By Phil Huber, CFA, CFP®, Chief Investment Officer at Savant Wealth Management.

Watch a recent conversation between Phil Huber, CFA, CFP® and Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CIPM, FDP as they discuss Phil’s new book, The Allocator’s Edge, and how financial advisors might best approach building portfolios in a challenging environment.

If there was ever an environment ripe for the reimagination of traditional portfolio construction, this is it.

Expensive equity markets entering a downtrend? Check.

Historically low but rising interest rates? Check.

The highest inflation in four decades that looks less “transitory” by the day? Check.

With these three puzzle pieces in place against a backdrop of geopolitical conflict, financial advisors are as incentivized as ever to think outside the box and embrace alternative investments as a source of additional portfolio diversification. Clients are accustomed to seeing the occasional red in the stock portion of their asset allocation – it comes with the territory of being an equity investor. What they’re not as used to seeing is their bond allocation down right alongside stocks like we’re seeing year-to-date.

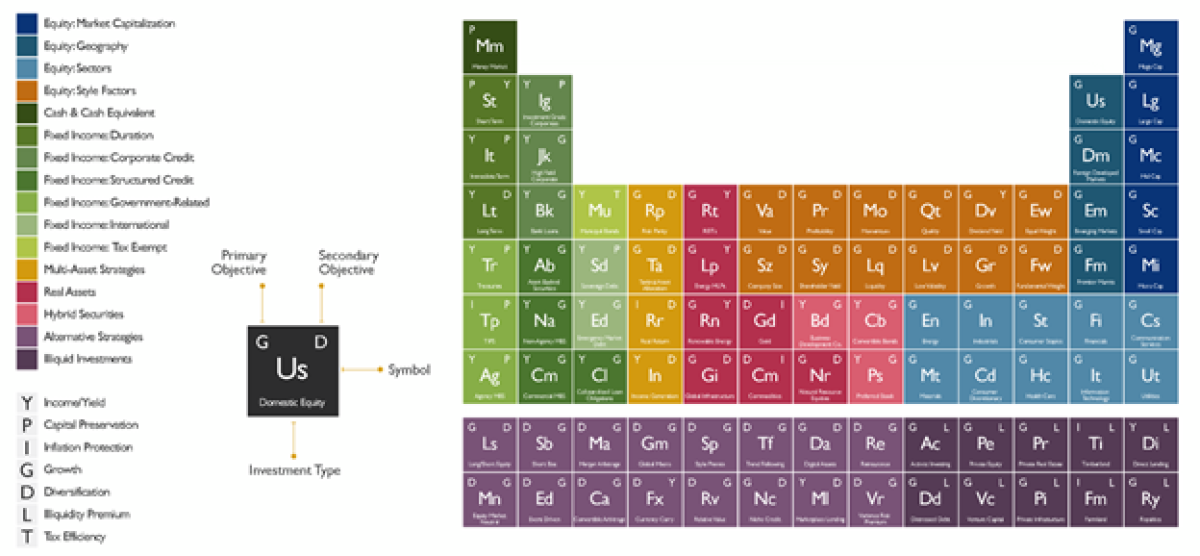

Concurrently, the opportunity set for accessing valuable and diversifying non-traditional risk premiums is as great as it’s ever been for financial advisors serving high-net-worth clients. The investable universe has expanded, and the “elements” we have at our disposal to build portfolios with has grown by leaps and bounds.

Yet many allocators within the wealth management industry still stubbornly cling to the familiarity and comfort of the canonical 60/40 stock-bond mix.

The 60/40 Security Blanket

It’s easy to understand why advisors haven’t been rushing in droves to fix what they don’t perceive to be broken. After all, the 60/40 has historically had a lot going for it:

- It’s done quite well in absolute and risk-adjusted terms across multiple market cycles.

- It’s incredibly easy to implement with a couple ticker symbols and a few clicks of a mouse.

- And perhaps most importantly, it’s intuitive to the average investor.

Meaningful shifts in portfolio construction are challenging not because we lack the tools and methods, but due to the simple fact that it is hard to stray from convention and act independently. Few argue the math confronting traditional portfolios, but fewer act differently because the 60/40 is the collective security blanket we have all clung to.

In 1997, Apple made a splash with their “Think Different” ad campaign, which was widely assumed to be a response to IBM’s slogan “Think.” Quite ironic, in that the same way “no one ever got fired for buying IBM,” allocators rarely get fired for recommending a 60/40.

