By Steve Novakovic, CAIA, CFA, Managing Director of Educational Programming, CAIA Association

In Innovation Unleashed: The Total Portfolio Approach CAIA Association highlighted governance as one of the four key dimensions of the Total Portfolio approach (TPA). In the TPA model, the governance structure delegates most authority from the board to the investment team. The one decision not delegated to the investment team is the portfolio objective. This objective informs portfolio construction and investment decisions made by the investment team, effectively acting as guardrails or the North Star for the portfolio. Understandably, the primary fiduciaries of the fund should take great care and responsibility in determining long-term needs for the portfolio. This decision process not only serves to define the profile of the investment portfolio, but also to identify a means by which to evaluate the success of the investment team.

For most institutional investors, the portfolio objective is a target return. For some, this may be an absolute return objective (e.g., 6% per year). For many others, it’s a relative return objective. For example, many corporate pension plans will choose a target return that’s informed by the underlying pension liabilities. For endowments and foundations, a common goal is to preserve purchasing power, requiring a return objective that incorporates the payout, inflation, and expenses. For others, a common target is to exceed the 70/30 (or 60/40) stock/bond portfolio.

Risk as an Objective

Until being exposed to TPA, I had not given much thought to the selection of the portfolio objective. It seemed logical to construct a return-based objective to ensure the sustainability of the portfolio. However, while speaking with firms adhering to the TPA model, I discovered there is a (small) universe of investors whose portfolio objective is risk-based. After nearly a year of contemplation, I’m sold. I understand it can be sensible to match pension return targets with liabilities, and for E&Fs to wish to maintain real value of the principal. However, I see great merit in a risk objective, and even for pension plans and E&Fs, it may be helpful for the board to think more in terms of risk objectives than return objectives.

Ultimately, the board’s greatest concern should be risk. For pension plans, the greatest risk is shortfall risk. For perpetual investors, such as E&Fs and Sovereign Wealth Funds, the greatest risk is maintaining purchasing power (and generating real portfolio growth). The “return” objective for those investors is effectively a risk objective (i.e., the return needed to minimize shortfall risk, the return needed to maintain purchasing power). For other investors, why not define a risk objective rather than a market-based return objective or an absolute return objective?

