Part 1 of a multi-part series: The Role of the EU, National Governments & Local Authorities By Christos Angelis, CAIA - Director at Masterdam INTRODUCTION In light of the exciting developments in the European Union regarding the European Green Deal (EGD)[1] presented in the end of 2019, it would be useful for both real estate investors and developers to have a practical overview of EU’s environmental policies and their expected impact on European real estate. In order to make the analysis more applied, we will deliver a series of articles from the standpoint of different stakeholders:

- Government

- Real Estate Owners

- Tenants

- Developers

- Financiers

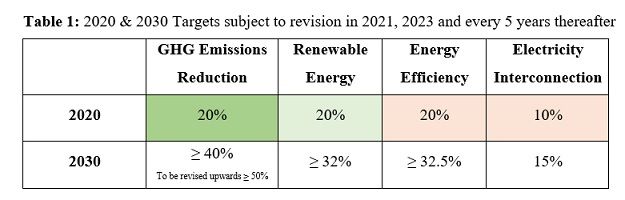

This article is focused on the role of the government at EU, national and local level. We will start with a commentary on the rise of Green political powers in Europe followed by a summary of EU’s current environmental policies and the newly proposed EGD. Subsequently, we will focus on real estate in the context of EU’s current environmental policies and discuss what is new under the EGD. Finally, we will discuss the implementation of these policies focusing on the tools available to the EU and member states in order to facilitate this process. GREEN IS THE NEW RED The Dam Square in Amsterdam has historically been a hot spot in the Netherlands for peaceful demonstrations about current political and social issues. In recent years, the interest in environmental causes has increased exponentially, which is evident in the number of “green rallies” organized in the Dutch capital. Global warming, animal rights, protection of sea life, and other relevant environmental topics have attracted the attention of the public and mass media throughout Europe. These issues have particularly resonated with younger generations embarking on a crusade of environmental activism on social media and beyond. This major shift of priorities from relevant economic and governance issues that dominated the political debate in the past to saving the planet did not go unnoticed by European politicians. Green is without a doubt the new Red. Green political parties with environmental agendas are on the rise throughout the continent. In the 2019 German national elections, the Bündnis 90/Die Grünen was the second largest party winning 20.5%[2] of the total votes compared to only 10.7% in 2014. In other European countries such as Austria, UK, Ireland, The Netherlands, Sweden and Finland, voters’ support to Green Parties continues to rise. There is also a plethora of examples in local elections where Green candidates were victorious over rival candidates supported by dominant political parties. A recent example is the 2020 municipal elections in France where Les Verts won in major French cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier, Bordeaux, and Strasbourg. However, the Green wave is less prominent in Eastern and Southern Europe due to lower awareness and primary focus on economic issues. It came as no surprise to political analysts that the Greens/EFA group secured 74 seats out of the total 751[3] in the 2019 European parliament elections (42% increase compared to 2014), becoming an emerging political power in Brussels. With young European voters supporting Green political agendas, it is a matter of time to witness a further increase in the representation of Green parties at EU, national and local council level. This political mega trend is expected to facilitate the introduction of stricter environmental policies at EU level and smoothen the implementation process at both national and local level. GOOD INTENTIONS ARE NOT ENOUGH The EU has historically been a champion for the environment and a major catalyst for environmental policy change at member state level. The EU has committed to all relevant international environmental agreements such as the UNFCCC[4] in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the subsequent Kyoto Protocol[5] in 2005 and the Paris Agreement[6] in 2016. According to the latest update in Q1 2020, the EU member states have already met the Kyoto commitments for the period 2008-2012 and they are on track to meet them commitments for the period 2013-2020[7]. Apart from the Kyoto commitments, the EU has introduced even bolder environmental policies namely the 2020 Targets[8] in 2008 and the 2030 Climate & Energy Framework[9] in 2014. The following table summarizes EU’s average targets. The percentage changes in GHG emission targets refer to 1990 levels. Energy efficiency refers to the reduction of energy consumption compared to 2007 projections for 2020 and 2030. The percentages of renewable energy and energy network interconnection refer to their share of the total.  Based on Q1 2020 figures, the EU has on average already met their GHG emissions target for 2020 and it is on track to meet the renewable energy target. However, the energy efficiency target for 2020 might not be achieved assuming normalized levels of energy consumption i.e. excluding Covid-19’s temporary effect. The same underperformance is evident in electricity network interconnection between member states. TIME FOR ACTION: THE EUROPEAN GREEN DEAL In December 2019, the EU announced its most ambitious environmental plan to-date namely the European Green Deal[10]. It entails a roadmap with a list of actions in order to turn the EU climate-neutral by 2050 and transition to a modern, sustainable and circular economy.

