By: CAIA CEO Bill Kelly.

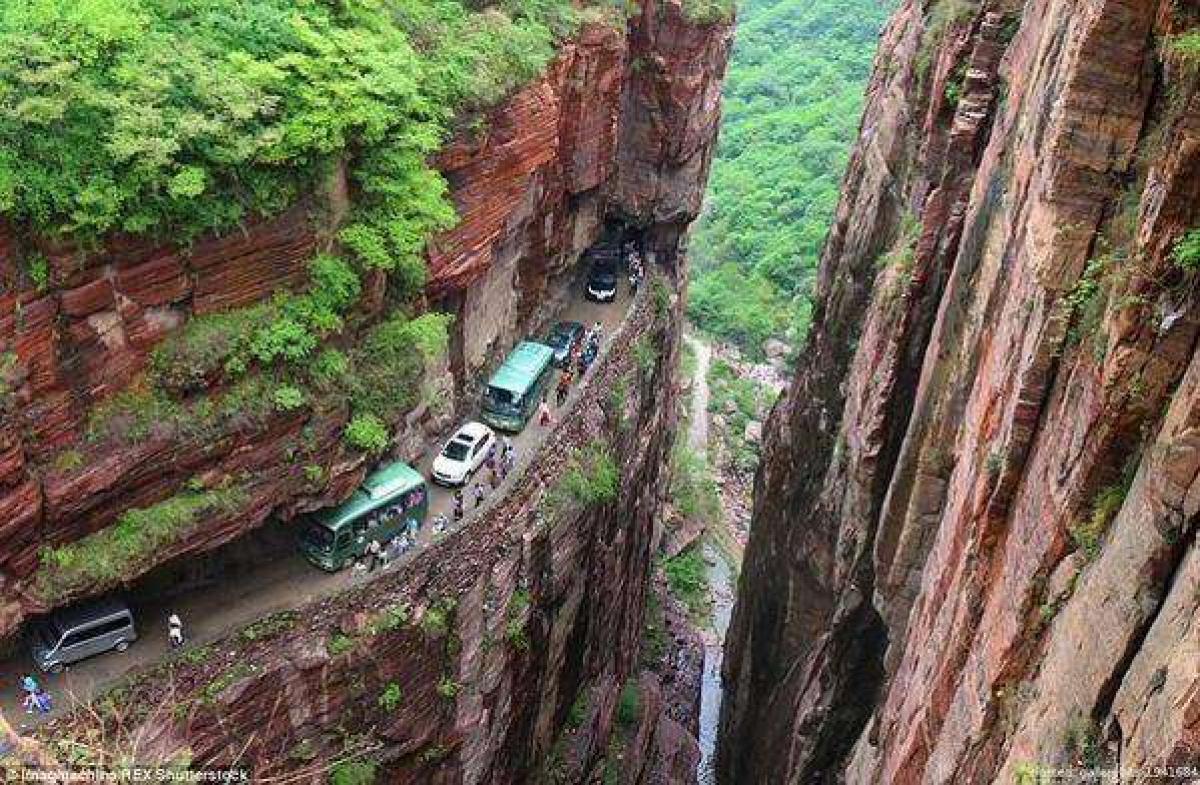

Dateline, Guoliang Tunnel Road in China. This stretch of highway is a perennial favorite in the annual ranking of the world’s most dangerous roadways. Surprisingly, it ceded the top spot in that category this year to the North Yungas Road in Bolivia, but some pictures are simply not suitable for publication in this family-friendly blog. The path from Point A to Point B is rarely a straight line and the obstacles encountered along the way are not always predictable or simple to navigate. The safest route is the marked roadway and with or without guardrails the danger of straying is real and potentially fatal.

For many of us, it is hard to imagine a byway with so few bounds. Guardrails, lights, painted lines, and signs keep us on track. Speed is often monitored to moderate the behavior of those more aggressive travelers, to further keep us safe within the marked boundaries that we all must share. Perhaps the world’s safety regulators should compare notes with those overseeing our financial markets.

The global financial markets are highly regulated and investor protection is almost always front and center, and that is a good thing. However, a hallmark of that safety-first approach is often accompanied by limitations of access to certain products and a call for a very porous guardrail system to allow unfettered exits, regardless of what might lurk on the other side. As our capital markets look to tack toward their own version of the Guoliang Tunnel Road, it might be time to contemplate the very best way to keep the financial traveler on that road, mostly because the terrain on the other side could be even more treacherous than the highway itself.

A recent article in CAIA’s Alternative Investment Analyst Review brings this point home in an elegant and statistically significant way. The author looked at the very best and worst performing days in the US equity markets over the last 50-some-odd years. Returns have almost always tended to cluster, in that some of the worst performing days were often followed by some of the best, and vice versa. The poster child for this thesis is the infamous Black Monday in October 1987 where the S&P 500 took back 20% of your capital and is far and away the largest recorded daily drawdown for that index. Absent guardrails, many investors jumped and locked in losses, as a plunge to the bottom of the ravine seemed inevitable. Much less reported is what happened the next day and the day after, where that same bottom-seeking index was up 5% and 9%, respectively. Not only would the investor seeking immediate “safety” have lost out on this bounce, but when would she deem it ultimately safe to come back in at all?

The very best value proposition for diversification is to provide the fortitude, or guardrails, to remain fully invested at all points of the market cycle. Tactical asset allocation is a dangerous off-road path and the old 60/40 allocation using just two asset classes will likely result in much higher correlations at this stage of the equity and fixed income markets.

If you are a thrill seeker with the unbridled discipline to have stayed in the equity markets over the ten-year period ended September 2017, you would have held one of the very best performing global portfolios, compounding your capital at an annual rate of 7.4%. You would also have withstood almost 16% annual volatility, and a "Guoliang Tunnel Road-esque" max drawdown of 46%. The introduction of a simple 20% alternatives allocation, coupled with 40% each to equities and fixed income, would have “cost” you about 130 BP’s of gross return per annum over that same ten years, but with 60% correspondingly lower levels of volatility and drawdown experience. Those sound like the type of guardrails that can keep more investors in the market with an ultimately safer glide path to retirement.

Seek diversification, education and know your risk tolerance. Investing is for the long term.