By Hilary Wiek, CFA, CAIA, Senior Strategist, PitchBook

& Anikka Villegas, Senior Fund Strategies & Sustainable Investing Analyst, PitchBook

Introduction

In PitchBook’s 2024 Sustainable Investment Survey, hundreds of respondents were asked about their sustainable investment practices across a wide variety of subject areas. For those who indicated that they do have an ESG or impact investing program, we wanted to probe some perceptions, particularly around the supposed decline of ESG and the idea that impact investing is an exercise where participants always accept that returns will be subpar, or concessionary. Reality did not reflect perception among our respondents, which we explore here.

Is impact investing necessarily concessionary?

In many conversations we have had with impact investors, they have expressed frustration with an industry perception that seeking impactful outcomes means market-rate returns are off the table. In fact, among those who have some exposure to impact investing in their investment program, most audiences selected “Perceptions or concerns about impact investing equating to concessionary returns” as one of the top three challenges that impact investing faces. This year, we wanted to see how practices compare with perception and what motivations are driving practitioners’ impact investing programs.

One key question we had for our impact practitioners concerned their priorities around market-rate returns versus impact outcomes. More than half said market- rate returns are the priority—and this was true across most respondent types. One exception was that only 34% of respondents from our “other” bucket—which included a wide array of individual companies, consulting firms, law firms, and more—made this selection. In addition, only 43% of our European respondents selected this response option, with 51% saying they use a blend of impact outcomes and return profiles to make their impact investments.

Across the board, very few respondents chose “We accept concessionary returns.” Only the “other” and investment consultant groups had more than 10% of respondents share that they accept concessionary returns—and their selection rate was only 13% and 12%, respectively. None of our VCs accept concessionary returns as a valid option for their strategy.

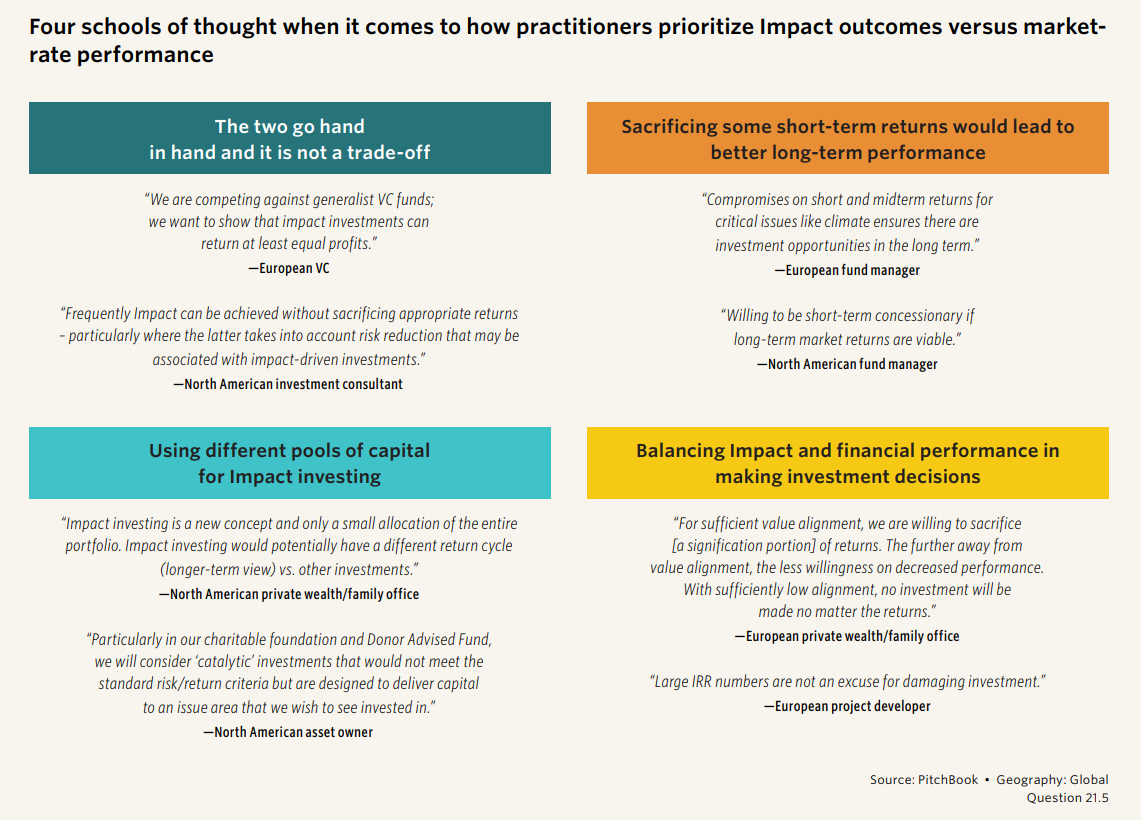

Many impact investors find themselves balancing their priorities between impact outcomes and market-rate returns. In our follow-up to this question, we asked respondents to expand on their choice. Of those who consider both, the responses fell into four schools of thought, shown in the graphic below.

