By Steve Novakovic, CAIA, CFA, Managing Director of Educational Programming, CAIA Association

In a previous blog post, I discussed the merits of a risk-based portfolio objective. While writing the post, I avoided taking a detour to ramble about performance analysis and benchmarking. Instead, I’ve decided to devote a series of blog posts to the subject. Welcome to Part 1! I should probably warn you that this is a hot-button issue for me (and possibly many current and former LPs), so you’ll have to indulge me in a little hyperbole and facetiousness. With that disclaimer, let’s jump in.

Return factors: A different meaning

In Innovation Unleashed: The Rise of TPA we discuss the role of the board within the governance dimension of the framework. Specifically, that the board should delegate investment responsibility to the investment team and focus on defining the portfolio objective. Notably, in delegating investment responsibility to the team, the board is not ceding authority on evaluating portfolio performance. As fiduciaries, the board must regularly evaluate the effectiveness and decision-making of the team. If the investment team is underachieving, it is wholly appropriate for the board to make changes.

The question I’d like to confront in this missive is how boards should actually evaluate the success of the investment team. Said differently, what defines a successful outcome for a Limited Partner? A simple question with a deceptively complex answer.

Presumably, the first place a board would start when analyzing performance is evaluating returns relative to the objective they set. As previously discussed, most boards define a return-based objective. Seemingly, this would make for a simple analysis. Did the investment team meet or exceed the return objective? While that may be the right question to ask, arriving at an answer is complicated by several factors (I discuss eight different factors across both parts).

Factor 1: Absolute return objectives

I touched on this topic in my previous blog post, so I’ll avoid going into the same level of detail here. In summary, absolute return objectives are particularly common in the E&F world and effectively define a fixed return threshold necessary to ensure preservation of principal. The foundation of such an objective is intuitive and defensible but may not always be realistic to achieve (good luck generating a portfolio-level 8%+ return in 2008).

As I also pointed out in the same post, equity markets have seen extended periods of low-single-digit returns. Unless the portfolio was leveraging high-risk assets, it is doubtful that the investment team generated returns close to the target.

As obvious as it would seem to hold an investment team to this absolute return standard, they can only play with the cards they were dealt. If markets are going through a tough stretch, there’s little anyone can do to build a diversified portfolio that substantially outperforms low-returning markets to reach the absolute objective.

Firing an investment team because beta markets generated returns lower than your absolute return standard would be a naïve and unfair decision, in my opinion.

Factor Two: About time (Does anybody really know what time it is? Does anybody really care?)

When evaluating the performance of an investment team, what time period should we evaluate? In theory, most LPs are long-term investors. So, in theory, should we not evaluate their performance over the long term? But what is the long term? And what if they have a really bad year (or two or three)? At what point is it fair for the board to intervene?

To use a simple analogy, an investment portfolio is like a barge in the ocean. It can move fairly well in the direction it’s initially pointed, but it may take some time to get moving in a completely different direction. A diversified portfolio with a meaningful allocation (up to 50%+) to illiquid and semi-liquid investments can take years to change in profile and exposure, if so desired (absent a significant portfolio overlay or expensive secondary transaction).

In many ways, the performance of an LP portfolio is mostly baked up to three years in advance. Barring large hedging programs or radical changes to liquid allocations, there is little an LP with material exposure to alts can do to meaningfully disrupt the exposures and factors that drive performance in any given year. Take, for example, the average LP performance in Fiscal Year 2022. This was the year of venture capital driven by the hottest IPO market since the tech bubble.

The venture capital seeds that were planted by LPs who benefitted from that performance were sown anywhere from three to seven years prior. An LP who first invested in venture capital in FY ‘22 would have seen zero benefit from that exuberant exit market. The same would be true for an LP who first invested in VC in FY ‘21 or even FY ‘20. Many private market investments are long dated and take time to come to fruition and pay dividends.

If the investment board replaced the investment team in FY ‘21 and then enjoyed exceptional performance in FY ‘22, was the new investment team responsible? Absolutely not. Similarly, had the opposite been true (i.e., FY ‘22 was a dismal year due to poor VC returns), would the board blame the new investment team for decisions made five years prior?

One other real-life example of short-term analysis challenges. In 2023 and 2024, The S&P 500 generated 20%+ returns in consecutive years for the first time since the 1990’s tech bubble. Good luck to all other investment strategies trying to keep up with that return. What’s that? You set your asset allocation three years ago and didn’t choose to allocate 100% of your assets into U.S. stocks? That clearly qualifies as an offense worthy of being fired, no?[1] Some years, a hot market works in your favor. Other years, a hot market works against you. But that’s okay, because we have our eyes on the long-term prize… right?

