By Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CFP®, CIPM, FDP, Managing Director, Content & Community Strategy, CAIA Association

Direct lending came of age in a period of low rates, low inflation, (late-stage) globalization, and easy monetary policy – all wrapped with a supportive regulatory environment that shifted supply from banks to investors. While direct lending is not the only sub-strategy of the private credit complex, it has been the one that’s catapulted the asset class into the mainstream and been the beneficiary of broad-based product development. However, with few exceptions around the world, those same underlying market backdrops that coincided with its growth have changed or are in flux – so what is private credit’s new value proposition today and, importantly, how does the industry’s rapid growth impact global economies on a systemic level?

Yield Signs Ahead: The Backdrop of Macro and Allocations

Early investors in private credit treated the asset class (particularly direct lending) as a stable income engine: floating rates with consistent yields, low(er) volatility, and safety in seniority of company capital structures.

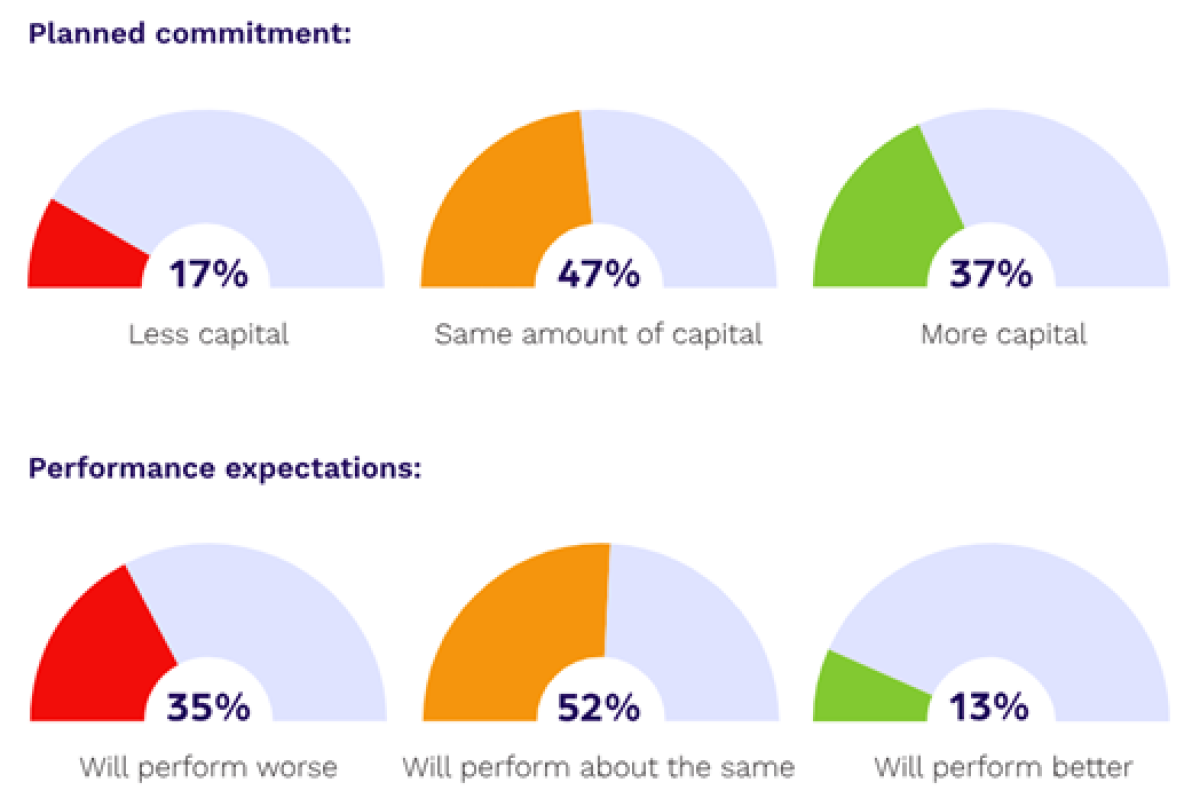

Is this sentiment beginning to change? Or are we heading towards a reallocation within the asset class? According to Preqin’s asset allocation study earlier this year, although most institutional investors were maintaining or increasing their capital commitments, their expectations have diminished. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Private credit’s star begins to dim according to Preqin

Source: Preqin 2025 Asset Allocation Study

Beneath the headline fundraising numbers sits a more complex reality shaped by geopolitics, inflation, fractured supply chains, war, regulatory uncertainty and a credit cycle that still has not tested managers in a meaningful way (according to a recent LP conversation at SuperReturn, “2020 doesn’t count.”)

