Microsoft has now announced a phase out of its long-term workhorse browser, Internet Explorer, in favor of its Project Spartan.

Microsoft has now announced a phase out of its long-term workhorse browser, Internet Explorer, in favor of its Project Spartan.

One generation’s revolutionary disruptor is the next generation’s senile establishment, and MS is desperately trying to reinvent itself after running through that whole gamut from its 1986 IPO to the present. Some corporations do manage that feat, discovering their own fountain of youth and becoming a disruptor again. I wish Microsoft well in that endeavor, of which Project Spartan is a part.

But the demise of MSIE reminds me of the intensity of the browser wars of the 1990s, a time when a considerable body of public opinion held that Bill Gates was evil incarnate, and that he was doing Netscape and its browser, the Navigator, a terrible wrong.

That memory in turn suggests to me a possible formula for alpha generation that might be available even in the sedate-seeming world of public equity long positions: buy into firms against whom the Department of Justice has just brought an antitrust complaint, or opened a high-profile investigation, especially if that complaint or investigation involves illegal monopolization of an industry. Hold those stocks for a period of between six and eighteen months, during which time the original allegations will become irrelevant and perhaps even, in quickly-developing industries, quaint. Then sell.

Department of Justice Microeconomics

That has the proper counter-intuitive feel to it. Yes, the initial announcement of the legal action will surely bring some sort of downward move. But that may be as transient as many other announcement-driven moves.

What should be more worrisome is the fact that a company has reached the level of success that typically draws that kind of unwanted attention from the D of J, which may to some suggest that the market has fully realized its value. Won’t an investor buying then run a great risk of buying at a top?

Maybe. But the more intriguing possibility is that the D of J typically brings these high-profile actions by piling its legal theories on top of an ill-fitting microeconomic hypothesis (a hypothesis no doubt whispered into the Department’s ears by the market participants who are losing out to the alleged monopolists.) Buying the defendant may be one way of betting that the government lawyers have their economics wrong: which sounds like a good hunch to play. I hope to get some heavy-duty number crunchers engaged in testing this proposition. The numbers below may serve merely as an inducement, a call to bring up heavy artillery on this front.

Specifically, the death of the MSIE suggests two tests for this hypothesis: one from the prehistory of the Browser Wars, the other from the thick of those Wars.

In August 1993, before the Wars got underway, Justice opened its investigation of whether Microsoft was abusing its control of the operating system market. The worry was that a monopoly in market A can be leveraged into a monopoly in market B by a merchant of A who makes a take-or-or-leave it offer to customers, "take our B along with our A or we won’t let you buy either."

In this case, the allegation was that MS, having established operating system dominance for Windows, was using it to control various applications of that system. [Internet browsing was not yet a key issue.] In July, 1994, the Justice Department and MS reached an accord. MS agreed to play nice in various markets relating to its own OS. This is the settlement that became the basis of Netscape’s anti-MS arguments later in the decade.

So this is our first test. Suppose you had invested in Microsoft just when the Department of Justice began this investigation in the late summer of 1993.

You would have bought the stock at $2.41 (split-adjusted closing price on August 23, the first business day after the start of the investigation.)

Yes, you would have had to ride out an initial drop from that point. A week later, the stock price (considered on the same basis) had fallen to $2.27. But that was the whole of the drop. And it represented just 5.8% of the share value. Movement the following week was up.

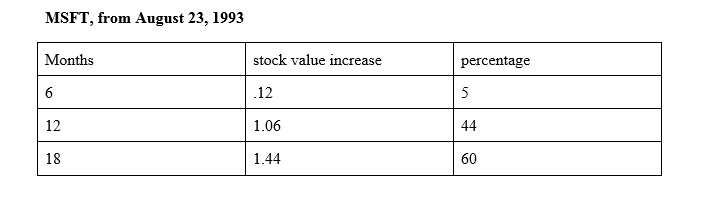

Let’s not get too long-run here. Let’s just look at the split-adjusted price six months, 12 months, and 18 months out from the hypothetical purchase date of 8/23/93. The percentage gain in stock value for each of those periods is in the above table.

The Browser Wars Proper

A district court judge approved the above-described settlement in August 1995. By that time, browsers were big news. Between the time the D of J investigation of MS’ tying practices began, and the time of that 1995 consent decree, Netscape had refashioned the world with its “Navigator,” the first truly mass market browser. There was much talk about how the OS was going to become irrelevant, a mere “toaster.” It was in this context that MS, unready for mere bread-warming service, introduced its IE.

The first two versions of IE were generally considered inferior, and no threat to Netscape. It was only with the release of IE 3 (1996) that MS showed it was sufficiently good at this to challenge Netscape. Further, as a legal matter it wasn’t obvious that MS was acting in defiance of the ‘95 court order. This question turned on how easy or difficult it would be for consumers to uninstall IE 3 and replace it with Navigator or something else. MS of course argued in the inevitable litigation that this was easy and, thus, that the 1995 order shouldn’t be construed so as to tie MS’ hands against Netscape.

So: back to court. On October 27, 1997, the Justice Department filed a lawsuit demanding that MS be fined $1 million a day for allegedly violating the ‘95 decree by bundling the IE 3 with the Windows ‘95 OS.

Our Second Test

Mr. Market seems to have been remarkably unconcerned about this lawsuit from the start. MSFT closed that day, a Monday, at $16.11. A week later, November 3, it closed 4% higher, that is, at $16.77.

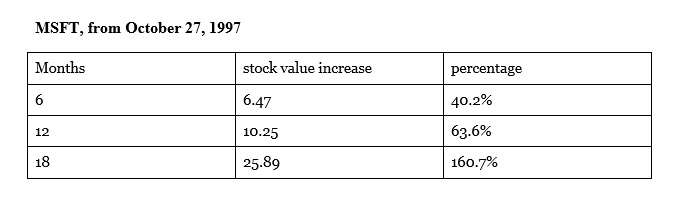

Let’s use the same intervals as before: six, 12, and 18 months, and stick with the adjustment for splits. The resultant table looks like this:

In both cases, a strategy of betting that the Justice Department’s case would unravel have served an investor quite well.

But these are preliminary thoughts, and my only hope for them is that they will draw further research.