As we have seen in so many aspects of sustainable investing, there is a lot of complexity to the subject, leaving room for a wide variety of implementation methodologies when it comes to impact investing. Part of the reason it can be so frustrating that sustainable investing has been politicized is that a blanket statement such as “[ESG/impact] is bad” completely misses the point that sustainable investing is not just one thing. While concessionary returns do play a part in some investors’ impact portfolios, more than half of our impact practitioner respondents would heartily disagree that impact strategies equate to abandoning market-rate returns.

Views on ESG measurement

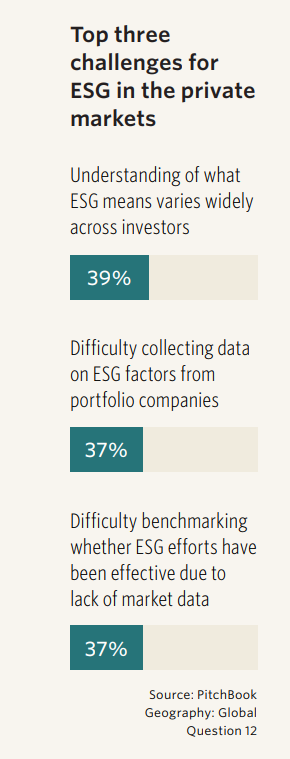

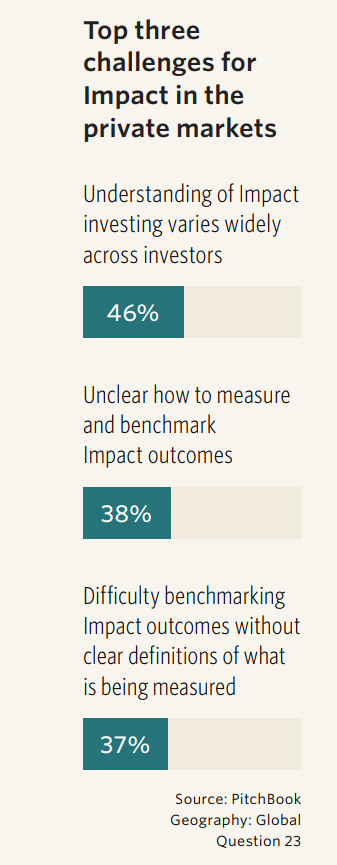

Year in and year out, the top challenges our respondents face in ESG and impact investing relate to data, measurement, and benchmarking, and this year was no exception. For ESG, two of the most selected challenges this year were data related.

Why is this such a perennial problem? Both ESG and impact investors are challenged by definitional discrepancies, as seen in the top challenge selected for each. Practitioners and especially nonpractitioners have widely varying ideas of these concepts, causing confusion around what should be measured, how to measure it, how to benchmark what has been measured, and whether measurement is important at all.

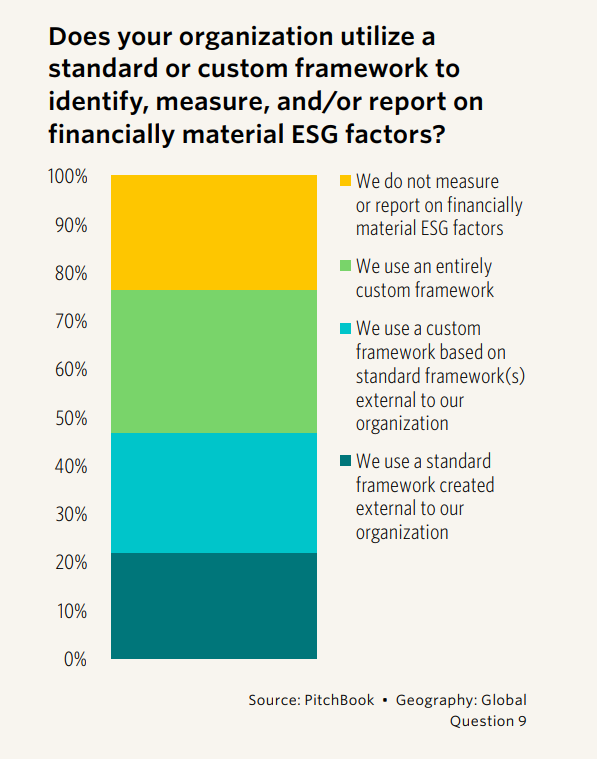

As we have reported in prior years, measuring and reporting on ESG continues to be done in a wide variety of ways. Roughly 70 different standards or frameworks were mentioned when respondents were asked how they identify, measure, and/or report on financially material ESG factors. As in our past surveys, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) were mentioned with the greatest frequency. Most of the other responses, many of which will be obscure organizations or metrics even to full-time practitioners of ESG, were named only once. As long as investors continue to have their own views on what is important from an ESG perspective, which seems to be a permanent situation, practitioners will continue to be challenged in determining the effectiveness of ESG efforts, which is something that non-ESG practitioners will frequently call out as a fundamental weakness of ESG.