For those familiar with power laws, the 80/20 rule applies to alternative investments. If they account for 20% of the portfolio, they’ll be the source of 80% of client questions. While that may sound daunting, responding to these inquiries is not as challenging at it may seem and much of it can be nipped in the bud on the front end through honest, straightforward, and regular communication.

George Bernard Shaw said, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” Often what we deem to be effective communication and education is interpreted by our clients as finance-speak and technical jargon. To bypass this, I have compiled a series of best practices, tactics, and anecdotes to use when translating the benefits of alternative investments in a portfolio in ways that clients can understand.

Set Reasonable Expectations

It’s crucial to set reasonable expectations before your clients set unreasonable ones.

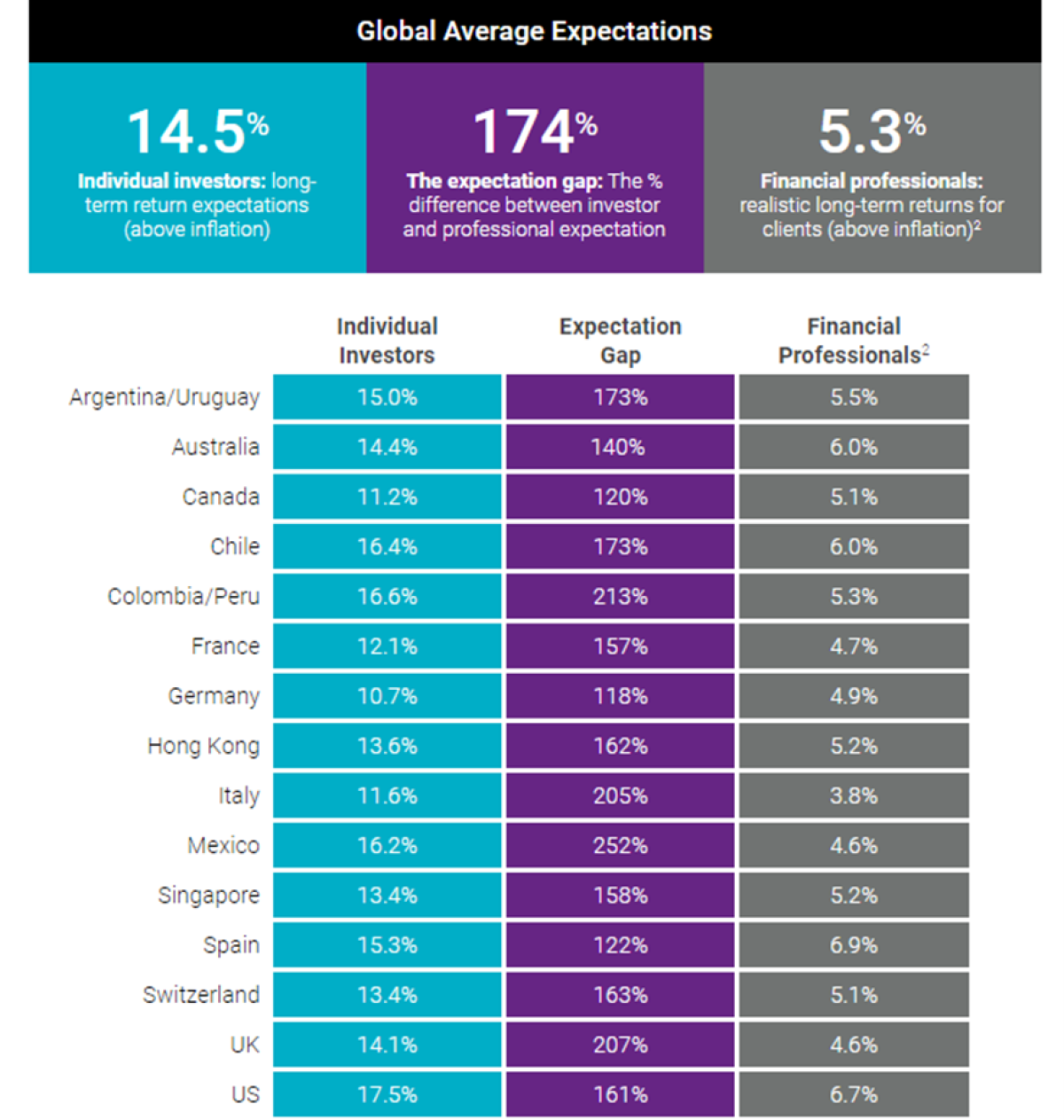

A 2021 survey by Natixis of 8,550 investors globally highlights just how overly optimistic, and perhaps unrealistic, our expectations can be. The financial advisors surveyed had fairly conservative return expectations of roughly 5% above inflation for a diversified portfolio. The individual investors surveyed, on the other hand, had average expectations of 14.5% above inflation. The expectation gap between professionals and individuals varied by country but was consistently positive across the globe.

