A Guide to SPACs for Arbitrageurs, Shareholders, and Private Companies

By Keith Black, PhD, CFA, CAIA, Managing Director of Content Strategy, CAIA Association

There has been tremendous activity in the SPAC market in 2020 and 2021, a time when more than half of the IPO activity has been attributable to the issuance of new SPACs. In fact, over the last six months, the fundraising proceeds from SPACs exceeds the total issuance from 2009 to 2017. Investors may not be aware of the risks, as SPACs have lower disclosure requirements, greater dilution, and a greater ability to provide forward-looking financial statements than traditional IPOs. Some have even speculated that companies going public through a combination with a SPAC would be ready for a traditional IPO in three years, but investors are taking the three-year financial projections as fact, even though some of these companies have no revenue. According to the Wall Street Journal, “it took Google eight years to reach $10 billion in revenue, the fastest ever for a US startup." Five companies with current SPAC combinations in the electric vehicle and transportation sector currently project reaching $10 billion in revenue in three to seven years. Perhaps there is a reason that such statements are not allowed for traditional IPOs.

This post provides a primer on SPACs, helping target companies and investors alike to evaluate opportunities that come their way. Both investors and private companies targeted as business combinations should carefully consider the potential conflicts of interests, the feasibility of business plans, and total costs of the SPAC structure.

A SPAC is formed for the purpose of allowing a private company to become publicly listed. The sponsor of the SPAC is an investment manager who floats an IPO of the SPAC and seeks to identify a private company that is willing to be publicly traded. SPACs are currently a market structure in Canada, Malaysia, and the US, while Hong Kong and Singapore are investigating the structure for potential listings in their markets.

A typical SPAC floats an IPO and then aims to use the proceeds to purchase an unidentified single private company, often in a named industry sector. Once the funds have been raised through the IPO, the sponsor has a stated period, such as two to three years, to identify the private firm to be acquired and complete the business combination. Shareholders of the SPAC must vote on the business combination, with a simple majority of shares required for approval in the US and Canada, for example, and 75% required in Malaysia.

SPACs can be compared to IPOs, as each structure results in a private company becoming publicly listed. However, there are several key differences between SPACs and IPOs. First, US regulations treat SPACs and IPOs differently, as IPO underwriters are prevented from providing financial projections and forward-looking statements, while sponsors of SPACs are allowed to provide three years of financial projections once the private company has been named. The result is that the private companies targeted by SPACs tend to be younger and less proven than IPOs, and the market valuation trades more on the future potential of the SPAC rather than on the historical financials of the private firm. Second, a SPAC is likely to raise capital more quickly and easily than an IPO, as the SPAC has no financials or operating history at the time of the listing of the SPAC. Third, and most obvious, the identity of the private company and significant disclosures are available at the time of the IPO, while the SPAC has two to three years to name the private company that will become public.

SPACs also have interesting arbitrage-like characteristics built into their structure. The typical SPAC raises capital in an IPO with units priced at $10. The standard unit is a combination of common stock and warrants. Warrants are long-term call options to purchase newly issued shares of the company. In an ordinary SPAC, the warrants have a five-year term, a strike price of $11.50, and mandatory conversion once the stock price has exceeded a price of $18 over a specific period of time, such as 30 days. While listed call options give investors the right, but not the obligation, to buy shares of stock from other market participants who have sold the call options, warrants are exercised by providing capital directly to the issuing company in exchange for newly issued shares. For example, when the warrants have a mandatory conversion and the stock price is trading above $18, investors would receive newly issued shares after sending their warrants and $11.50 per share in cash to the company. The exercise of warrants dilutes the existing shareholders, as new shares are issued at $11.50 when the stock is trading above $18. Dilution reduces the proportional stake of shareholders who continue to hold the common shares and do not exercise any warrants.

When the SPAC raises capital in an IPO at $10, at least 90% of the gross proceeds from the IPO must be invested in an escrow account. The cash proceeds, which may earn interest, are held in anticipation of a business combination or the potential return of cash to shareholders if a business combination is not completed or approved within the allowed period. This escrowed cash creates downside protection for investors who hold SPACs before the business combination is identified and approved. That is, the minimum value of the SPAC should be the value of the cash in the escrow account, typically $10 per share. Returns can be positively skewed, as the stock often rallies when the merger with the private company is announced or the warrants earn significant value over time.

Due to this positively skewed return pattern, as much as 85% of SPAC shares are held by event-driven hedge funds and institutional investors before the time the private company is identified. While the downside risk is limited by the cash holdings, there can be significant upside. Adding to this positively skewed trade potential is the redemption process. At the time of the IPO, the SPAC trades as a unit that combines the common stock and the warrants. After 54 days, the SPAC may be split into three different publicly traded parts: the common stock, the warrants, and the full unit. Holders of both the units and the common stock are asked to vote to approve the proposed business combination with the private company. Whether investors vote to approve or deny the merger, they have the option to redeem their shares for the per-share value of cash in the escrow account. Those holding units may redeem their common shares for cash while being allowed to keep the warrants. This redemption process can create an almost risk-free trade, where they purchased the IPO shares for $10 and redeemed the common shares for up to $10 in cash while being able to sell the warrants or retain them for the upside in the publicly traded company for up to five years.

