Introduction to TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM (TKFA)

By Tanuj Khosla, CFA, CAIA, MBA

INTRODUCTION

The construction of hedge fund portfolios by institutional investors around the world has been a combination of both science and art over the years. While some use a strict quantitative methodology like Risk Budgeting and/or Sharpe Parity along with a correlation matrix among different hedge fund strategies to create a portfolio, others use more ambiguous, discretionary and qualitative factors like the in-house view on an asset class or geography (or both) to do so.

Either way a vast majority of institutional investors have been overpaying for beta that has been masked as alpha by the hedge fund manager or worse, paying for non-performance.

In this paper, we attempt to come up with a metric that helps investors keep track of how much alpha they are giving away to the hedge fund manager, both for an individual hedge fund as well as for their entire portfolio.

We call it TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM (TKFA)

Before we delve into the metric, let’s take a look on how fees paid and alpha generated are computed for hedge funds with

- High water mark

- Hurdle rate

HIGH WATER MARK

Management fee: Mf (charged annually in advance)

Performance fee: Performance fee x (Gross returns – Management fee)

Total fees paid by investor: Management fee + Performance fee

For example, if a hedge fund manager charges 2% management fee and 20% performance fee, then the total fees an investor would pay for a 10% gross return performance shall be

Management fee: 2%

Performance fee: 20% of (Gross returns – Management fee)

= 20% of (10% - 2%)

= 1.6%

Total fees paid by investor = Management fee + Performance fee

= 2% + 1.6%

= 3.6%

Net returns for the investor = Gross returns – Total fees paid

= 10% - 3.6%

= 6.4%

Alpha = Gross returns – 0% (since it is high-water mark)

= 10% - 0%

= 10%

TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM : Total fees paid / Alpha

= 3.6% / 10%

= 0.36 (36%)

In other words, the investor gets 64% (100% - 36%) of the alpha with the remaining 36% going to the hedge fund manager.

HURDLE RATE

Management fee: Mf (charged annually in advance)

Performance fee: Performance fee x (Gross returns – Hurdle rate - Management fee)

Total fees paid by investor: Management fee + Performance fee

For example, if a hedge fund manager charges 2% management fee and 20% performance fee and has a 5% hurdle rate, then the total fees an investor would pay for a 10% gross return performance shall be

Management fee: 2%

Performance fee: 20% of (Gross returns – Hurdle rate - Management fee)

= 20% of (10% - 5% -2%)

= 0.6%

Total fees paid by investor = Management fee + Performance fee

= 2% + 0.6%

= 2.6%

Net returns for the investor = Gross returns – Total fees paid

= 10% - 2.6%

= 7.4%

Alpha = Gross returns – Hurdle rate

= 10% - 5%

= 5%

TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM : Total fees paid / Alpha

= 2.6% / 5%

= 0.52 (52%)

In other words, the investor gets only 48% (100% - 52%) of the alpha with the majority of alpha of 52% going to the hedge fund manager.

Observations from the above two calculations:

For the same management and performance fees and gross returns,

- The investor gets higher net returns in case of a hurdle rate as compared to high-water mark.

- The alpha generated is higher in case of high-water mark as compared to hurdle rate.

- Since the computed alpha is smaller in case of hurdle as compared to high-water, the TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM is larger for hurdle rate as compared to high-water mark.

APPLICATION TO A HEDGE FUND PORTFOLIO

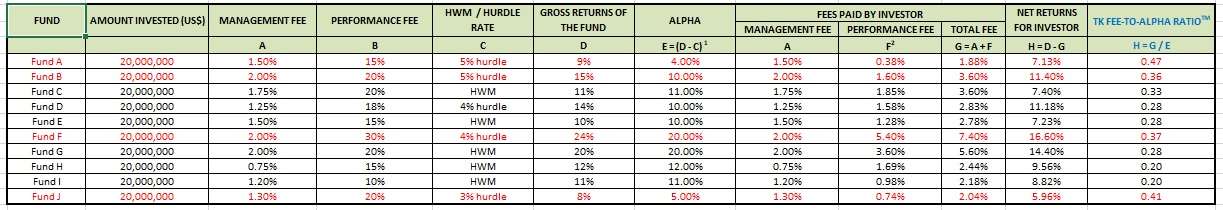

Let’s consider a hypothetical US$ 200 mn hedge fund portfolio equally allocated cross 10 hedge funds, each with different fee and hurdle/high-water mark terms. We compute the TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM for each fund as well as for the entire portfolio.

- For high-water mark, C = 0%

- We compute Performance fee using the same methodology for hurdle rate and high-water mark as shown above.

Key Observations:

- Manager of Fund A, having a relatively high hurdle rate of 5% takes 47% of the alpha generated despite generating low gross returns.