Let’s hope I’ve convinced you that one-year (or even two-year) performance analysis is a fool’s errand. So, long-term it is.

But what exactly qualifies as long-term? To be honest, I don’t have a good answer for you. At least three years, although one could argue that is still too short term. Probably five to seven years? One of the LPs we spoke with while researching TPA told us they prepare an efficient frontier using 50-year capital market expectation forecasts. I’d argue that may be too long of a time frame to wait to measure performance. . .

Factor 2a: But what 3- (or 4-, or 5-, or 50-) year time period should I look at?

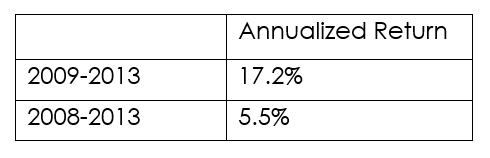

Do you want to really know what grinds my gears? When people do point-in-time benchmarking! “From 2009 to 2013, so-and-so investors were horrible and terribly underperformed the stock market.” Oh, is that so? Funny that you chose one of the greatest equity bull market periods in modern history to support that claim. How would they have looked if you’d measured from 2008? Would that have made any difference? Only 11% per year!

Point-in-time return analysis is the scourge of my existence and should be eradicated from the face of the earth (I told you this might get hyperbolic). Give me annualized rolling returns any day of the week. That’s the kind of analysis that can tell you something! Let’s be honest, it’s impossible for anyone (yes, even Warren Buffett) to outperform year-in and year-out. Instead, what we’re really looking to do is outperform more often than not. Rolling returns help us evaluate just how successful we are at that.

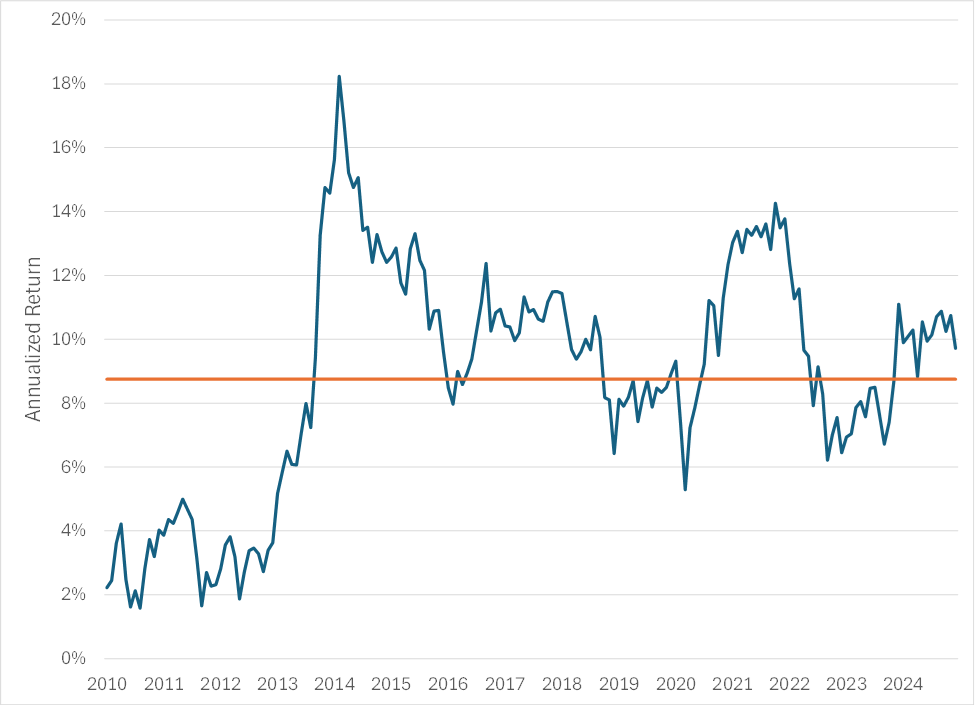

Rolling 5-year returns of 70 / 30 portfolio[2]

To illustrate my point, the chart above shows the rolling 5-year returns of the 70/30 portfolio from 2005 through 2024. Included is a hypothetical absolute return benchmark of 8.75%. For much of the last decade-plus, the 70/30 portfolio crushes the absolute return benchmark. Over the full measurement period, the 70/30 benchmark has annualized five-year returns in excess of 8.75% roughly 54% of the time. Meaning, there are plenty of instances where I can choose point-in-time dates that show the 70/30 doing worse than my hypothetical absolute return benchmark.

Like I said, not even Warren Buffett outperforms every single year, but what he does do is outperform more often than not. Rolling returns analysis helps us see how often there is outperformance and the consistency of that outperformance.