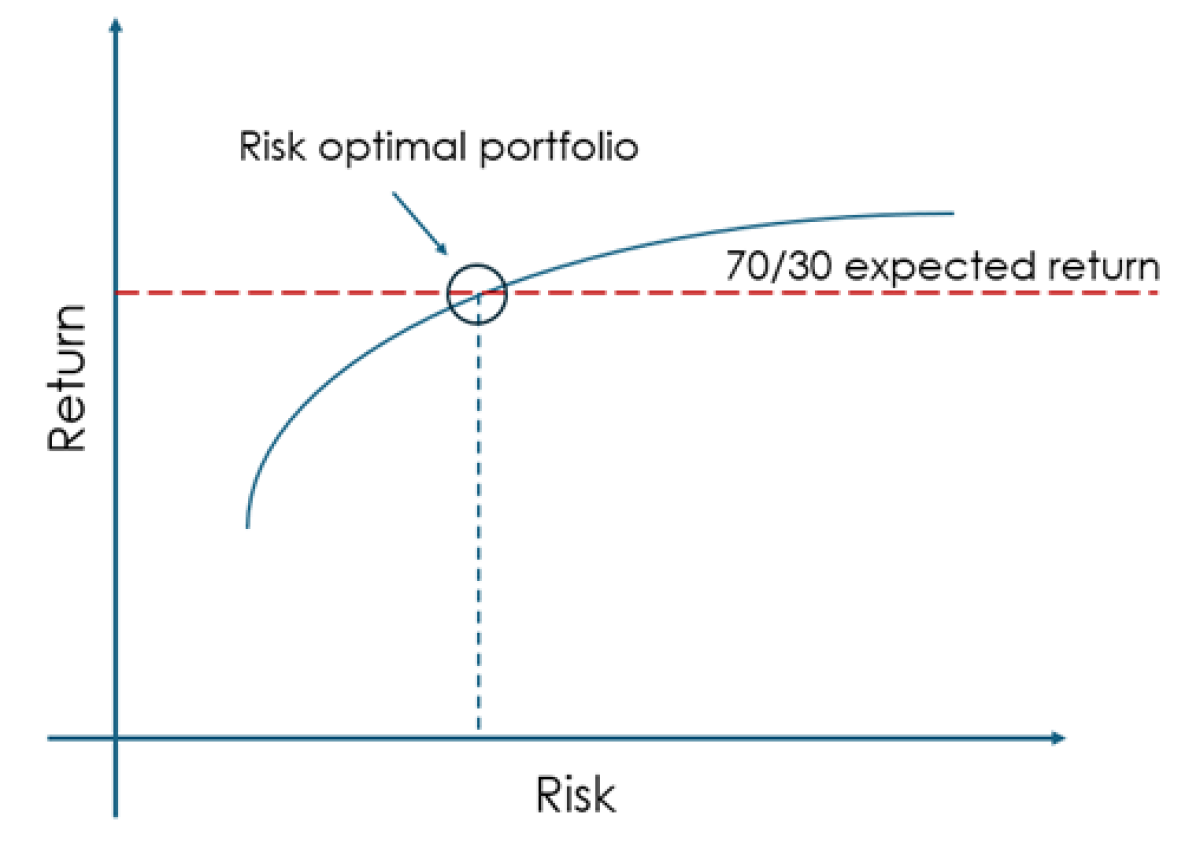

As an investor, our goal should always be to optimize (i.e., maximize) return for a given level of risk. When boards define a return objective, are they ensuring that the investment team is taking the least amount of risk needed to meet the return? As shown below, there are numerous portfolios that arrive at a 70/30 expected return, but only one does so in a risk-optimized fashion (i.e. lowest possible risk).

Example of an Efficient Frontier

The Merits of Targeting Risk

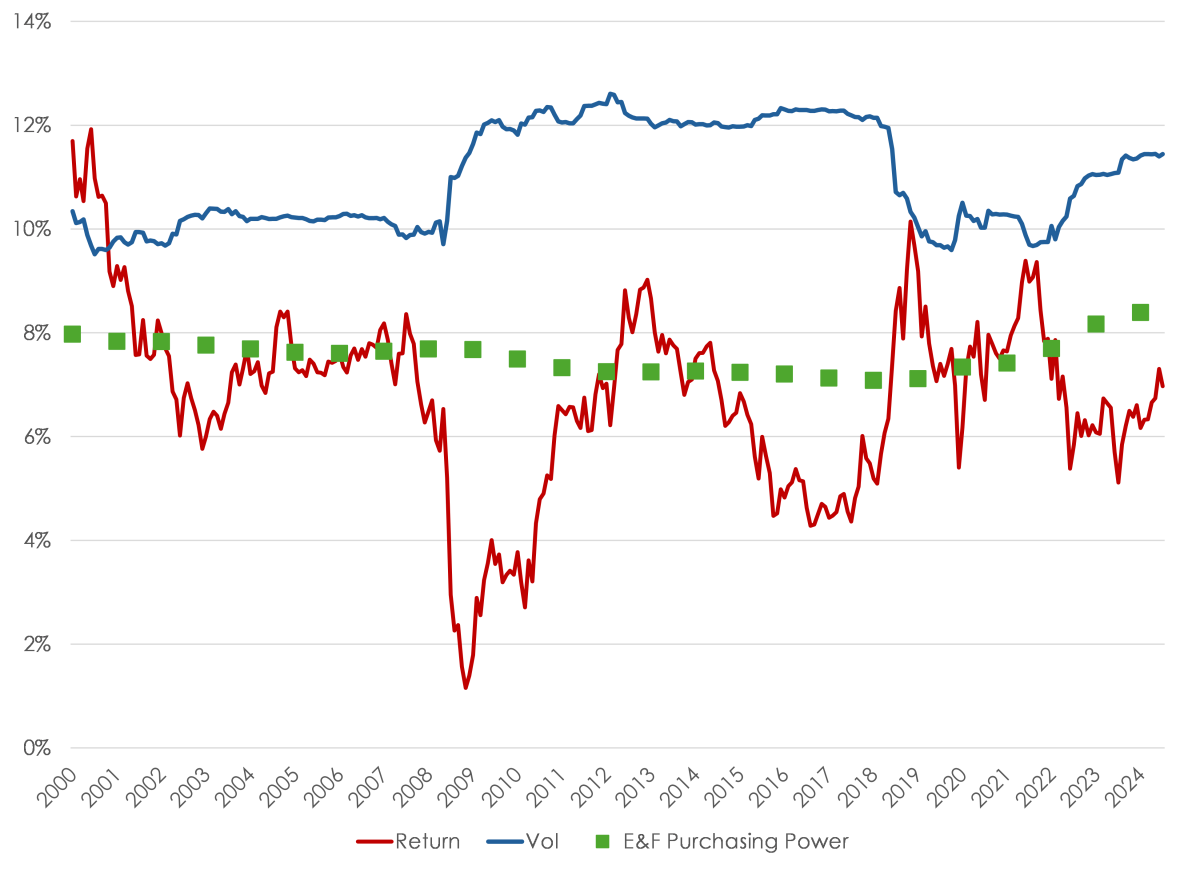

As it turns out, over the long term, it is actually more likely for a portfolio to meet a market-based risk objective than to meet a market-based return objective. The following chart shows the rolling 10-year returns and rolling 10-year volatility of a 70/30[1] portfolio with annual rebalancing. An immediate observation is the general stability of volatility over the long term compared to the wide range of outcomes for 10-year returns. Generally, volatility ranged between 10% and 12%, while returns ranged between 1% and 10%.

