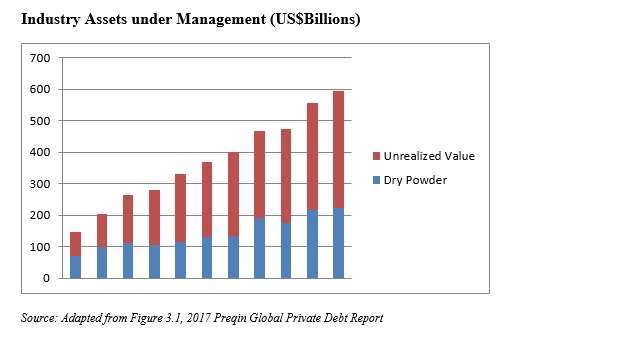

Preqin has issued a new report on global private debt. It begins with the observation that assets under management in the private debt industry (defined as the uncalled capital commitments plus the unrealized value of portfolio assets) have quadrupled in the last ten years, reaching $595 billion as of the end of the second quarter 2016.

Each of the last ten years has witnessed growth. Notably even the period 2008-09 saw expansion, not contraction, for this industry.

In the first half of 2016 alone AUM grew 7.1%. Preqin credits “strong fundraising, increased deal activity and investment performance” for this continuous expansion.

Breaking it Down

The two components of AUM mentioned above have told somewhat different stories over the last decade, though, Dry powder AUM (uncalled capital commitment) has had down years as well as up. It was down from 2008 to ’09, and down again from 2013 to ’14. But unrealized value has moved steadily skyward.

The expansion is not uniform when the industry is broken down by vintage year. Nearly three quarters of the dry powder (specifically 74%) is held in funds of quite recent vintage, 2014, 2015, or 2016.

Breaking funds down in another way, by strategy employed, Preqin tells us that distressed debt commitments to funds closed in 2016 grew 14% over those that closed in 2015, reaching $32 billion. That figure includes 18 such funds.

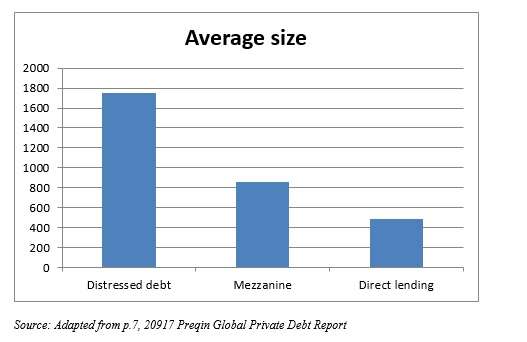

The size of the average distressed debt fund increased 46% from vintage 2015 to vintage 2016. The average size of such funds of the latter vintage is contrasted below with the average size of mezzanine and direct lending funds. See the graph below.

In all, 2016 was a banner year for distressed debt private debt funds: they haven’t had as large a harvest of funds raised since 2008. Preqin cautions, though: “[F]und managers may face challenges in securing capital in 2017 as investors view distressed debt less favorably than both direct lending and mezzanine.”

Greater Concentration

The broad trend is toward greater concentration of capital among fewer funds. The largest ten funds to close in 2016 accounted for 47% of the overall funds raised.

Furthermore (and this returns us to an earlier point, the credit Preqin gives the fundraisers themselves for expansion, as well as to the fact that patience is a fundraising virtue): the funds that did close in 2016 had quite generally been successful in reaching their own original fundraising targets, even though they took longer to reach a final close than in past years.

The average time spent “on the road” for a fund of vintage 2016 was 21 months, a record for that particular statistic. The previous record holder there was vintage 2012, when the closers have an average fundraising time of 19 months.

Who Are the Active Investors?

The report spends some time, too, on the evolution of the investor universe for debt funds.

Institutions continue to constitute the chief source of investment in this space (85% of it). Within the broad umbrella of “institutions,” the largest investors are: private sector pension funds, public sector funds, and foundations, in that order.

Happily, nearly two thirds (specifically 63%) of private debt investors interviewed said that they believe their interests are in alignment with those of the fund managers.

Investors generally understand that there is a trade-off, that if they stint on fees they may compromise portfolio performance, and as a consequence of this understanding they are “satisfied with compensating managers for incremental portfolio gains.”

They are also discriminating about the differences in the types of funds, and how those differences may impact incentive structures. For example: “Direct lending fund generally carry no equity component, which is one of many reasons they may be less costly for a manager to maintain. In this case, investors can expect to pay less in management fees, despite seeing returns that, on a risk-adjusted basis, can be quite attractive to them.”

Investors do think there is room for improvement in this matter of incentive alignment, though. Investors in the private debt funds, for example, like to see managers who eat their own cooking; they’d like to see greater transparency at the fund level; and they think hurdle rates can be improved.