These macro forces are pushing investors to revisit underwriting assumptions that may have seemed safe even two or three years ago. In some of our conversations around the world, credit professionals are making it clear that the macro backdrop is no longer a passive input like it was during the previous decade…in fact, it’s a driving part of the story.

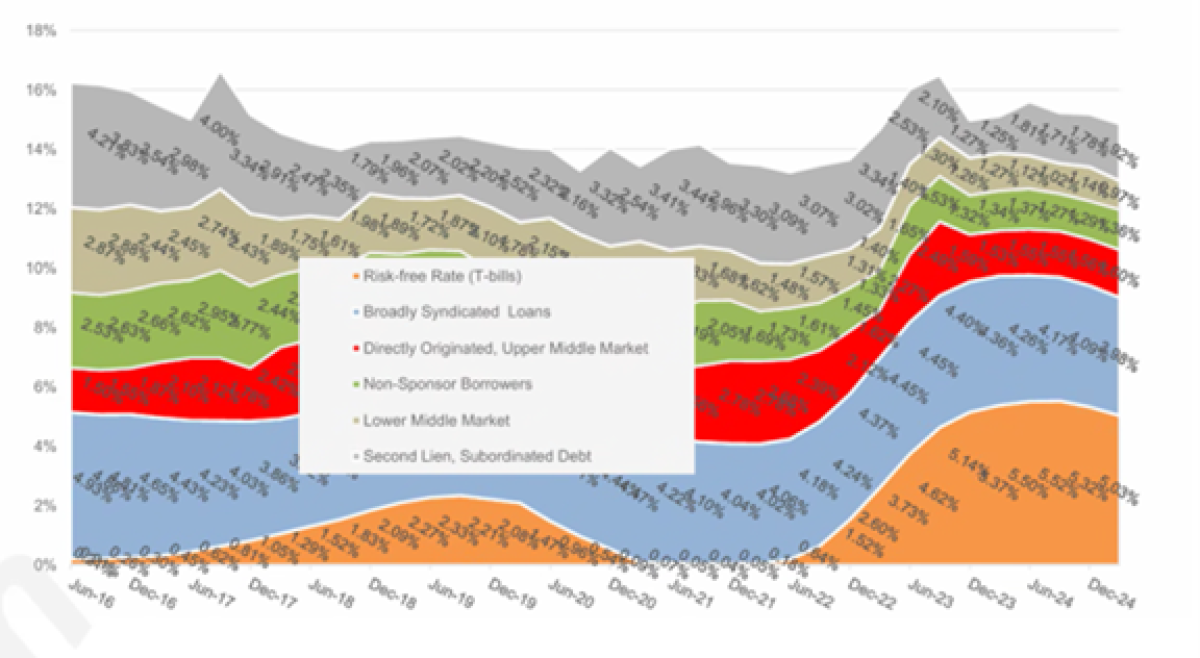

Inflation is the clearest example. Already outstanding senior secured loans benefited enormously from floating-rate structures when the rate regime shifted from zero to…not zero. Rising base rates boosted cash yields overnight, which was very positive for the asset class at face value. However, it’s worth noting that higher base rates have simply led to spread compression, as shown in Figure_.

Figure 2: Private Credit Spreads

Source: Cliffwater

Perhaps we’re entering into the testing period of outstanding vs. new issuance. If you go back to your Finance 101 days, think about inflation’s impact on the financial statements. We’re now in a period where we may be testing the limits of interest-coverage assumptions – according to a WithIntelligence article, interest rate coverage ratios have fallen from 3x to 1.5x from 2020 to 2025.[1] Borrowers whose cost structures are also feeling inflation can pass along only so much to consumers, so you have challenges on the top and bottom end of a traditional income statement .

Geopolitics amplifies this uncertainty. War in Europe, supply chain bifurcation with China, and the potential for sudden and erratic policy shifts in Washington all feed into underwriting credit risk, now at a local and a global level. In some of our conversations, some investors noted that allocating to the US used to feel like a “safe haven,” but that policy unpredictability is now something they need to model directly. In other words, while the U.S. may still be the safe haven (and the largest percentage of private credit), perhaps it's the cleanest dirty shirt in the laundry pile.

