Herbalife filed an 8-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission July 29th, including a press release dated the day before. The company reported quarterly revenue of $1.31 billion, and a second quarter EPS of $1.55. This missed expectations. Polled analysts had expected revenue of $1.36 billion, and $1.56 a share.

Herbalife filed an 8-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission July 29th, including a press release dated the day before. The company reported quarterly revenue of $1.31 billion, and a second quarter EPS of $1.55. This missed expectations. Polled analysts had expected revenue of $1.36 billion, and $1.56 a share.

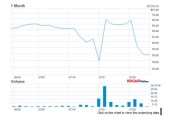

The stock price chart shown here (copied and pasted from Nasdaq.com with gratitude) represents the one month in the life of Herbalife’s stock price (NYSE: HLF) that culminated with this announcement and the resulting dip. Note there are twin dips. The stock price had already tested the $54 price level a week before. The timing of that first dip isn’t especially mysterious. On Monday, July 21, Ackman told the cable network CNBC that he would be giving a presentation of Herbalife. Ackman talked tough; as Ackman can – he said he would expose the “incredible fraud” that was is Herbalife. The stock lost 11% of its value that day.

After Ackman did give that presentation on the 22d, though, Mr. Market seemed to conclude that Ackman didn’t have the goods, and the price returned to roughly the neighborhood it had occupied before the CNBC appearance.

Whether this second dip will prove more lasting is another matter. This came about because Herbalife has just missed expectations for the first time since 2008.

Now I know that a lot may be said about the arbitrariness of the expectations game. But I’m not going to bother saying it, because Herbalife is playing a game of a different sort right now, the game of “outlast the high-profile short.” And I’m checking in on that one.

Is it too little, too late for Ackman?

For today’s lesson, let’s start with the basics, and then proceed to some history. Anyone already sufficiently familiar with both may be excused.

Ackman’s case is that Herbalife’s business model is a pyramid scheme. He seems to hope for enforcement action against it, and that would certainly undermine its price and gladden short sellers. But in an alternative scenario, the pyramid scheme (if it is one) might collapse on its own weight, the way they usually do in time. Pyramids are inherently unsustainable on any planet with a limited number of suckers (and, though the number of suckers on our home planet is sadly large, it is in principle finite).

Suppose I send you a note, “Dear AllAboutAlpha reader. Please send me $5. Also, send a letter like this one to five of your friends, asking them to do the same. You will receive $25 for your $5 and we’ll both be happy.”

Suppose I keep it as simple as that. Would it make a lot of sense for you to send me the $5? No. Most people understand this – certainly anyone sophisticated enough to be reading AllAboutAlpha would tell me upon receipt of that missive that I ought to head to Hades. I won’t further detail that point here.

Multi-Level Marketing

The prohibition of pyramid schemes does not amount to a prohibition of all multi-level marketing (MLM).

Tupperware, for example, lawfully sells storage and serving products branded with its name and the well-known “burp” on the one hand. It also lawfully offers to some individuals the right to offer its products to other potential customers in return for initial entry costs (in effect, purchasing a Tupperware franchise) on the other. That much is uncontroversial. Nor is the sale of a Tupperware franchise a security requiring registration as such.

Where controversy begins to enter the picture is where distributors are compensated more for their recruiting than for the sales of the product, or where the two features of the situation are hopelessly intermingled. That happens readily as the distributors learn that the ‘real money’ is to be found in the ‘downstream’ profits: and of course those downstream are pressured into creating a further-downstream source of their profits in turn.

A key legal precedent in the area came from the U.S. Court of Appeals, 5th Circuit, SEC v. Koscot, (1974).

The distinction between Tupperware and Koscot is a tricky one, a matter it seems of degree. Note the following points: the fact that an actual product is involved does not save Tupperware from the charge that it is a pyramid scheme. Koscot, too, sold products: ‘Kosmetics.’ Also, the fact that there is a financial incentive for recruitment is not by itself forbidden. What is forbidden is fraud, such as a chain letter that merely pretends to be the sale of a product, when in fact the ’sale’ aspect of the situation could not possibly constitute a sustainable business plan.

Even constitutional law seems to have conspired to make all of this tricky, because advertisements for a “Tupperware Party” were central to an important first amendment case, and were found to be protected by that amendment. The case is SUNY v. Fox (1989).

As a very rough rule of thumb: if distributors can receive a rational return on their efforts (not a get-rich-quick type of return, just one that would justify a rational person in signing up) without recruiting other distributors, if the benefits of recruitment are a sort of bonus on top of that rational return., then the company will probably pass muster as a legitimate MLM.

This brings us back to Herbalife and Ackman’s bet.