By Hossein Kazemi, PhD, CFA, Senior Advisor at CAIA Association, and Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CIPM, Associate Director, Content Development at CAIA Association

“There are at least two kinds of games. One could be called finite, the other infinite. A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

This is the opening paragraph of a book titled “Finite and Infinite Games, written by James Carse (1986, Free Press). While the book has nothing to do with investment management, one of its many conclusions can be applied to the management of endowment portfolios. According to Carse, finite games are played within certain boundaries, while infinite games are meant to break boundaries. Perhaps that is why investment managers of endowments have been pioneers in developing new approaches to portfolio management and asset allocation. No one has played a more critical role in breaking those boundaries and introducing new ideas in the field of investment management than David Swensen and his Endowment Model.

A Background on Endowments

Endowments and foundations are tax-exempt and charitable organizations that rely on permanent pools of capital to fund their activities. Institutions such as colleges, universities, hospitals, museums, scientific organizations, charitable entities, and religious institutions own these pools of capital. When well-funded and well managed, an endowment can provide a perpetual annual income stream to the organization, while maintaining the real value of its assets into perpetuity.

The long time horizon of an endowment may give the impression that managing its assets should be relatively easy. However, an endowment’s portfolio is not an unrestricted pool of capital that can be managed using a single strategic asset allocation model developed as a part of the investment policy statement. The pool of capital consists of many smaller pools of capital with their own restrictions stemming from terms sets by the donors and the institutions

Also, there is a well-known tension and trade-off between increasing spending rates to take care of immediate needs and increasing investments to ensure the survival of the institutions. This tension has been quite visible during the COVID-19 crisis, as many university endowments are struggling to develop a sensible policy to address it. Clearly, there needs to be some increase in spending to take care of significant gaps in operating budgets, but the uncertainty regarding the depth and duration of the crisis makes it impossible to determine how to use the endowment’s capital to fill that gap.

The Endowment Model

Due to their perpetual nature and long-term objectives, endowments are able to maintain rather aggressive asset allocations relative to other institutions. A long time horizon combined with a low spending rate allows endowments the ability to allocate little capital to cash-like and fixed income securities while allocating significant capital to alternative investments and illiquid securities.

In Yale’s endowment portfolio, for example, Swensen allocated very little to fixed income, instead opting to own equities and real assets. While there are several arguments against owning bonds in an endowment portfolio, the most glaring rationale could be future return expectations. Starting bond yields tend to be a good predictor of future returns (ex-defaults), and most bond yields sit at record lows (or are negative). For a perpetual entity, there is a certain opportunity cost to investing in safer asset classes like fixed income, making risk-on asset classes far more attractive.

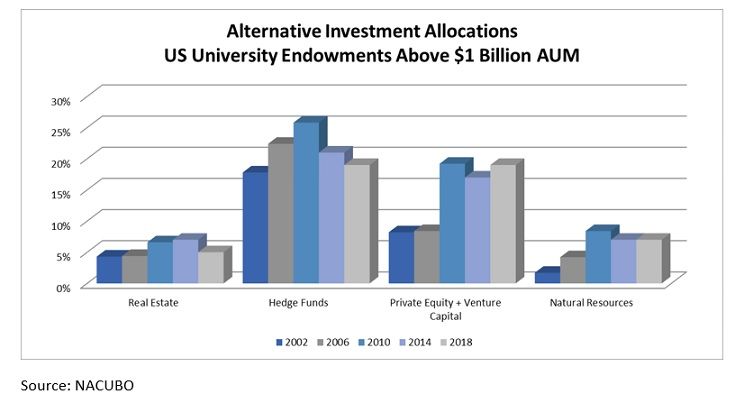

While fixed income tends to be a smaller portion of the portfolio, endowments have historically allocated significant capital to alternative investments. The chart below displays NACUBO data for the average allocation to alternative investments for large endowments (over $1 billion). As of 2018, approximately 19% of large endowment portfolios were allocated to hedge funds, 5% to real estate, and 7% to natural resources. What’s even more interesting is the massive jump in private equity/venture capital allocations, which jumped from 8% in 2004 to 19% in 2018.

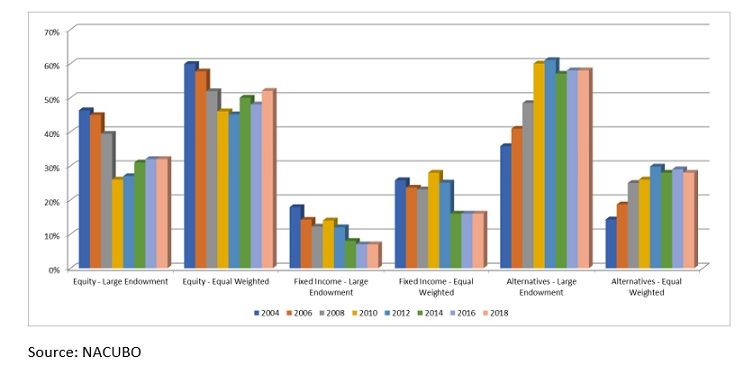

These large allocations to alternative investments are not consistent across all endowments. While the average endowment has increased their allocations to alternatives over time, smaller endowments have significantly less exposure to alternatives. The chart below compares the average total allocation to equity, fixed income, and alternative investments across large endowments ($1 billion+) and all endowments equally-weighted. There is very clearly a larger allocation to alternatives in large endowments relative to the rest of the endowment universe.