This is leading many allocators to widen the dispersion in their underwriting frameworks. Instead of a single central case with mild stress testing around it, they are modeling broader, more volatile paths: inflation surprise scenarios, regulatory shifts, prolonged supply-chain disruptions and region-specific downturns. That is a fundamentally different mindset from the last decade.

A Reality (Credit??) Check on Direct Lending, Commoditization, and Competition

Scale has been a strength of private credit’s ascent, driven by some of the largest GPs with strong capabilities to come to market quickly and capture investor capital, but it also brings new forms of risk. As I mentioned before, the private loan market has not truly lived through a deep, prolonged credit downturn while it has been this large. And with more capital chasing similar deals, the direct-lending market has become more commoditized, which can lead to cutting corners for newcomers needing to compete.

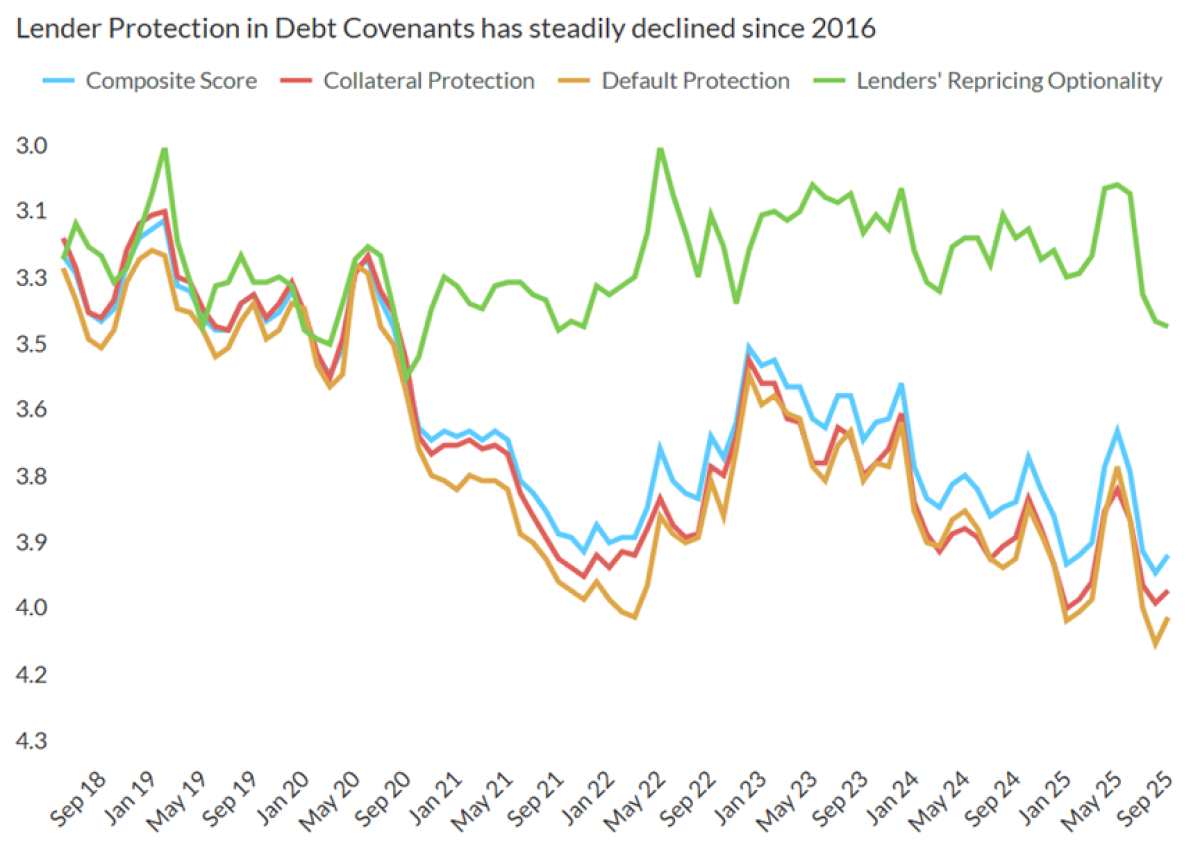

Figure 3: Covenant Review’s Documentation Score (Fitch)

Source: Fitch Ratings, “U.S. Leveraged Loan Finance Shows No Classic Bubble Signs”

That competition shows up first in underwriting: thinner covenants (as shown in Figure 2), higher leverage, and more “creative” loan structures (more PIK anyone?). It also shows up in the media. When private credit was small, borrower issues rarely made the front page. However, as funds get larger and borrowers become higher profile, there’s less room for error.

