In February of this year, the Economist Intelligence Unit surveyed 200 senior asset managers and institutional investor executives to learn what factors are most important in the way they make their decisions. Several different types of institution were involved, including hedge funds, private equity firms, insurance companies, and nonprofits.

Also, there was a great geographical spread represented in the sample, with 60 respondents each from North America, the Asia-Pacific region, and Europe, the remaining 20 from the Middle East.

In terms of the size of the institutions involved: half manage assets of $5 billion or greater, the other half manage less than that.

The EIU/Northern Trust white paper that results from this survey begins with the observation that alternatives [which it defines broadly to include hedge funds, infrastructure, natural resources, private equity, real estate, and funds of funds] have now been thoroughly mainstreamed.

Top Investment Considerations

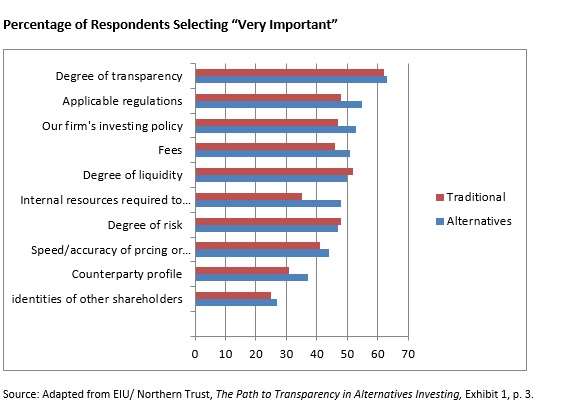

The top investment considerations for survey participants, and the difference in this respect between traditional and alternative investments, are indicated in the graph below.

The obvious takeaway from this graph is that the degree of transparency is easily the standout demand addressed by investors to either sort of manager. Among investors in traditional funds, degree of transparency is one of only two demands considered “very important” by more than half of the respondents, sharing this honor with degree of liquidity.

New Business Models – and Transparency

The 2008 global financial crisis of course had a negative impact on the alternative investments industry. But the asset class survived, and in the words of the World Economic Forum, quoted by the EIU, the asset class “emerged stronger and more important to stakeholders than ever before.”

New business models have arisen to supply demand across the spectrum of investors, including those investors eligible for and interested in alternatives. Publicly traded limited partners are one important example. Further, legislation such as Dodd-Frank (in the U.S.) and the AIFMD (in Europe) have re-assured investors that there are watchdogs in the world of alternatives, that it isn’t as complete an authority-free zone as it has sometimes been made out to be.

The paper quotes Sarner Ojjeh, a principal at EY Wealth and Asset Management, who says that when the crisis of 2008 hit, “institutional investors were caught unprepared. They couldn’t assess, quantify, and report on their exposure in a timely fashion. That was a big limitation … the investment boards for these organizations were not satisfied with such constraints.” Transparency has taken center stage ever since.

On some of the critical points that have to be made transparent, the report quotes William Chyz, director of asset management and client services for Westcourt Capital Corporation, an advisory firm for high net worth investors. He offers a short list: it is “important [for investors] to have a clear picture of a fund manager’s investment strategy. What kind of returns can an investor expect? Are third parties verifying what’s going on?”

Not an Unmixed Blessing

The survey looked into what sources of information investing institutions draw upon for their due diligence. “Most rely heavily,” the report says, “on specialist databases, market data feeds and reports from analysts and the media, as well as on administrator and custodial data.” There isn’t a big divide between investments in traditional and alternatives here, but one difference worth noting is that specialist databases are used less often in seeking information about alternatives.

Looking at the data by region, the survey shows that firms based in Asia or the Pacific rely to a greater degree on press and analyst reports, market data feeds, and regulatory or financial filings than do their counterparts elsewhere.

As Ojjeh observed in an interview, transparency is not an unmixed blessing. When the alternatives managers make data available they create the expectation that the institutional investors “will be analyzing the data and using it to manage exposure.” They run the risk of criticism and liability should they receive data that signals that they ‘should’ exit from a position, and then fail to act upon it.