By Andreas Rothacher, CFA, CAIA Head of Investment Research, Complementa AG

& Janick Rensch, Head of the Infrastructure Competence Center, Complementa AG

Infrastructure Allocations & Backdrop

For over a decade until 2022, institutional investors were faced with low interest rates on their fixed income securities[1]. This environment made it increasingly difficult to achieve target returns without breaching risk budgets (expected volatility). In the search for yield, many investors turned to alternative investments as potential bond substitutes. In this context, infrastructure investments have become more mainstream, and an increasing number of institutional investors, such as pension funds, have added infrastructure assets to their strategic asset allocation[2]. Despite bond yields increasing in 2022 and remaining at elevated levels in 2023 and 2024, infrastructure allocations are now firmly anchored in the asset allocation policies of many institutional investors.

In this article, we will elaborate on some key features of this asset class and what investors should consider when investing. We will also share some observations about Swiss and German institutional investors and their infrastructure allocations.

Infrastructure Asset Class & Funding Gap

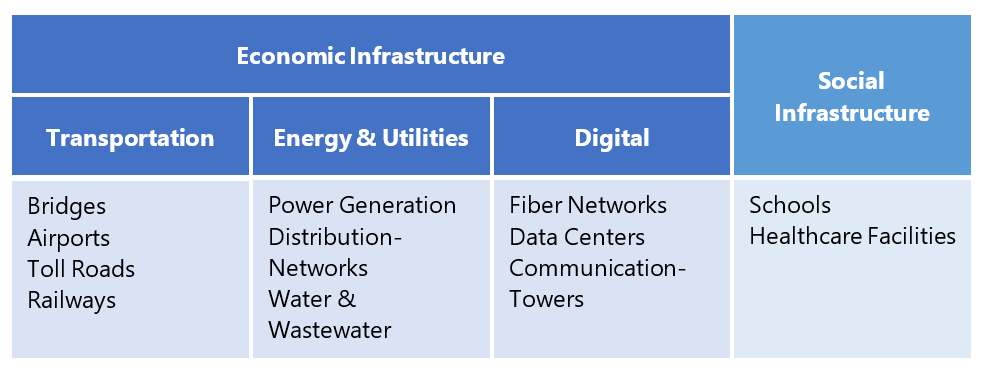

Infrastructure is defined as the basic physical structures and facilities of a region or country that are essential for its functioning. This often involves the production or production process of public goods. Infrastructure investments are vital to the development and growth prospects of an economy. Examples of infrastructure assets include communication networks, roads, and sewage and water systems (for more examples, see the table below). In general, infrastructure assets can be divided into economic infrastructure (enabling business activities) and social infrastructure (supporting the quality of life).

Overview of Infrastructure Sectors (Non-exhaustive)

Infrastructure projects tend to be capital-intensive and can be funded publicly, privately, or via a combination of both (public-private partnerships). Besides building new infrastructure assets like telecommunication towers, this also includes the maintenance of existing assets, such as roads and railways. Additional needs for investment can arise from the transition to a more sustainable economy. This includes investments in renewable energy production (e.g. solar, wind) and other assets (e.g. energy storage and electrical grids). As investment needs increase, the funding required to realise these projects becomes significant. The global infrastructure funding gap is estimated to reach $15 trillion by 2040[3]. Given the existing high government deficits and rising public debt levels, private capital will be needed to bridge this funding gap.

This offers a wide variety of investment opportunities for investors. It also indicates that infrastructure as an asset class is highly diverse, allowing investors to avoid overcrowded markets while identifying assets that align with their risk-return profile. The high funding needs in various sectors offer ample opportunities for sector and country diversification, but investors must be selective when implementing their infrastructure allocation.