- Manager of Fund F, despite generating relatively high gross return of 24%, takes 37% of the alpha.

- Manager of Funds H & I take only 20% of the alpha but have a high water mark and not a hurdle

TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM for the entire portfolio: 0.32

In other words, the investor pays away 32% of the alpha generated to the ten managers.

DEFINITION OF ALPHA

In the current fee sensitive environment, most hedge funds have a hurdle rate as institutional investors don’t want to pay performance fees up until that hurdle is achieved. Many funds now have both hurdle rate and high-water mark.

The computation of alpha depends upon whether the fund has a hurdle or high-water mark (or both).

However both hurdle rate and high-water mark sometime can’t prevent investors paying performance fees for beta and the concept of a Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR) has been gaining some traction.

This Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR) is a mutually agreed upon and publicly available index.

For example, let’s suppose there is a US equity long/short manager with 2 & 20 fee structure and the institutional investor demands that S&P 500 is the Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR). Let us now suppose that the fund has gross returns of 26% for the year while the S&P is up 20%.

Management fee: 2%

Performance fee: 20% of (Gross returns – Variable Beta Hurdle Rate - Management fee)

= 20% of (26% - 20% - 2%)

= 0.8%

Total fees paid by investor = Management fee + Performance fee

= 2% + 0.8%

= 2.8%

Alpha = Gross returns – Variable Beta Hurdle Rate

= 26% - 20%

= 6%

TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM : Total fees paid / Alpha

= 2.8% / 6%

= 0.466 (~47%)

Some institutional investors multiply a beta with the index to arrive at the Beta Adjusted Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR). For example, in the above case if the investor decides use a beta of 0.6, then the Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR) shall be:

Variable Beta Hurdle Rate = Beta x S&P 500 performance for the year

= 0.6 x 20%

= 12%

In conclusion, the calculation of alpha largely depends on the choice of base used i.e. hurdle or high-water market. In case of the former, it can be further sub-divided into the type of hurdle to use – fixed, floating, Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR) or Beta adjusted Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR).

Choice of base to compute Alpha:

- High-water mark

- Hurdle Rate

- Fixed Hurdle Rate

- Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR)

- Beta adjusted Variable Beta Hurdle Rate (VBHR)

There is no right or wrong here and the choice of the base depends on (a) the terms of the fund (b) preference of the institutional investors(s). We can think of the Sharpe Ratio as an analogy here wherein different investors use different risk-free rates.

In conclusion, just like the construction of hedge fund portfolios, this is a combination of art and science and different institutional investors might make different choices while computing alpha.

THE WAY FORWARD

The Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRS) are implementing what they call a “1 or 30” fee structure. This fee structure is rapidly gaining the attention of both managers and investors and might very well become the industry standard in the years to come.

The purpose of “1 or 30” fee structure is to ensure that the investor retains 70% of the alpha generated by the hedge fund manager.

Mechanics of the “1 or 30” fee structure:

The structure is referred to as “1 or 30” because it will always pay a 1% management fee, which the manager trades for 30% of alpha (by way of performance fee) when the latter is greater.

The only exception to this is when an investor is catching up to its 70% share of alpha, following periods when the 1% management fee exceeded its 30% share of alpha

Management fee: 1%

Performance fee: 30% of Alpha – 1%

Total fees paid by investor: 30% of alpha

In this case, TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM is fixed at 0.30 (or 30%)

CONCLUSION

Many institutional investors have got a raw deal from the hedge funds as (a) alpha has been shrinking (b) they have been paying alpha fees for beta.

It is then nothing short of a cardinal sin if they have to pay a disproportionate share of the real alpha generated to the manager as fees. This metric enables them to keep a track of how much alpha they are giving away. As shown above, the definition (and consequently computation) of alpha can be varied and the investor shall have to pre-define that.

In the current environment, a TK Fee-to-Alpha ratioTM of over 0.3, implying that the institutional investor is paying away more than 30% of the alpha generated, is excessive and calls for attention and maybe even corrective action.

THE END

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanuj Khosla is an Assistant Portfolio Manager at a Singapore based Asian long-short credit hedge fund, He has been in the hedge funds for 8+ years and in the financial industry for over a decade. In 2016, Tanuj was named in the Top 20 ‘Most Astute Investors in Asian G3 Bonds for 2016’ by the well-known journal The Asset.

Tanuj started his career with ICICI Bank Ltd. in New Delhi, India. Tanuj holds an MBA with a dual specialization in Finance & Strategy from Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological (NTU), Singapore. He holds both the CFA and CAIA charters and is a CAIA Singapore Executive Committee member. He is a part of CFA Education Advisory Board Working Body and was recently appointed as a Curriculum Consultant by the CFA Institute.