Klausner and Ohlrogge explain how the process dilutes the investors holding the common stock of the SPAC. Because there is a significant community of arbitrageurs who routinely redeem their common shares for cash, the average SPAC has only $6.67 in cash at the time it merges with the target. In order to consummate a merger with over 80% of the value of the IPO, additional fundraising is required by as many as 75% of SPACs. The sponsor of the SPAC often turns to the private investment in public equity (PIPE) market in order to raise the funds needed to replace the cash paid out to redeeming shareholders. If the PIPE is raised at a discount to the price of the publicly traded shares, the common shareholders experience additional dilution. If the SPAC is unable to raise additional funds in the PIPE market, there may be insufficient cash to complete the combination with the public company.

After the private company has been named, the process begins of transitioning the public listing of the SPAC into a public listing of the previously private company. Once the private company agrees to the business combination, a shareholder vote is required to approve the deal. After shareholder approval, a de-SPAC transaction takes place, where the escrowed cash and additional funds raised are provided to the private company, and the private company assumes the public listing of the SPAC. Note that after the de-SPAC transaction is completed, the company is publicly traded and the SPAC no longer exists. The publicly traded shell company of the SPAC has been converted to the publicly traded shares of the operating company. The SPAC units are converted into common stock and warrants and the units cease to exist. Both the common stock and warrants will continue to trade until the warrants have expired or been exercised.

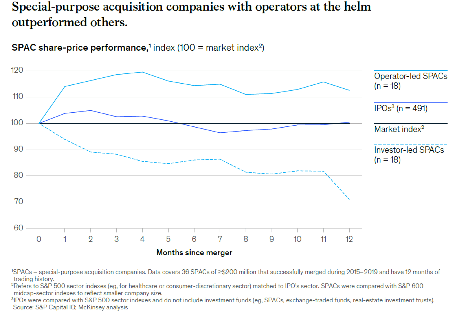

Investors and private companies targeted as business combinations should carefully consider the potential conflicts of interests and total costs of the SPAC structure. There are several key concerns regarding the dilution of the long-term shareholders and the performance of the publicly traded shares of the operating company. First, in compensation for their services and the funding of initial expenses, the sponsor of the SPAC earns up to 20% of the shares of the operating company, known as “promote.” Second, the ability for investors to redeem their shares for cash while keeping the warrants gives an economic return to investors who had little capital at risk and ultimately did not contribute capital to the business combination. Finally, the dilution from warrants and redeeming shareholders results in the majority of SPACs underperforming the public market and traditional IPOs during the first year of trading. This underperformance is concentrated in SPACs led by sponsors who come from the investing community, while SPACs led by operators, such as CEOs who have led companies in the industry of the target company, have historically outperformed the market.

Source: “Earning the Premium: A Recipe for long-term SPAC Success.” Kurt Chauviere and Tao Tan, McKinsey and Co, September 2020. How can

SPACs be structured to provide greater value to private companies’ long-term shareholders? When evaluating a SPAC, investors and private companies need to consider the dilution features of the structure. As previously shown, due diligence regarding the experience of the sponsor should be conducted, as operator-led SPACs tend to outperform SPACs led by financiers. The track record of the sponsor should be evaluated to see how many prior companies the sponsor has purchased or taken public, including the after-market performance of those companies. The structure of the sponsor promote is also important, as sponsors taking less than 20% promote or the sponsor and PIPE investors agreeing to lock-up periods of one year or longer may contribute to lower dilution and higher aftermarket returns. The redemption structure also impacts the dilution, as allowing cash to be withdrawn from the SPAC before the business combination is completed increases dilution by requiring new financing, often at terms more favorable than those for existing shareholders. Finally, the warrant ratio matters, as units including one warrant cause much more dilution than units including between 0.25 and 0.5 warrants per share. SPACs issued in 2020 were more likely to include 0.5 warrants or less, while warrant structures were more lucrative in the past.

Perhaps the most investor-friendly SPAC recently issued is the Pershing Square Tontine Holdings. These units include warrants on one-ninth of a share that can be kept by redeeming shareholders and additional warrants on two-ninths of a share that can only be kept by shareholders maintaining the stock position until after the business combination has been completed. This structure also has very low promote, where Pershing Square can only exercise the 6.21% stake held through purchased warrants after shareholders have earned a 20% return. “Tontines” are annuities that pay a regular income to all surviving investors, while the share of investors who have died are given to the surviving investors. The Pershing Square SPAC has tontine-like features, where the warrants forfeited by redeeming shareholders are reallocated to shareholders who continue to hold the SPAC beyond the time of the completion of the de-SPAC transaction.