Why might this be the case? Using NACUBO performance data, larger endowments have outperformed smaller endowments on average historically (though that gap has narrowed as alternatives have struggled on an absolute return basis the past decade), so why aren’t small endowments piling into some of the same investments? There may be several reasons for the advantage large endowments enjoy over small endowments, such as more effective manager research, access, or ability and willingness to accept liquidity risk.

Regardless of the reasons, endowments still play the infinite game, and endowments of all sizes have been relatively eager to explore and expand their allocations to alternative investments,from hedge funds to private equity to timber to farmland. All of these investments are illiquid, complex, and require bulky investments. Therefore, many small and medium-size endowments either choose to avoid them or outsource the investment management of the assets.

The Endowment Replication Portfolio

In early 2000, the first author and Thomas Schneeweis developed replication methodologies that could be used to track private asset classes such as hedge funds. These programs were implemented by some financial institutions to manage cash and make medium-term investments. A few years ago, they decided to take the model, and with some significant changes, apply it to endowments.

Since endowments report their performances only once a year, one does not have enough data points to create dynamic asset allocations similar to those developed for hedge funds. As a result, it was decided to create an intermediate uninvestable benchmark and then create an investable portfolio that would track the uninvestable benchmark. The initial results and the descriptions can be found here and here.

In short, the approach uses a large set of investible and uninvestable indices to match the annual returns on large and medium-size endowments. Then, a machine learning algorithm is used to create a parsimonious investable version of the index using higher frequency returns on liquid ETFs.

Each quarter, we publish the composition of the replication portfolio on CAIA Association’s website. Usually, the composition of this replication portfolio changes slightly from quarter to quarter. However, there are times that endowments make significant changes to their asset allocations, which have led to similar changes in the replication portfolio’s allocations.

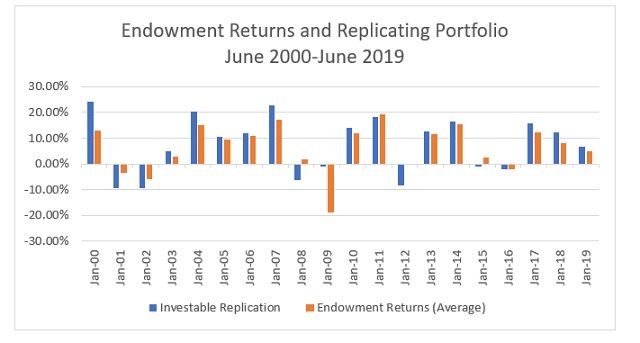

The results have been promising and robust. Below is a chart displaying the annual report on university endowments and the replicating portfolio (the replicating portfolio has outperformed the endowments’ performance by 2.8% per year gross of fees since we started this program in 2017).

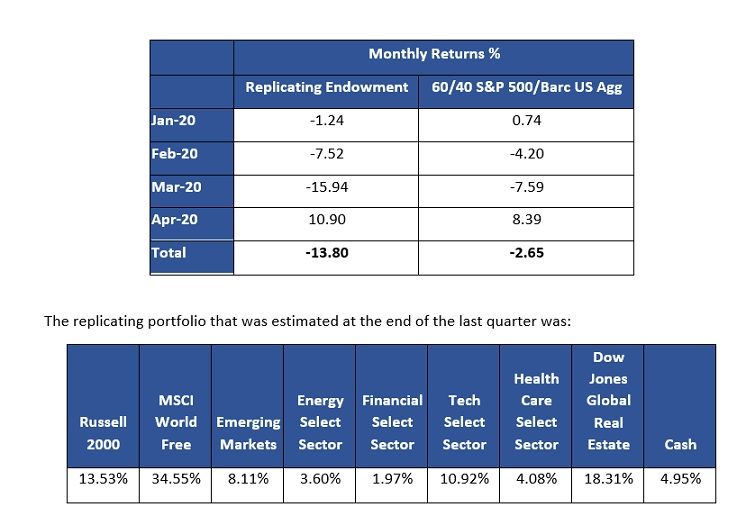

Another benefit of the approach is that it allows us to get a good idea of what is happening to endowment portfolios before they report their performance figures later in the summer. For example, below is our estimate of their performances for January-April 2020. The typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio is included, as well.

We expect the endowments to report returns that would indicate a smaller loss than 13.8% as they have large allocations to illiquid investments and mangers of those asset classes are slow in marking them down to reflect true market conditions.

How Might This Be Used In Practice?

The replication portfolio not only provides insight into how endowment managers allocate their capital over time, but it also provides an interesting use case for smaller endowments and individual investors. Smaller endowments have historically underperformed larger endowments but, by reverse engineering The Endowment Model and implementing a replication portfolio with and low cost and liquid solution, they might have a chance at closing the gap between their larger counterparts.