Based on Q1 2020 figures, the EU has on average already met their GHG emissions target for 2020 and it is on track to meet the renewable energy target. However, the energy efficiency target for 2020 might not be achieved assuming normalized levels of energy consumption i.e. excluding Covid-19’s temporary effect. The same underperformance is evident in electricity network interconnection between member states. TIME FOR ACTION: THE EUROPEAN GREEN DEAL In December 2019, the EU announced its most ambitious environmental plan to-date namely the European Green Deal[10]. It entails a roadmap with a list of actions in order to turn the EU climate-neutral by 2050 and transition to a modern, sustainable and circular economy.

- Zero net emissions by 2050 (Stricter Targets & Aggressive Implementation)

- Economic growth decoupled from the use of natural resources (Green Innovation)

- No person and no place left behind (Technical & Financial Support)

EGD endorses investments in technology and innovation to facilitate the transition to a climate-neutral economy. It will provide technical assistance and financial support of at least € 100 billion through the Just Transition Mechanism[11]over the period 2021-2027, which is expected to stimulate total investments of over € 1 trillion from the EU, national governments and private investors. These initiatives could potentially kick start the engines in the aftermath of Covid-19 and turn the problem into opportunity by modernizing the economy and creating thousands of jobs. Structural changes in the European energy and industrial sectors through decarbonization and environmental-friendly technologies could be a game changer. Buildings, transportation, agriculture and waste have been identified as lower hanging fruits with concrete initiatives under the proposed EU plan. The aforementioned sectors are not covered by the European Emissions Trading System although they account for circa 55% of total GHG emissions. Therefore, emission reduction is only possible by drastically improving energy efficiency through investments. In March 2020, a Draft European Climate Law[12] was presented to member states for public consultation. The document provides more details about the action plan under the EGD and its implementation process. In particular, it proposes the revision of the 2030 targets regarding GHG emission reduction from 40% to 50-55% with further revisions in the future depending on progress. Furthermore, the intention is to create a predictable business environment for companies and investors in order to stimulate a wave of green investments. After the public consultation and negotiations with member states are concluded, the proposal will become EU law in the course of 2020. As a result, the EU will have higher oversight over implementation compared to the current policies and it could steer the national governments towards the right direction. REAL ESTATE: THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Buildings have undoubtedly been the thorn in EU’s side regarding its environmental policy due to their massive contribution to GHG emissions and energy consumption. The following statistics regarding the profile of European real estate put things into perspective:

- 40% of energy consumption from buildings

- 36% of GHG emissions from buildings

- 35% of building stock over 50 years old

- 75% of the building stock is energy inefficient

The EU has not been idle in terms of environmental policies on real estate. The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive[13] (EPBD) in 2002 and the subsequent updates in 2010, 2012 and 2018 have put in place progressive restrictions for both existing and new buildings. The goals of the EPBD are the following:

- achieve a highly energy efficient and decarbonized building stock by 2050

- create a stable environment for investment decisions

- enable consumers / businesses to make informed choices to save energy and money

