By Jamie Ebersole, CFA, CFP, CEO, Ebersole Financial, LLC

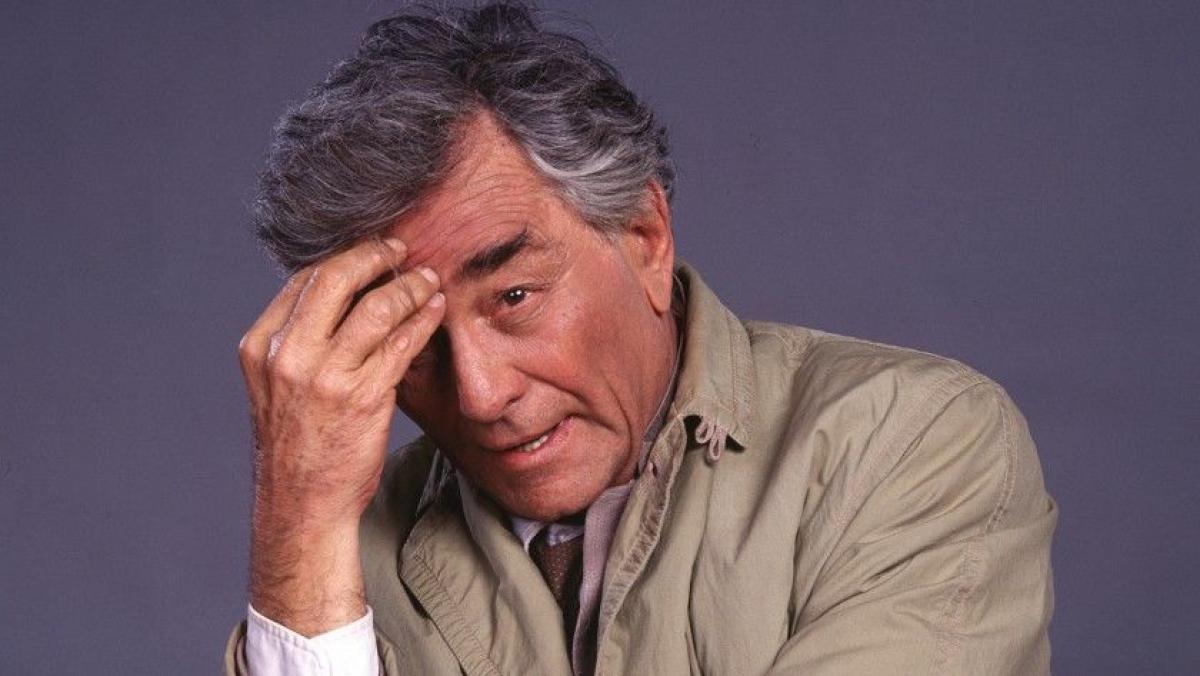

There is no shortage of information out there about due diligence on private assets and managers of private funds. When I started in the business many years ago, I remember receiving a research paper on the topic from Goldman Sachs, which amounted to a very long checklist of questions to ask to help vet a manager. As someone starting out in the industry, this was a great tool, but as I advanced in my career and met hundreds upon hundreds of managers in thousands of meetings, it became clear that there was much more to the due diligence process than could be captured in a checklist. As one of my mentors liked to say, "...our job is to be like Columbo, always looking behind the obvious facts to uncover the truth." While we weren't always prepared with a gotcha question to get to that truth, it was usually the diligence occurring outside the lines that yielded the best insights. With this series of articles, I will aim to add a different perspective to the academic literature on the topic by relating lessons that I have learned in the trenches. I will also provide some observations on interesting insights I have found through the thousands of human interactions I have had interviewing general partners (GPs).

The world of due diligence is very nuanced. Some institutional investors are short-staffed and are looking to fill out a checklist that they can then put into a folder as proof that they conducted a process if questions arise in the future. Some rely very heavily upon the information from the GP in its current form accepting it without checking it for accuracy. (One pet peeve of mine is that all managers who are fundraising tend to show a top-quartile track record during the fundraising process, although we know that not everyone can be top-quartile. But, if only top-quartile managers can raise funds, then all managers will be top-quartile.) Some investors tend to boil the ocean and analyze anything and everything about a manager, without necessarily taking the time to focus on what the key decision criteria should be. They can recite facts about deals and minute details about where the GPs kids go to school, but they don’t have any insights on the culture of the firm, how investment decisions are made, or if the people and processes at the firm are suited to generating the types of returns they see in the PPM over the long term. This is where we need to channel our inner Columbo to ferret out what is important and dig deep enough until we can reasonably answer the question as to whether the alignment between all the various business elements in the firm supports an investment or not. Taken individually, track record, team, culture, operating experience, tenure, etc. are not sufficient to provide us with a complete enough picture to make a sound decision.