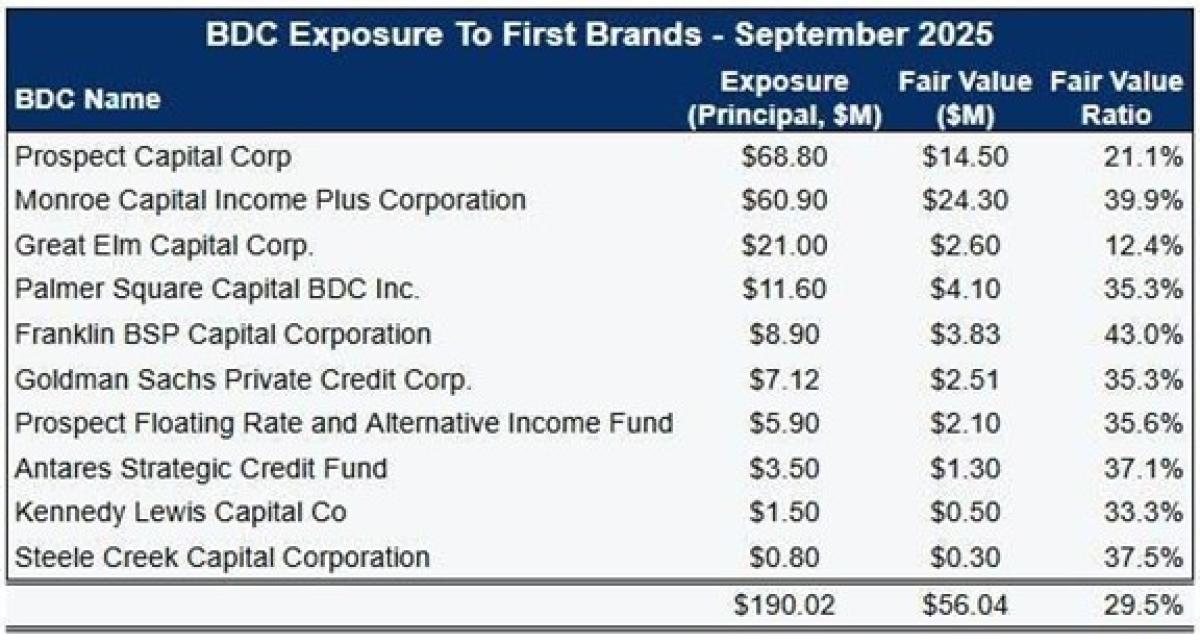

The First Brands Group bankruptcy is a textbook case. The auto-parts supplier collapsed with more than $10 billion in liabilities, and the coverage was swift. Courts ordered an independent probe into allegations of fraud[2] and several BDCs marked loans down to a fraction of their principal (shown in Figure 3).[3] The question the media is asking: are these isolated incidents, or signs of a broader underwriting problem? Some argued that it was simply idiosyncratic and not an indication of broader stress in the system. Others pointed to it as evidence that private credit’s due diligence discipline must evolve as financing structures become more complex.

Figure 4: Fair Value to Principal for First Brands in BDCs

Source: 9fin

I bring this up because, just like hedge funds, crypto, and non-traded REITs, one or two bad headlines can set the entire industry back and dampen confidence and investor trust. While early indications show that First Brands was an isolated incident, many GPs underscored the importance of comprehensive underwriting, covenants, and due diligence, while many LPs have shared that they worry about some of the more “creative” things they see in fund offerings. At a meta level, First Brands shows what happens when a much larger private credit ecosystem experiences the kind of messy borrower outcome once confined to footnotes. This is the natural byproduct of scale: the bigger the market gets, the more likely isolated credit failures will be highly visible… and highly scrutinized.

Collateral Damage vs. Collateral Opportunity: Distressed and ABL

As direct lending becomes more crowded, many LPs are looking for differentiation and many GPs are pushing into areas that will present LPs with differentiated products. As we have shared before (here and here), asset-based lending (ABL) has gone full circle from the early 2000s: being a (boring?) lender of last resort within banks to a (shiny) primary strategic focus for many asset managers.