It is evident that the EPBD is in line with the goals of the EGD. However, the current policies provide high flexibility to member states since they are responsible for their national plans and have discretion over implementation. In my opinion, EPBD had a profound impact primarily on new development projects changing the mindset of both developers and investors. For existing properties in need of renovation, EPBD did raise awareness but we still have a long way to go towards practical implementation. Only 1% of the building stock is being renovated every year whereas 75% of the building stock has low energy efficiency. Although the real estate sector was able to reduce GHG emissions by more than 20% since 1990, it performed poorly in reducing energy consumption. EGD has identified the real estate sector as an integral part of the envision plan. It proposes the start of a major Renovation Wave[14] across Europe focusing on improving the energy efficiency of buildings in line with the principles of circular economy. The construction industry generates approximately 9% of EU’s GDP and provides approximately 18 million direct jobs. This so-called renovation wave could provide a significant boost to the economy, which is desperately needed after Covid-19. The target is to at least double the current renovation rate per annum for private and public buildings prioritizing on social infrastructure. Furthermore, renovation projects should make use of environmental-friendly materials, building techniques and relevant technology for energy savings and performance monitoring. The EU also intends to bring together owners, developers, professionals and local authorities in order to promote energy efficiency investments, pool renovation efforts into large blocks for economies of scale and develop innovative financing solutions. Finally, it will provide technical and financial support for energy efficiency initiatives by member states. The requirements for new developments are already covered by the EPBD since 2010 with a major target step-up in 2021. From 31 December 2020, all new projects must deliver nearly zero-energy buildings[15]. This was applicable for public newly developed buildings since 31 December 2018. Under the EGD, we should expect more applied restrictions regarding energy efficiency performance and monitoring post project completion. THE CARROT: SUPPORT & FINANCING TECHNICAL SUPPORT The EU is committed to provide technical support to national governments and create open platforms where all relevant stakeholders i.e. local authorities, owners, developers and service / installation providers can collaborate. This commitment looks promising on paper but implementation can be rather challenging. Given the complexity of energy efficiency and renewable energy installation works, local authorities supported by the EU and national governments will need to intensify their efforts in increasing awareness on the possibilities of retrofit projects through organized marketing campaigns. Moreover, local planning and urban development agencies will need to be engaged in the process through training sessions in order to be in a position to provide technical support. Relying solely on the guidance of service providers and installation companies with purely commercial incentives might not be prudent for owners and developers. Checks and balances need to be established in order to promote accountability. FINANCIAL SUPPORT EGD will pledge at least € 100 billion through the Just Transition Mechanism until 2027. Although it is unclear how much will be allocated to real estate, we expect that the lion’s share would go towards social infrastructure owned primarily by the government. Social infrastructure includes schools, universities, hospitals, elderly homes, prisons, sport centers, pools, libraries, museums and social housing. From the perspective of national governments and local authorities, renovating such properties provide maximum political exposure since these initiatives typically receive media attention. Subsidy programs for energy retrofits might be introduced or extended if there are already in place including the installation of solar panels primarily for residential buildings. These programs could be run directly from the local authorities or in co-operation with commercial banks and installation companies. It is yet to be seen whether commercial real estate owned by private landlords such as REITs, PERE funds and private property companies will receive any form of financial support for retrofit projects. There are ideas from member states to potentially provide tax incentives in the form of tax exemption from VAT for retrofit works, which is important for residential buy-to-let owners or commercial owners with VAT-exempt tenants. THE STICK: MONITORING, TARGETS & RESTRICTIONS EPCs MANDATORY Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs)[1] were introduced by the EU in 2002 under the EPBD and they were further improved in subsequent updates in 2010, 2012 and 2018. EPCs constitute a powerful tool in measuring the energy efficiency of buildings. They support member states in gathering data regarding the energy profile of their national real estate stock. Based on the available data and analyzed trends, member states are better informed in order to focus their efforts and policies on specific real estate segments or geographical areas. The EPC evaluation process is conducted by specialized professionals and the certificates are typically valid for 10 years. The process of obtaining an EPC raises awareness and educates real estate owners regarding a) the current energy efficiency profile of their properties and b) potential initiatives that could increase their EPCs resulting in substantial cost savings. In all member states it is now mandatory to include an EPC in every lease and sale transaction. This is a major restriction making EPC a necessity in every commercial deal. The level of EPC can also be used as a concreate reference point in order to introduce restrictions on real estate. RESTRICTIONS ON LEASING Using EPCs as a reference point, EU member states have introduced restrictions on leasing space in energy inefficient