Source: Natixis, “2021 Global Survey of Individual Investors”

It’s hard enough developing return expectations for traditional portfolios, let alone for asset classes and strategies that investors have yet to experience first-hand or that have limited historical data sets to analyze. When expectations are lofty, and our subsequent experiences run counter to those desires, bad outcomes are likely to follow. This predicament is just one reason why alternatives have been an acquired taste for most investors.

Be honest and transparent when reviewing the trade-offs between conventional and unconventional approaches. Don’t sugar-coat the challenges facing fixed income and don’t overpromise the benefits of alternatives.

“Embrace the suck” is a term used by the military that refers to dealing with bad situations. With more moving parts in a more diversified portfolio, it’s best to create an understanding with the end client that every time you meet—whether that be quarterly, semi-annually, or annually—that there will always be something in the portfolio that “sucks.”

Unconventional portfolios are going to be uncomfortable to hold at times. They will look and behave different than those of our peers. As Howard Marks notes, “Non-consensus ideas have to be lonely. By definition, non-consensus ideas that are popular, widely held or intuitively obvious are an oxymoron. Thus, such ideas are uncomfortable; non-conformists don’t enjoy the warmth that comes with being at the center of the herd.”

The Double-Edged Sword of Diversification

These are my three favorite quotes about diversification:

“Diversification means always having to say you’re sorry.”

— Brian Portnoy

“Diversification is a regret-maximizing strategy.”

– Jason Hsu

“The bottom line is that since diversification is the only free lunch in investing, you might as well eat a lot of it.”

— Larry Swedroe

To recap: the only free lunch in investing means always saying you’re sorry and being full of regret. Doesn’t sound like much of a free lunch, does it?

Such is the frustrating nature of diversification.

Don’t get me wrong—I absolutely believe in the power of diversification. But diversification can take a long time to bear fruit, as you tend to oscillate between periods of relative and absolute disappointment. We’re always going to wish we had more of one thing and less of something else.

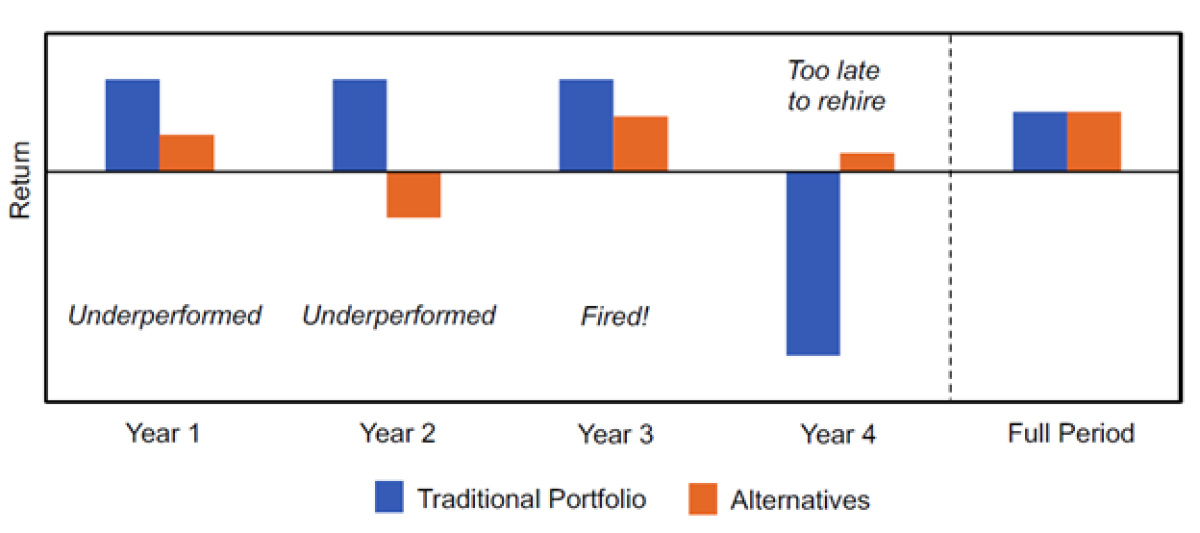

The hypothetical illustration below from Newfound Research highlights that the experience of owning alternatives is not always easy, despite the meaningful diversification benefits they can provide over time. It also shows how patience can be a virtue and that as investors, we often have trouble seeing the forest for the trees.