Factor 2b: What about cumulative returns?

This is a tricky one. On the one hand, cumulative returns fall in the camp of point-in-time (typically inception-to-date) analysis. To be honest, the most important question is, arguably: have you outperformed since inception? But then I ask myself, what if the underperformance is due to one bad year, or the cumulative outperformance is due to one good year? Am I a good investor if I have one great year and then underperform the rest of the time? Am I a bad investor if I have one terrible year and add value the rest of the time?

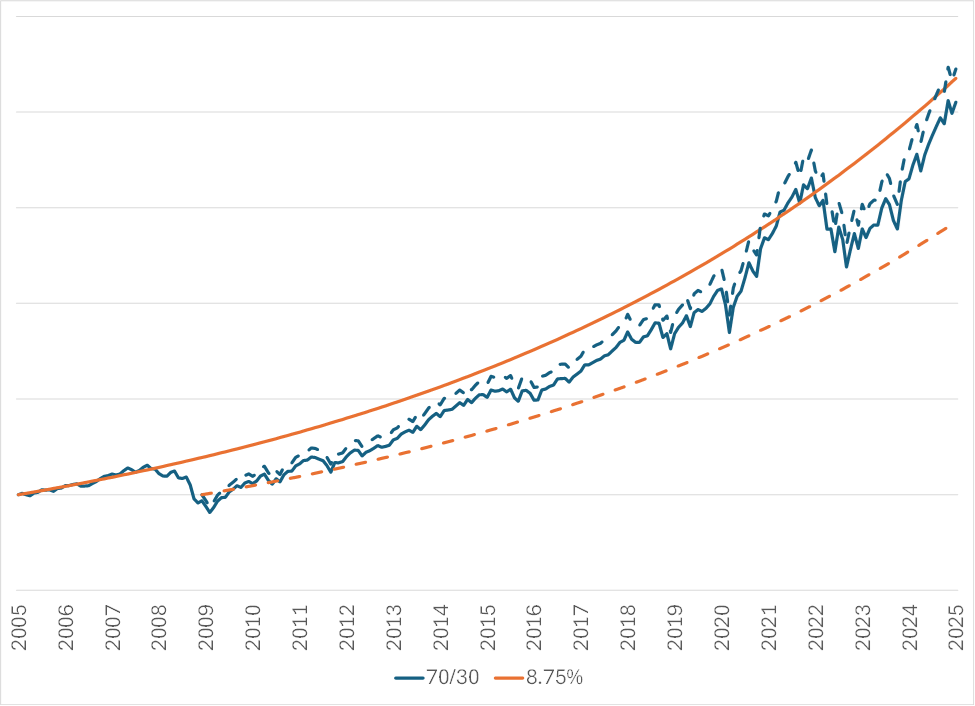

Cumulative Returns 70/30 vs Absolute Return Benchmark

The chart above illustrates one of my challenges with cumulative returns. When do you start? For an investment board, it may simply be when they hired the team. Consider the solid lines in the chart. A team hired in 2005 didn’t have a chance if their benchmark was an 8.75% return and they invested with a 70/30 portfolio. Things started off okay for the first few years, then the GFC happened, it took over a decade to finally catch up, and then the pandemic happened...

What about a team hired in 2009? They were shot out of a cannon and never looked back. Ultimately, cumulative returns are worth reviewing and are a piece of the puzzle, but I dislike the notion that simply looking at cumulative returns tells us all we need to know…To be continued.

About the Contributor

Steve Novakovic, CAIA, CFA is Managing Director of Educational Programming for CAIA Association. He joined CAIA in 2022 and has been a Charterholder since 2011. Prior to CAIA Association, Steve was a faculty member at Ithaca College, where he taught a variety of finance courses. Steve started his career at his alma mater, Cornell University, (B.S. 2004, MPS 2006) in the Office of University Investments. In his time there, he invested across a variety of asset classes for the $6 billion endowment, generating substantial insight into endowment management and fund investing across the investment landscape.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/

[1] Have you ever noticed that it’s totally fine to point out that a 70% or 80% allocation to U.S. stocks in the last two years crushed any other portfolio, but the idea of putting 70% or 80% of your portfolio into any other strategy is considered absurd? Seriously, is this not a double standard? Or are U.S. stocks a magical asset class that defy the need for any meaningful portfolio diversification? You know what would have crushed a 70% allocation to U.S. stocks? A 70% allocation to Bitcoin! But no one would ever view that as an acceptable portfolio allocation.

[2] 70% Russell 3000 TR, 30% Bloomberg US Aggregate TR