The People’s Bank of China launched two seemingly important products in 2010: the Credit Risk Mitigation Agreement and the Credit Risk Mitigation Warrant. I refer to them as “seemingly” important because they addressed a large issue in a vast economy, and did so in what seemed to many a commendably innovative way. Yet … maybe not so important? Because the products enabled through these systems haven’t really taken off.

A fine GARP presentation in December 2014 made a powerful case for why these products are “deadlocked,” and it is worthy of a review now. The latest news from the People’s Republic, after all, includes suggestions that the same bank is working to slow borrowing and face up to the high level of non-performing loans.

The Basics

The CRMA is a bilateral contract similar to what is known in much of the world as a CDS. One notable difference, though, is that the reference asset for a CRMA must be a bond or a loan, rather than a class of debt. The CRMW is a credit enhancement contract on publicly traded debt, sold by qualified financial institutions and freely tradeable. The term “CRM” is used for the two generically.

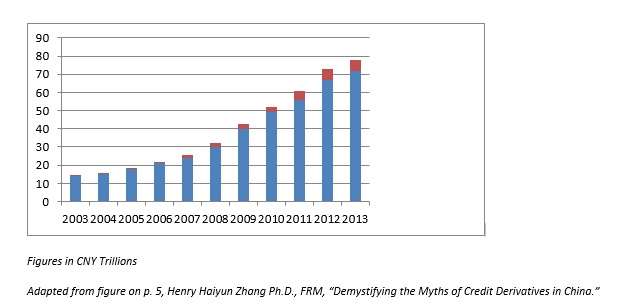

How big is the market for risk mitigation? The graph below is adapted from one presented by Henry Haiyun Zhang, in the GARP presentation mentioned above. It shows the loans outstanding (the blue bar) in china measured in trillions of yuan, as well as the credit bonds outstanding (the rust bar) over an 11 year period. This graph indicates both that the market that CRMs might help hedge has grown explosively and that most of the market consists of bank loans, not bonds.

The compounded annual growth rate for the past decade as Zhang made this presentation was 16% for loans outstanding and 52% for the credit bonds.

Given that, Zhang wonders why the potentially multi-trillion yuan market has been “anemic since inception.”

The gist of this presentation was that four myths have grown up around China’s market, and that Zhang wanted to disabuse his audience of all of them. He called them the myths of implicit guarantee, of capital relief, of risk prevention, and of CDS prospect.

The myths address three perfectly good questions: what’s deadlocking the market? (Implicit guarantee and ignored capital relief are the wrong answers to this one); is the product alteration beneficial? (the myth of risk prevention addresses this one); do credit derivatives have a future? (CDS prospect).

The Right Answer to Each Question

The logic of the mythologists is that the implicit guarantee for bonds has meant there haven’t been any default losses, so nobody wants to spend any money ensuring against such an outcome. The case of the bailout of Shanghai Chaon Solar Energy Science, a maker of solar equipment, seemed to bolster this mythology.

But Zhang thinks this confused. After all, CRMs on their face aren’t solely about bonds, they also protect loans, and loans constitute the “lion’s share of credit assets” in China. Nobody contends there is an implicit guarantee for loan losses, indeed such losses had been on the rise over the two years before this presentation. So an absence of any work for hedging instruments can’t be behind the CRM stalemate after all.

The deadlock itself is real, though, and Zhang contends that a better explanation for it is the banks are “disinclined” to use their loans as reference obligations, and that this disinclination itself arises from “the CRM product alteration on underlying obligations,” precisely what had been hailed just four years before as an innovation.

The second myth offers a second bad explanation for the deadlock, that is, that parties with credit risk in China have failed to understand the capital relief function of CRM. Zhang thinks this a misguided reading of the situation, too. Parties haven’t failed to realize this function; they have quite accurately realized that the capital relief function is very limited.

As Zhang put it, the “CRM product alteration diminishes CRM’s hedging effectiveness and could invalidate capital relief.”

Drawbacks of Transparency

This brings us to the second question, and the third myth. The question is whether the product alteration has been beneficial. The myth is that by abandoning the market standard for credit default swaps, that they cover all obligations in a category, and by adopting a model that covers reference obligations only, China increased transparency, making easier regulators’ gauging of the trading intention of market parties, and that this facilitated risk prevention.

But Zhang sees this as part of the problem, not part of the solution. “If a transaction lays bare a market player’s trading intentions, the player may choose to stay away from the transaction.” Indeed, distrust of the sort of transparency involved “may be a key reason why the market has hitherto given the cold shoulder to CRM.”

The fourth and final myth then is “CDS prospect,” that is, the notion that China has successfully moved beyond the international CDS model. To the contrary, in Zhang’s view, “CDS has a key place in the financial value chain.”