While investment teams create diversified portfolios that attempt to smooth the peaks and troughs of public markets, the reality is that stock and bond market beta are essential return drivers for portfolios[2]. In 2010, when the trailing 10-year return of a 70/30 portfolio was roughly 4% per year, there probably weren’t many investors sporting a 10-year return of 8% per year. The poor E&Fs with purchasing power return objectives didn’t have a chance (as shown by the green dots).

For the rare investment team that did generate an 8% 10-year annualized return through 2010, I can only imagine how much risk there was in that portfolio. Actually, I don’t think I want to know – that seems like a frighteningly high level. And frankly, as a board member, you would probably want to know. Even though the team generated an exceptional return, the conclusion may be that it was not worth the risk.

Rolling 10-year return and volatility of a 70/30 portfolio (w/ annual rebalancing)

As investment teams build portfolios, generate capital market expectations, calculate efficient frontiers, and select an asset allocation, the selection process often is based on return. Return expectations fluctuate over time, while many portfolio objectives stay relatively constant. Meaning, portfolios built to meet risk targets can experience meaningful change as return expectations rise and fall (i.e., think investment-grade bond allocations from 2009 to 2019, compared to the prior decade). Thus, as the portfolio composition changes in an effort to continue meeting the return target, what must change is the portfolio risk. When expected returns are low, portfolio risk must rise to meet the return objective; when expected returns are high, portfolio risk can decline.[3]

If a board has instituted a risk objective, this acknowledges that risk premia vacillate over time and there can be stretches where portfolios simply cannot meet high return hurdles without taking inappropriate risk. Similarly, in moments where risk premia provide enhanced compensation, why not take advantage of the fact that the portfolio can afford a level of risk that provides surplus compensation?

I appreciate that, by switching to a risk-based portfolio objective, a board relinquishes some control of return outcomes to the whims of the markets and may have to endure stretches where returns trail important hurdles (such as pension liabilities costs, or positive real returns). However, in selecting a risk-based portfolio objective, the board can also be more confident that the investment team is more likely to construct a portfolio that can adhere to the target, and likely optimize the return given the risk objective. Further, the board can have greater confidence that the portfolio is not making wild swings in low return environments, or unnecessarily pulling back in high return environments.

Think About It

I don’t expect institutions to suddenly change their portfolio objectives to risk-based objectives based on this blog post. But I would encourage investors to think about it and let it percolate. I get it, the idea may seem a bit radical, impractical, idealistic, and so on. It took me a year to fully get on board, but keep in mind, I didn’t come up with the idea. Some of the largest, most sophisticated and forward-thinking institutional investors did. That should give you something to think about.

About the Contributor

Steve Novakovic, CAIA, CFA is Managing Director of Educational Programming for CAIA Association. He joined CAIA in 2022 and has been a Charterholder since 2011. Prior to CAIA Association, Steve was a faculty member at Ithaca College, where he taught a variety of finance courses. Steve started his career at his alma mater, Cornell University, (B.S. 2004, MPS 2006) in the Office of University Investments. In his time there, he invested across a variety of asset classes for the $6 billion endowment, generating substantial insight into endowment management and fund investing across the investment landscape.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/

[1] 70% MSCI All-Country World Index USD Gross Return, 30% Bloomberg Global Aggregate USD Total Return

[2] A brief aside, I would like to make a point to all the folks who get up in arms about volatility smoothing for illiquid assets. Over the long term, does it really matter? Look at the chart, a 70/30 portfolio exhibits quite stable levels of volatility. It took an event like the great financial crisis to cause a “spike” in 10-year volatility from ~10% to ~12%. After the GFC finally rolled off, vol fell back down to ~10%. COVID pushed vol back up, but not to the level generated by the GFC. I fail to see the big deal that year over year, the reported volatility of certain illiquid investments may not fully represent “true” risk. Over the long run, the vol will smooth out, just like with the 70/30. Also, there are far better and more relevant measures for “true” risk we can use for illiquids, such as max drawdown, skewness, or maximum permanent loss.

[3] A brief aside on risk parity versus risk-based benchmarks. Risk parity, as defined in the CAIA curriculum, is an asset allocation approach that generates allocates based on balancing the contribution of each asset to portfolio risk. In other words, each asset class contributes an equal amount of risk to the portfolio. With a risk-based benchmark, the individual asset class weightings are not pre-determined. Rather, the final asset allocation should generate a portfolio with an expected risk equivalent to the expected risk of the benchmark.