buildings. The government and other government-backed agencies are also leasing sizable space such as offices, warehouses and others from private real estate owners. As a tenant with environmental awareness, the government can set higher requirements in terms of energy efficiency for choosing space, setting a good example for other tenants. For example, the Dutch government is not allowed to lease space in buildings with an EPC below C level. Similar leasing restrictions are expected to become effective in due course for private tenants throughout the EU. These measures will effectively make energy inefficient buildings commercially obsolete unless they are renovated by their owners. This will have a negative effect on real estate valuations for energy inefficient buildings since current and future owners will need to allocate significant Capex. It is clear that the higher the EPC requirements, the wider the impact would be on the real estate market. RENOVATION WAVE The current annual building renovation rate in the EU is merely 1% on average. EGD is targeting to at least double the renovation rate in order to meet its long-term objectives. The government is typically one of the major real estate owners if we take into consideration social infrastructure. Public buildings are highly suitable for implementing green initiatives and collecting performance data for future use. Since the government as a real estate owner and operator has a longer-term horizon, the long-term nature of energy cost savings is a good match from an investment perspective. Under the EPBD, member states are required to refurbishment 3% of their government owned real estate annually. On the other hand, there are no concrete nor binding national targets for renovating privately-owned real estate apart from the indirect effect of EPC leasing restrictions. We expect that the EGD will put significant pressure on member states to create and implement long-term plans for making buildings decarbonized by 2050, which by default will include both public and private real estate. RESTRICTIONS ON NEW DEVELOPMENTS Under the EPBD, all new development projects should be nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEB) starting 2021. Effectively, new projects that don’t meet the requirements will not be granted building permits. This is an important factor for developers when creating their designs and development budgets. In order to achieve NZEB status, high quality materials and modern building techniques are required. Furthermore, the integration of technology such as LED lighting, smart sensors, efficient heating / cooling systems and space user analytics can contribute greatly to the building’s energy efficiency. Finally, building roofs and potentially other underutilized spaces could be used for the installation of solar panels, contributing to the generation of clean energy. EGD is expected to have a more critical look into the development process through the prism of circular economy and impose additional monitoring post project completion. For example, creating sustainable buildings through ground-up developments is definitely a step forward. However, maintaining parts of the existing buildings would shorten the construction period, resulting in lower emissions. Also reusing existing materials from buildings would contribute to the circularity of the economy. The same applies for the new materials and building techniques used during construction. Creating a sustainable building without the possibility to disassemble and reuse the materials or make it easier to retrofit when the building reaches the end of its economic life may defeat the purpose. Lastly, investing in cutting-edge technological systems for energy performance monitoring and savings, which are difficult to maintain, upgrade or replace, would also be considered counter-productive. CONCLUDING REMARKS Under the European Green Deal, we expect that the real estate sector will concentrate the interest of the EU and national governments since it could contribute greatly towards the three main pillars of EU’s climate change plan. Stricter regulations and more aggressive implementation are expected coupled with higher technical and financial support. Private investments can play a significant role in this process. However, it is still unclear what form of support will private real estate owners receive, if any. There are three major issues regarding real estate that make the implementation of environmental measures challenging. Firstly, stakeholders in real estate have materially different incentives and horizons. Secondly, retrofit projects require high upfront investments and follow-on financial commitments for maintenance whereas annual benefits to stakeholders are rather small and spread over a longer period of time. Thirdly, the level of sophistication in real estate markets across EU varies significantly due to structural and economic differences. Therefore, we should expect major deviations in performance between member states. In the next article, we will discuss the European Green Deal from the perspective of real estate owners and prospective investors. CHRISTOS ANGELIS, CAIA Director at Masterdam Chris is a real estate corporate finance advisor at Masterdam and the Head of CAIA Netherlands. As an investment professional, he is committed to a better urban environment by supporting real estate innovators. He has more than 12 years of experience as a portfolio manager and investment advisor in European real estate markets. Chris holds a MSc in Finance & Investments from Rotterdam School of Management (cum laude) and has attended executive education courses at INSEAD Business School. He has been a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) Charterholder since 2012 and a member of CAIA Netherlands executive committee since 2015. [1] EU [2] German Government [3] EU [4] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [5] Kyoto Protocol [6] Paris Agreement [7] Kyoto Commitments Update [8] 2020 Targets [9] 2030 Climate & Energy Framework [10] EU [11] EU [12] EU [13] EU [14] EU [15] EU

Interested in contributing to Portfolio for the Future? Drop us a line at content@caia.org