Unlike direct lending, ABL tends to provide downside protection through the potential for higher recovery rates, introduce idiosyncratic risk via specific collateral, and diversify the rest of the portfolio from more traditional buyout cycles. In many cases, GPs see a path to differentiate themselves by financing receivables, inventory, equipment, IP, royalty streams, subscription contracts, or even fund NAV (which deserves its own article). Side note: one panelist of mine recently said that hard asset ABLs may be more attractive vs. intangible balance sheet assets (receivables) in a period like I mentioned regarding geopolitical instability.

For investors, when macro volatility rises, structures where collateral can be monitored, valued, and seized if necessary present an attractive value proposition. At the same time, ABL introduces new due diligence challenges. Collateral-driven strategies require deeper diligence, expertise, surveillance systems, and more precise recovery modeling. This isn't something that your every-day direct lender can do, nor are the same underwriting skillsets as easily transferable for LPs trying to invest with these kinds of GPs.

Along the same theme of what’s old is new again, there have been several recent conversations around the growing opportunities in the distressed market. Not very uplifting but the best defense is sometimes to play offense, right?

Fitch recently announced that the leveraged loan market default rate rose to 5.0% over a trailing 12-month period, the highest it has been since 2008, and are forecasting loan default rates at 5.5% for the entire year.[4] While leveraged loans serve as a proxy, private credit markets may begin showing similar signs of strain, which may lead to more refinancing and restructuring transactions. Against this backdrop, major firms[5] have highlighted an active pipeline in distressed and opportunistic credit, citing corporate stress linked to higher financing costs and uneven earnings.