When we reviewed how people described their custom methods of ESG measurement, the responses ran the gamut from “basic due diligence” to deeply technology-dependent methods, including “AI-driven data collection, filtering and proprietary algos to calculate ESG’s financial impacts on such areas as cost of equity and revenues.” Others have custom frameworks that are very specific to their own needs. “We filter for positive impact on climate environmental and filter negative against social impact,” said one respondent. One North American investment consultant indicated that while his firm does incorporate ESG into their investment analysis, they are still skeptical about the need for ESG measurement: “We have a faux policy to appease politicians. Other than that, we feel ESG is a scam.”

Several did not name any specific standard they adhere to, saying it was company and manager specific, highlighting the issue that LPs have in ESG measurement—they are getting different metrics from each of the managers they partner with, making it difficult to aggregate or evaluate ESG performance. Indeed, LPs and private wealth investors who self-identified as ESG practitioners were least likely to measure or report on financially material ESG factors at all, at 37% and 39%, respectively. From the reverse perspective, one fund manager reported that “All of our LPs have completely random frameworks which create an administrative nightmare. We are forced to pass through this administrative burden to our portfolio companies via long questionnaires.” The lack of convergence in ESG definitions and reporting is causing frustration throughout the industry.

But there is hope. Almost two years ago, we became aware of a nascent effort being made by some industry participants who agreed that 1) we cannot wait until the perfect ESG framework is designed, as it may never happen; 2) having everyone come up with their own company-specific data points means that nothing is aggregable; and 3) having data points that sound the same but are defined differently make them incomparable. The ESG Data Convergence Initiative, also known as EDCI, brought LPs and GPs together to define a very small number of measurable environmental, social, and governance metrics that the GPs could agree to measure in a common way. This group then set up a reporting mechanism so that a third party could collect the data and provide anonymized benchmarks. Based on our survey responses, awareness of this initiative is still low. We encourage those who think this sounds like a good idea to explore being a participant, as it may help the industry to take a step forward when it comes to ESG measurement and benchmarking.

Views on impact measurement

Impact investors face similar challenges in terms of what to measure, how to measure, how to benchmark, and how to define impact investing. Only 25% of our impact practitioners use a standard created outside of their organization, including those who are using that external standard in a customized way. A full 42% do not measure impact at all, despite seeking both financial and social or environmental returns with at least some of their investable assets. For those who do use some external standard, 20 different organizations or frameworks were mentioned, with the most overlap being the four people who cited SASB, which is generally thought of as an ESG framework, not one for impact measurement.

There does appear to be appetite for measuring impact outcomes among some of our impact practitioners, but there were also plenty of practitioners for whom measurement is not a top priority—the responses are barbelled. When respondents were asked how important measurement is to their impact efforts on a 1 to 9 scale, 25% gave a 1 or 2 response, indicating they do not prioritize measurement, but another 25% selected 8 or 9, indicating that measurement is of utmost importance. The mean of all of the responses was 5.08, indicating that there is a very slight skew toward measurement, but in general, there is not a consensus among impact investors in terms of measurement priorities.

Conclusion

News of ESG’s death has been premature, based on the responses from the 2024 Sustainable Investment Survey. While there are still challenges around measurement and reporting, investors continue to believe that a focus on environmental, social, and governance risks make for more sustainable long-term businesses with returns that can be at least as attractive as investments without an impact or ESG focus.

About the Contributors

Hilary Wiek, CFA, CAIA is a senior strategist at PitchBook, where she leads PitchBook’s coverage of fund strategies and performance, publishing primary research on the alternatives space and contributing to core report development. Wiek also heads PitchBook’s coverage of the ESG/impact investing space. She has over 20 years of experience in asset owner, manager, and advisory roles. Prior to PitchBook, Wiek was the director of investments at the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundations. Before that, she worked in senior positions at Segal Rogerscasey, the South Carolina Retirement Systems Investment Commission, Buckingham Financial Group, Dayton Power & Light, and KeyCorp. Wiek received a master’s degree in finance and economics from Case Western Reserve University and a bachelor’s degree in leadership and finance from the University of Puget Sound.

Anikka Villegas is a senior fund strategies & sustainable investing analyst at PitchBook, where she publishes primary research on the alternatives space, contributes to core reports, and serves as an ESG and impact investing specialist. Prior to joining Pitchbook, Villegas was an ESG analyst at Bridge House Advisors, an ESG and sustainability advisory firm. Before that, she was an associate at Malk Partners, a consultancy advising private market investors on ESG risk management and value creation. Villegas received a bachelor's degree in philosophy, politics, and economics from Pomona College.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/