Historical Adoption of Private Infrastructure

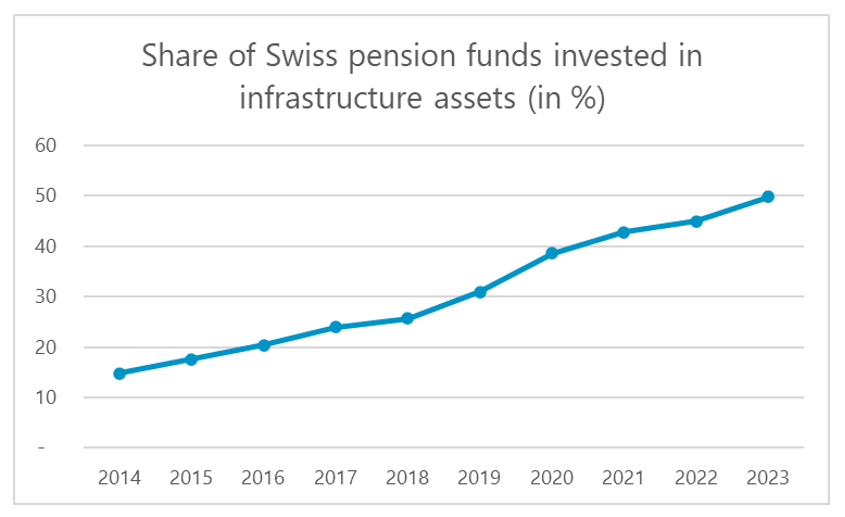

Australian and Canadian pension funds were among the early adopters of private infrastructure as an asset class. Making use of their long-term investment horizon, the first investments were made in the 1990s. Other investors in the US and Europe followed. Over the last few years, allocations have increased. This can also be seen in the context of decreasing fixed income allocations during the long period of low interest rates in the 2010s. For example, among Swiss pension funds, the capital-weighted average fixed income allocation decreased from 39.5% in 2014 to 31.6% in 2023. On the other hand, quotas in real estate and alternatives (especially infrastructure) increased significantly. A key driver of this development was the substitution of bonds with other return sources. At the end of 2023, capital-weighted average infrastructure investments represented 2.5% of the overall asset mix of Swiss pension funds, making them one of the largest alternative subcategories. Besides the quotas, the number of pension funds invested in the asset class has also increased significantly. Over the last decade, the proportion of Swiss pension funds invested in this asset class has grown significantly, from around 15% to approximately 50%. Since 2021, more Swiss pension funds have invested in infrastructure assets than in any other subcategory of alternatives. Infrastructure has thus emerged as the most popular alternative investment subcategory. The regulatory environment may also have contributed to high adoption rates among Swiss pension funds[4].

Source: Complementa Pension Funds Study 2024

Similar allocation trends can also be observed among German institutional investors, although at lower levels. Depending on the type of investor, set-up, and investment vehicles, regulation in Germany can be less favourable and flexible compared to Switzerland. Nevertheless, we see many of our German clients discussing the asset class and/or allocating new investments.

We would also like to highlight that adoption rates can fluctuate between infrastructure debt and equity investments. For pension funds, we tend to see a clear preference for equity investments, while infrastructure debt seems to be more popular with insurance companies. Regulation is of course an important driver of this preference. There are also some institutional investors that invest in both infrastructure debt and equity. The allocation decision depends on the current yield levels of infrastructure debt and the relative return premium of equity investments over debt.

Portfolio Implementation: Building Resilient Portfolios

Before investing in an asset class for the first time, it might be beneficial to spend some time educating the investment committee or board members. This should help to establish a common understanding and raise awareness of the potential return and risks associated with the infrastructure asset class. In addition to continuous education, it may be beneficial to hire external specialists, such as investment consultants, to complement existing expertise. After all, mistakes made in the selection process in private market assets can be costly or even irreversible.

The starting point of any allocation is the asset-liability management study. Investors should be clear about their motivation for including infrastructure assets in their portfolios. Are these investments undertaken to enhance portfolio returns, increase diversification, or provide inflation protection? A clear understanding of the motivation will help investors to choose an appropriate risk-return profile. This, in turn, gives an indication of the proportion of core, core-plus, value-add, and opportunistic assets suitable for the investor. Core and core-plus assets have higher cash flow returns, while capital gains might be lower compared to value-add investments. Opportunistic assets typically include development projects that generate little to no cash flows, with returns primarily driven by capital appreciation. A strong shift in this direction could mean that the infrastructure allocation starts to behave more like private equity and less like traditional infrastructure assets. In an asset allocation context, this could be undesirable if an investor already has a separate private equity allocation.

In addition to the risk profile, investors can strategically plan their asset allocation within the infrastructure asset class. Defining this allocation involves determining sector weights, regional/geographical allocations, and corresponding bandwidths. Larger investors (e.g. those with significant total AuM and/or infrastructure AuM) can be more granular in their allocation within the asset class.

As infrastructure investments require a long investment horizon and are illiquid by nature, investors should have a clear understanding of their own cash flow needs and the liquidity profile of other portfolio assets. The existence of other illiquid assets in the portfolio (e.g. private equity, unlisted real estate, private debt) will limit the proportion of additional portfolio assets that can be invested in unlisted infrastructure assets. In the context of an ALM study, this means that the process must account for the exposure to illiquid assets, in addition to risk-return optimisation.