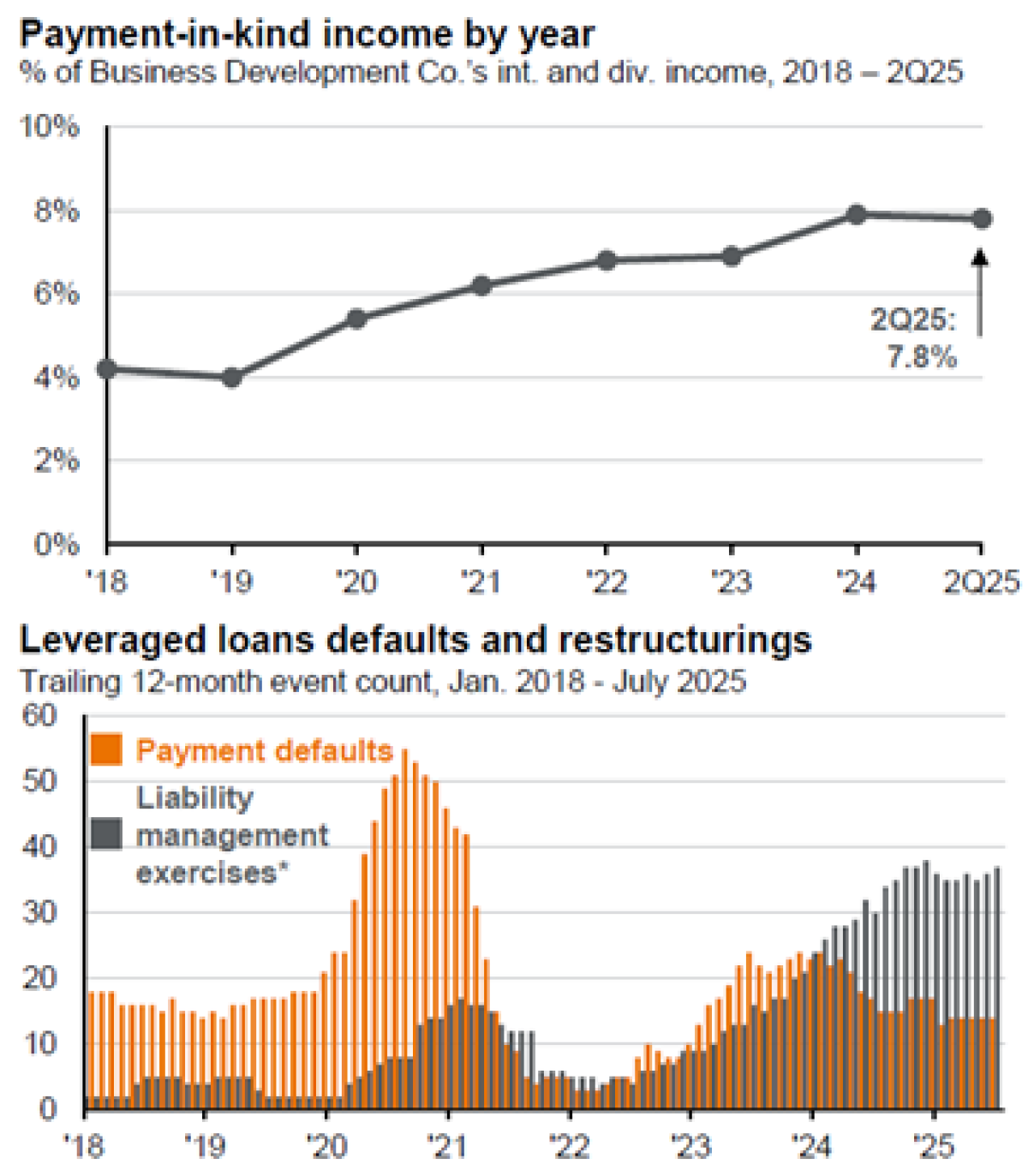

Figure _ shows two great charts from JP Morgan that help look under the surface beyond default rates as we think of them. First, PIK % is up, almost 2x from pre-COVID and second, restructurings are massively up. In other words, to avoid a (technical) default, the lender will agree to restructure terms to ensure the loan remains performing. This can be okay if the company is able to turn things around before maturity, but it is really kicking the can down the road in the simplest sense. It’s also worth noting that these mechanisms have increasingly been included as an option for borrowers upon origination.

Figure 5: PIK and Restructurings

Source: JPMorgan Guide to Alternatives

To Big To Fail 2.0? Do You Even Loan, Bro?

There is an excellent and nerdy piece by Chris Schelling, CAIA, that I would encourage you to read on the subject of the market’s size and systemic credit risk. As I have mentioned before, the TAM of the credit markets is much larger than the AUM in this space. Another interesting perspective I heard from an investor was that the shift from banks to private investors means that systemic risks will lead to losses being less socialized amongst taxpayers (like when banks were bailed out in the GFC). I don’t know if that’s necessarily true, as many of these asset owners (insurance companies, pensions, etc.) are just as important to our broader society, but it does spread the risk around a bit more than concentrating it with the big banks.

All that said, many investors believe private credit is now large enough, interconnected enough and widely held enough that stresses in one corner can propagate through the system. Whether that’s true remains to be seen, given private credit is still small relative to broader credit markets. However, it may mean that as public and private markets converge, price discovery will become inevitable and investors will need to be educated on appraisal-based valuations vs. market pricing mechanisms. Blue Owl's decision to call off the merger of its publicly traded BDC and its non-traded credit fund suggests investors may be catching on to those differences, despite some pundits claiming that mark-to-market adjustments equate to realized losses.

In this case, it was simply bad timing. Like publicly-traded REITs, publicly-traded BDCs prices and NAVS eventually converge. The desire to merge platforms, scale vehicles and serve both public and private channels is real, but liquidity and valuation profiles must line up. When they don’t, the market forces a rethink.

Putting It All Together

When you step back, the narrative is not bearish or bullish on private credit. Instead, it’s more opportunistic and nuanced. The cyclical factors today (inflation, geopolitics, tighter financial conditions, and isolated borrower blowups) make private credit more complicated. But the long-term forces maintain a powerful backdrop to its growth. Bank disintermediation, demand for yield, growth in private markets, and the expansion of collateral-based strategies all support the asset class’s longer-term growth. Not to mention the fact that private credit still offers a yield premium to public markets.

Private credit can still be a compelling long-term tool for portfolio construction. It just isn’t the easy beta exposure it might have looked like during the era of falling rates and quiet geopolitics. This next chapter will reward those who understand where to pick their spots .

About the Contributor

Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CFP®, CIPM, FDP is Managing Director, Content & Community Strategy at CAIA Association. His industry experience lies in private wealth management, where he was responsible for asset allocation, portfolio construction, and manager research efforts for high-net-worth individuals. He earned a BS with distinction in finance and a master of finance from Pennsylvania State University.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/