With this in mind, how do we do this effectively given that access to managers is sometimes difficult and intermediated, information is limited, and timing is short? To start, let’s focus on a few lessons surrounding track record and returns. This is by no means an exhaustive coverage of the topic, and I will likely return to this topic—and others related to due diligence—in the future.

For many GPs, especially those raising a first or second fund, or those coming off of a poor performing fund, showing top-quartile performance is key to fundraising success. Rudimentary analysis of the track record should be able to highlight risks to the top-quartile potential of the firm. We all know to look for one investment return (concentration) that drives results, or distortions from time-zero IRRs or one quick flip that crystallizes a high IRR early in the life of the fund. But what else should we consider? One item that helps get to the issue of integrity is the aggressive nature of marked-to-market returns. A track record that is completely dependent upon future valuations is not uncommon for managers early in their life cycle. But, when those valuations are uniformly and artificially high, this raises questions about the honesty of the firm and should open other lines of inquiry. One manager stands out in my mind for highlighting their business growth accelerator model, which showed that uniformly through their proprietary business improvement processes, all of their companies would generate 3.0x – 3.5x multiples on invested capital. Needless to say, years later when the results came in, returns were nowhere near this level. And they had even managed to destroy value in companies that were outperforming this internal benchmark at the time of the fundraise. This type of hyperbole raises a few questions about the organization. First, no fund I have ever seen has a uniform distribution of returns. There may be a few out there, but not many. So, is the GP delusional or exceedingly optimistic? Dishonest? Just marketing? In hindsight, probably a bit of each, but the red flag should have raised enough questions about the organization to move them down the list of potential investment options.

Second, if things seem too good to be true, they probably are. If the future expected returns do not follow the normal patterns we see in the private equity world, and there is no good reason to believe that this fund should deviate from that pattern, then hoist that red flag. Venture Capital funds and small private equity funds with impeccable timing may have a fund or two that have outlier type performance. But, most seasoned funds do not. As we know, aside from time-specific anomalies we can’t know in advance, larger funds tend to underperform smaller funds and those raised after a capital contraction in the markets tend to outperform those raised in the latter stages of a cycle.

Finally, try to match the story of the GP with the actual performance history of the fund and the team. For me this means a few different things. One, look at where people came from. A self-made entrepreneur who is starting a fund after exiting a successful bootstrapped company will tend to be much more optimistic in terms of an ability to generate outsized returns than a former investment banker. The investment banker will likely still overestimate his or her skills and abilities to generate outsized returns, but they will be more muted since they understand the institutional framework better. Two, look for investments that they made that don’t fit with the story they are telling. Having data from their prior fundraising process and speaking with early investors can help clarify this. Data mining is rampant in the world of asset management. Explaining away investments that don’t “fit” with the current focus of the firm is a fallacy of which to be mindful. The usually underperforming investments were a result of the same process that generated the “good” returns in the “new” targeted areas of investment. At a minimum, you need to understand what was wrong with the prior investment process, how it was fixed, and if it was a personnel issue, how the hiring mistake was made and how the hiring process was changed to fix it. GPs will have answers to these questions, but ultimately, they need to own the whole track record and not try to walk away from it. You will be the judge as to whether their explanation makes sense. Firms that mine data in this manner usually move to the end of my line as it will take at least one fund cycle (if not longer) with the “new” team and strategy to see if the changes were effective. Since private market investments rely upon deep networks and domain expertise, firms changing strategy frequently will be at a disadvantage compared to funds focusing exclusively on a niche. Chasing returns and hot market segments tends to lead to disaster over the longer term.

There are a lot of pressures on limited partners to “deploy” capital in a hot market environment. Nevertheless, taking the time to complete a thorough due diligence process is very important to avoid making bad decisions. Private equity investing is a long-term business, and while it may seem otherwise in the heat of the battle, you almost always get another bite at the apple. Do good work, don’t compromise on your standards, and build good relationships, and you will be well on your way to success. And hopefully, some of these insights will help you get there.

These are my insights and views alone and should not be taken as reflective of the views of anyone other than me. In this regard, I take responsibility for everything said here. I would also love to hear from you about your experiences in the trenches.