Identifying the Right Partners: Selection & Portfolio Construction

Successful investment in infrastructure assets largely depends on selecting the right managers. The selection process should be rigorous, requiring detailed due diligence on strategy, execution capabilities, and deal pipelines. The evaluation should include both factors that are qualitative (e.g. team) and factors that are quantitative (e.g. performance track record). For multi-manager portfolios, investors should focus on portfolio construction by selecting managers whose strengths complement each other, such as different sector allocations or geographic focuses, to ensure a well-rounded and diversified investment approach.

In addition to finding the right partners, investors should also define whether they want to invest in closed-end structures, evergreen structures, or a mix of the two. Closed-end structures have a defined investment period and a fixed lifespan, requiring investors to manage capital calls and distributions within a set timeframe. If the investor chooses to focus exclusively on such funds, they must set up a process to continuously replace maturing vehicles and to select new managers if needed. If a mix of both structures is applied, the evergreen vehicles can serve as a baseline allocation, and this can be complemented with closed-end vehicles. For smaller and mid-size investors, evergreen structures (not to be confused with semi-liquid structures for the private wealth channel) can provide a simplified approach to the administration of such investments and the associated capital calls and distributions.

Risk Management

Once an initial investment has been made, continuous monitoring of the existing portfolio and managers is advisable. One challenge investors face is the lag in valuations and the difficulty in finding appropriate benchmarks. Risk management must therefore include more qualitative metrics, such as portfolio characteristics (e.g. concentration risk, loan-to-value ratios of portfolio companies). Regulatory changes and operational risks of underlying assets must also be understood and monitored. Some of these risks can be mitigated by working with experienced managers and ensuring portfolio diversification across sectors and regions.

Investors should also be aware of the illiquidity of unlisted investments. This will be especially important if institutional investors are faced with negative net cash flows and/or when allocations to other illiquid assets, such as unlisted real estate or private equity, are high. These risks can be addressed with periodic liquidity planning and careful consideration of asset class weights during the asset allocation process.

Periodic monitoring by an external investment controller can provide an additional layer of risk management. External experts can act as sparring partners, providing insight and guidance when evaluating more qualitative dimensions of risk.

Conclusion

Given the huge investment needs in sustainable energy infrastructure and the urgent need to renew traditional infrastructure assets, investment opportunities in the infrastructure space are likely to be plentiful. Considering this vast opportunity set and the long-term investment horizon of the asset class, investors should be structured and selective in their approach.

Infrastructure assets can provide stable, inflation-linked returns and contribute to addressing global challenges like climate change, urbanization, and digital transformation. Investors should not underestimate the vastness and complexity of the asset class, nor the diversity of implementation approaches. Ongoing education as well as continuous portfolio monitoring are, therefore, key aspects of successful investment in infrastructure assets.

About the Contributors

Andreas Rothacher is the Head of Investment Research at Complementa AG. In his current role, he advises institutional clients on strategic asset allocation and manager selection. In addition, he is a co-author of Complementa’s annual Swiss pension fund study (Risk Check-up). He is also the author of various articles and publications. Andreas is a Chapter Executive of the CAIA Zurich Chapter and a member of the CFA Swiss Pensions Conference Committee.

Janick Rensch is an Investment Consultant and the Head of the Infrastructure Competence Center at Complementa AG. In this role, he provides investment advice to institutional clients on their infrastructure allocations and manager selection processes. He also advises several pension funds and provides expert guidance to their investment committees. In addition, he monitors infrastructure funds, assessing key aspects such as performance, risk, and compliance to ensure alignment with client objectives.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/

[1] For Swiss franc investors the environment (2015 to 2022) was particularly challenging as Swiss franc government bond yields fell into negative territory. Other examples include Denmark which introduced negative rates in 2012 for a decade.

[2] Other fixed income substitutes include core real estate investments (unlisted) and private debt.

[3] Global Infrastructure Outlook – Investment current trends (USD 79 Trillion) vs. investment needs (USD 94 Trillion)

[4] Swiss pension funds are regulated according to the guidelines and limits stipulated by the Ordinance on Occupational Retirement, Survivors' and Disability Pension Plans (BVV 2). Alternative assets have a stipulated limit of 15%. Since 2020, infrastructure has its own stipulated limit of 10%, separate from other alternative asset classes. Pension funds can exceed the stipulated limits but must justify their decisions to the supervisory authority (Occupational Pension Supervisory Commission).