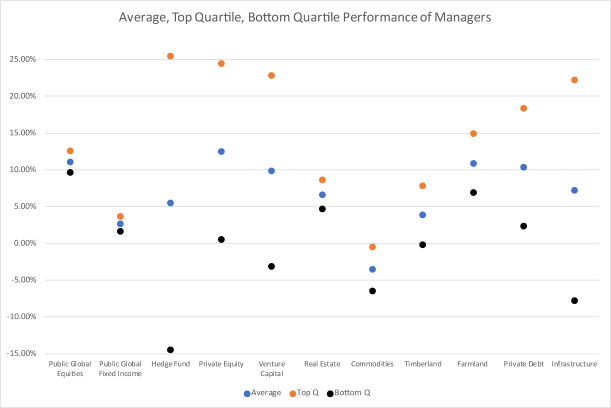

By Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM & Hossein Kazemi, PhD, CFA, CAIA Association & CISDM This is a summary of the editor’s letter originally published in the Volume 8, Issue 4 of the Alternative Investment Analyst Review, a journal published by CAIA Association. The Problem with Studies Many studies on allocating to alternative investments are flawed. They’re not necessarily wrong, they just ignore two very important characteristics: manager dispersion (or “manager selection risk”) and autocorrelation (i.e., “smoothing impact of risk estimates”). Whether it’s traditional or alternative investments, many of us often use index data when analyzing the risk and return characteristics of different asset classes. Even at CAIA Association, we do this - look no further than the list of different asset class returns, aptly named “The List,” we publish in our quarterly journal, Alternative Investment Analyst Review. Using index data isn’t inherently wrong, as it can answer a lot of questions and describe general characteristics of these asset classes. However, when we begin to think about actual portfolio application (that is, actually investing in a portfolio of third-party managers), index-level data doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story. While indexes serve as good proxies for traditional asset classes like publicly traded global stocks or fixed income, alternative asset class benchmarks are rarely investable and, in some cases, may not accurately represent the experience of an actual investor. This study seeks to mitigate the two key characteristics of manager dispersion and return smoothing, both of which are essentially ignored at the index level. Let’s take each issue one at a time. Issue #1: Manager Dispersion and the Impact on Index Sub-Manager Diversification  Exhibit 1: Average, Top Quartile, and Bottom Quartile Performance of Managers Sources: See Appendix Many alternative investment indices are constructed by aggregating managers within the same asset class and/or those following a similar investment strategy (e.g., core real estate or venture capital). However, not every manager in the index is doing the same thing, which means the performances of these managers are less perfectly positively correlated with each other. As a result, alternative indices will have much lower volatility than the average single manager because the less than perfect correlations amongst them create an additional level of diversification. Exhibit 1 displays the average, top-quartile, and bottom-quartile investment manager performance for various asset classes. There is significant dispersion, or manager selection risk, associated with allocating to alternative investments. Additionally, it’s obvious that the dispersion of performance is not uniform among various asset classes. Exhibit 2: Smoothed and Unsmoothed Volatility and Drawdown Figures

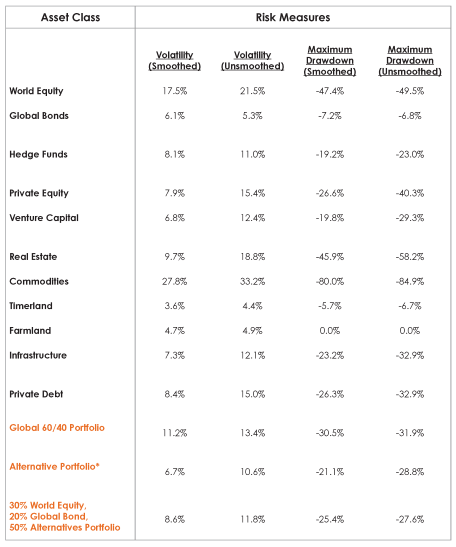

Exhibit 1: Average, Top Quartile, and Bottom Quartile Performance of Managers Sources: See Appendix Many alternative investment indices are constructed by aggregating managers within the same asset class and/or those following a similar investment strategy (e.g., core real estate or venture capital). However, not every manager in the index is doing the same thing, which means the performances of these managers are less perfectly positively correlated with each other. As a result, alternative indices will have much lower volatility than the average single manager because the less than perfect correlations amongst them create an additional level of diversification. Exhibit 1 displays the average, top-quartile, and bottom-quartile investment manager performance for various asset classes. There is significant dispersion, or manager selection risk, associated with allocating to alternative investments. Additionally, it’s obvious that the dispersion of performance is not uniform among various asset classes. Exhibit 2: Smoothed and Unsmoothed Volatility and Drawdown Figures  Unlike public markets, where pricing data is available daily, private markets and other alternative investment asset classes are usually appraised and reported quarterly. Less frequent appraisals can increase the likelihood of price smoothing. Additionally, quarterly appraisals are subject to an anchoring effect, meaning current appraisals are heavily influenced by the previous quarter’s appraisals. Over multiple quarters, recent prices become highly correlated to previous prices, which gives rise to autocorrelated return series. When autocorrelation is present in a series of prices, it can understate traditional risk metrics, such as standard deviation, maximum drawdowns, and correlation to other asset classes. If we simply look at raw returns, we find that most alternative investments exhibit a lower volatility than global equity markets, with some even lower than global fixed income markets. However, if we adjust for smoothing, we find these volatility measures increase, substantially in some cases. These figures are detailed in Exhibit 2. Notice that the volatility measures almost double for certain asset classes, namely private equity, venture capital, and private credit, when adjusted for smoothing. Without this adjustment, a portfolio manager seeking to maximize their risk-adjusted returns would likely overweight to these asset classes.

