be an important though non-decisive clue to full-throated, before-therefore-after causality. If a rise in a certain type of speculative flow preceded the rise in commodity prices, it would support the hypothesis that the one caused the other.

A Misleading Clue

Guilleminot and his colleagues, Jean-Jacques Ohana and Steve Ohana, think that on this issue Granger causality has been a misleading test. They acknowledge that most studies fail to show any Granger causality, any forecasting of price changes by index-oriented flow. [We discussed a study making a related point here in October 2011.]

But they also contend that the relationship of index flows and commodities prices is not a before-and-after sort of causation. It is a contemporaneous relation. Think of it as akin to the relationship between a wind passing through the trees and the rustling of the leaves. Both events occur at the same time, so neither predicts the other. Neither can be said the “Granger” cause the other. Yet common sense tells us that the wind causes the rustling of the trees, not the other way around.

Source: Guilleminot et al., The Interaction of Hedge Funds and Index Investors in Agricultural Derivatives Markets

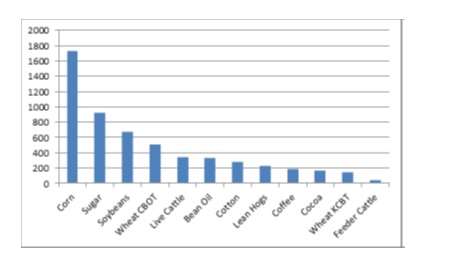

For twelve agricultural commodities traded in the U.S., the CFTC releases trading breakdowns on a week by week basis in terms of three well-defined categories: commodity index traders (or CIT); commercial non-CIT; and non-commercial non-CIT.

The non-commercial non-CIT component are those Guilleminot and et al call, for short, hedge funds. The commercial non-CIT is the Main-Street hedger: “buyers, processors, physical traders and producers that mostly use derivatives markets for the purpose of hedging commodity price risk.” The first group, the CIT traders, are those whose weight in the market worried Masters.

Trend Following

The twelve categories are listed along the X axis of the above graph, presented in order from the commodity with the largest average open interest in thousands of lots (corn), to the one with the smallest average open interest (feeder cattle.)

Source: Guilleminot et al., The Interaction of Hedge Funds and Index Investors in Agricultural Derivatives Markets

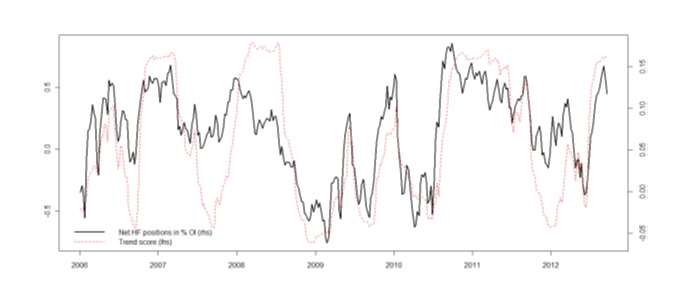

Another graph in their paper, also shown here, displays the moving positions of hedge funds in the corn market, as the black line. The red line results from a “smooth momentum indicator” these authors have created to characterize the average net positioning of trend following systems.

The two track each other to a marked although of course an imperfect extent. It is so marked a correlation that the authors conclude that “the trend following strategy is indeed very representative of the aggregate positioning of hedge funds in agricultural derivatives markets.”

That leaves a very real possibility that there is a contemporaneous cause and effect, relationship, that the entry of a lot of index investors causes to the entry of trend-following hedge funds, and together they have caused a significant increase in the price of corn.