Source: Newfound Research. This is intended for illustrative purposes only. The example provided is hypothetical and not representative of actual data.

In some markets, we regret every dollar we put into diversifiers and in others we regret every dollar we didn’t put into diversifiers. The 1990s and the 2010s were both challenging decades for diversification. Perhaps not surprisingly, they both coincided with enormous bull markets in U.S. stocks that were accompanied by rising valuations and declining yields.

Every financial advisor, at some point in their career, has been on the receiving end of a complaint from an unhappy client seeking to abandon diversification (usually right before it is needed most). Much like a global portfolio of stocks and bonds often feels like it is losing relative to an inappropriate benchmark like the S&P 500, a diversified portfolio including a material allocation to alternatives will at times feel foolish versus just owning a 60/40. That doesn’t mean it won’t be proven the right decision in the end.

Setting the Record Straight: Diversifiers vs. Hedges

One of the most common pitfalls encountered when allocating to diversifying strategies is the confusion between non-correlation and negative correlation. For an uncorrelated investment, the stock market doing X over a particular day, week or month should not intuit any degree of confidence in what the diversifying strategy is likely to have done. But that doesn’t stop us from trying anyway!

If the underlying return stream is truly unrelated to the market, then the market falling means your return could be positive, negative, or flat. As much as we would all love something that went up every time stocks took a dive, those types of investments often come at a cost, and that cost is negative expected returns.

Most allocators intuitively like the idea of uncorrelated returns, but most balk at the actual experience of owning uncorrelated return streams. It’s important to keep in mind that “uncorrelated” means the results shouldn’t bear any relation to what’s happening in broader markets.

Make the Unfamiliar Familiar

A phenomenon known as the Lindy Effect states that anything non-perishable has a future life expectancy proportional its current age. In other words, the longer something exists the more likely it is to continue to exist.

Agriculture, insurance, credit—these asset classes have existed for millennia. In the case of credit, its earliest and most primitive documentation can be traced to ancient Egypt, with letters of credit on clay tablets dating back as far as 3000 B.C. Credit even has historical roots at the philosophical level, as the Athenians widely believed that life itself was a loan from the gods.

Academic research has also documented the existence—and persistence—of investment styles and risk premia such as value, momentum and trend following dating back well over a century. As Robeco’s David Blitz notes, “Risks that command a premium should continue to be rewarded with a premium, and mispricing resulting from investor behavior should be persistent as well, since our behavioral tendencies are pretty much hardwired in our DNA.”[1]

Allocators should make it their mission to make alternative investments feel less… alternative. Many alternative assets are merely old wine in new bottles. It is only now that they are being unlocked for mainstream adoption. Find ways to incorporate the long histories of these asset classes when introducing them to your clients.

Prepare for Long Winters

Time dilation is all too real in the realm of investing—especially when things aren’t going your way. Days can feel like weeks, weeks can feel like months, and months can feel like years. In the context of an investor’s lifecycle, five to ten years is not that material. Good luck telling that to the investor.

Most investors have a much longer horizon than they give credit to. Even a newly minted retiree has another 20-odd years of life expectancy ahead of them to plan for. Human nature leads us to think of the long term not as point A to point Z, but to each letter of the alphabet along the way. This poses tremendous challenges to our ability to recognize these long horizons as a benefit in our decision-making. Investment portfolios are generally designed to support the spending needs of our future selves decades from now, but you wouldn’t know it in how our behavior manifests.

Alternatives get a much shorter leash for underperformance than traditional investments owing to their novelty and unfamiliarity. We must remember that bad things happen to good processes. More often than not, when something seems broken it is usually just bent. Investors should foster a similar long-term view for non-traditional investments as they would for stocks—the seeds need time to grow.

That doesn’t mean you should never consider that something has permanently changed. There is a difference between being disciplined and patient versus being rigid and stubborn. Always keep an open mind, just not so open your brain falls out.

As cliché and trite as it seems to say, giving any investment with a positive expected return a long enough runway to succeed is paramount to success. As I type this, I can almost hear you saying, “easier said than done.” Asset managers, financial advisors, institutional allocators—we are all under immense pressure to deliver short-term results. Even the most long-term oriented among us will recognize that the long term is merely a chain of interconnected short terms, each of which must be lived through by somebody. As allocators, the key thing is making sure we are doing our damnedest to put our constituents in a position to win, and to do whatever is within our power to ensure that journey is as smooth and free of turbulence as possible through our communication, education and responsible setting of expectations.

Jobs to be Done

“Jobs to be Done” is a theory popularized by Clayton Christensen, famous for his work on disruptive innovation. At its core, it recognizes that our lives are full of jobs to be done and we “hire” products to accomplish them. If they do a good job, we’re more likely to keep them for the next time. If they fail, odds are they will be “fired.”

Portfolios have a variety of potential jobs to be done. The magnitude of those jobs is dependent on the end user. Stocks can perform some jobs well, while failing at others. Same goes for bonds. The ability of investments to succeed at doing a job—whether that be generating income, offering diversification, or protecting against inflation—varies over time. Alternatives are merely another avenue to do another job within a portfolio that cannot be sufficiently accomplished by stocks or bonds.

Football provides a useful analogy here. Offense, defense, and special teams all have specific jobs to be done. And within each of those units, individual players have even more specific jobs. If we think of stocks as our offense, bonds as our defense, then perhaps alternatives are our special teams—picking up slack when the other units are lagging.

Sticking with sports analogies, you could look at the stat sheet of last night’s basketball game and assume a player had a bad game because they didn’t score any points. But what if that same player had eight rebounds, three steals, and five assists? That player contributed to multiple jobs, even if they didn’t rack up any buckets.

Incremental Upgrades

As fiduciaries and professionals, we should always be seeking ways to upgrade the experience and outcomes for our clients. This goes for guidance around financial planning topics such as estate planning, tax planning and retirement planning. It also relates to the client service we provide and the various components of our technology stacks that touch the client in some way. Clients should similarly understand that we are always looking for incremental improvements in the way we design and implement their portfolios.

Few iPhone owners noticed any material difference between their iPhone 6 and iPhone 7. But you can best be sure they would be able to see the stark contrast between the first-generation iPhone and the latest. The original iteration of the iPhone and the recently unveiled iPhone 13 both achieve the same core functionality—talk, text, download apps, take pictures, surf the web. Yet if given the chance, exactly zero people would select the original if given a choice between the two. The reasoning is straightforward—today’s version has additional features and capabilities AND does all the core stuff better, faster, and more efficiently. The incremental upgrades seem negligible along the way but can be quite substantial when stacked on top of one another.

***

Great investments (and by extension great portfolios) are nothing if not paired with equally great investors. The best-laid investment plans can fall apart because of bad investor behavior, poor communication, or mismatches in expectations.

The success of a portfolio is contingent upon the comfort of the investor holding it. The clients most likely to maintain and stick with a portfolio during challenging times are the ones who understand the process behind it the best. This underscores the importance of effective communication, education and transparency between allocator and client.

[1] D. Blitz, “Why I am more bullish than ever on quant,” Robeco (November 2020).

About the Author:

Phil Huber has been involved in the financial services industry since 2007. He worked for Huber Financial Advisors from 2008 until it joined with Savant in 2020. Prior to joining Huber, he was employed at a global asset management company where he worked closely with financial advisors to develop investment strategies for their clients.

Phil earned a bachelor’s degree in finance from the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. He is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional, has attained his Chartered Financial Analyst® (CFA®) designation, and is a member of the CFA Society of Chicago.

Phil has been featured in a number of notable media outlets, including The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, InvestmentNews, CityWire RIA Magazine, and Bloomberg TV. He produces his own investing blog, bps and pieces, and recently authored his first book, The Allocator’s Edge: A Modern Guide to Alternative Investments and the Future of Diversification.

Phil and his wife Christie live in the northwest suburbs of Chicago where they enjoy reading, yoga, and spending time with their daughter Hannah. He is also a lifelong, diehard professional wrestling fan.