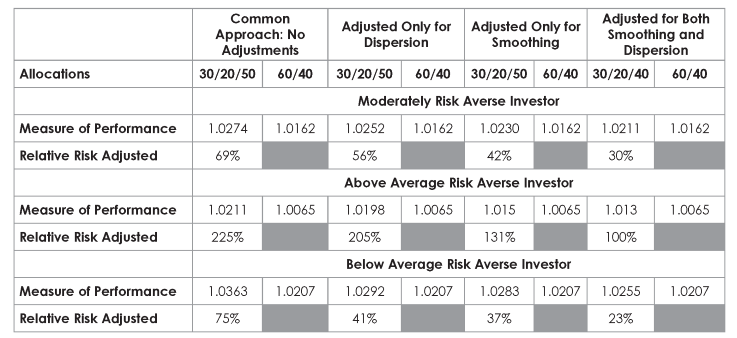

Unlike public markets, where pricing data is available daily, private markets and other alternative investment asset classes are usually appraised and reported quarterly. Less frequent appraisals can increase the likelihood of price smoothing. Additionally, quarterly appraisals are subject to an anchoring effect, meaning current appraisals are heavily influenced by the previous quarter’s appraisals. Over multiple quarters, recent prices become highly correlated to previous prices, which gives rise to autocorrelated return series. When autocorrelation is present in a series of prices, it can understate traditional risk metrics, such as standard deviation, maximum drawdowns, and correlation to other asset classes. If we simply look at raw returns, we find that most alternative investments exhibit a lower volatility than global equity markets, with some even lower than global fixed income markets. However, if we adjust for smoothing, we find these volatility measures increase, substantially in some cases. These figures are detailed in Exhibit 2. Notice that the volatility measures almost double for certain asset classes, namely private equity, venture capital, and private credit, when adjusted for smoothing. Without this adjustment, a portfolio manager seeking to maximize their risk-adjusted returns would likely overweight to these asset classes.  Summary of Findings While we do look at more traditional risk-adjusted metrics in the study, we decided to compare a traditional 60/40 global stock/bond portfolio to a 30/20/50 global stock/bond/alternative portfolio using the Morningstar’s Certainty Equivalent (CE) ratio for investors with below average, moderate, and above average risk aversions.[1] We first compare the CEs of both portfolios using a “Traditional Approach,” which simply looks at raw returns and standard deviations. As you might expect, the 30/20/50 portfolio is highly preferable to the 60/40 portfolio due to lower standard deviations and similar returns. We then compare the portfolios using an “Alternative Approach,” which adjusts the asset classes for autocorrelation, smoothing, and both combined. (We use a simulation approach and then employ the risk-adjusted performance measure used by Morningstar for ranking mutual funds to measure the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. We find that, although the 30/20/50 portfolio still returns a favorable CE, the benefits are reduced when these adjustments are made. These benefits decrease as the investor becomes less risk averse. Summary This study still supports the notion that alternative investments can benefit a diversified portfolio. However, it’s important not to overstate these benefits or ignore key characteristics that come with investing with alternative investment managers. The analysis presented here has three broad implications. The first, and more obvious, implication is that manager dispersion, or “manager selection risk,” reduces the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. On a positive note, even in the presence of manager selection risk does not decrease the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. These benefits are even more substantial for investors with above-average risk-aversion. The second implication is that we can measure the potential benefits of improved due diligence. For example, for average risk aversion, there is a 0.022% decline in the certainty equivalent when manager selection risk is considered. We can use this to measure to justify the amount that we should be willing to spend on due diligence to reduce manager selection risk. For instance, for each $100 million that we plan to allocate to alternative asset classes, we could spend up to $220,000 on manager due diligence and selection costs, not an insignificant amount. The third implication is that there are circumstances under which an asset allocator will be better off to invest in a fund of funds, reducing the manager dispersion risk of the portfolio. For example, an investor who plans to make a small allocation to a certain set of alternative asset classes would find it beneficial to select a fund of funds manager rather than assuming a significant amount of individual manager selection risk. Sources As mentioned in the text, the manager dispersion figures were obtained from various sources. The following is a list of sources and time periods covered by various strategies.

Summary of Findings While we do look at more traditional risk-adjusted metrics in the study, we decided to compare a traditional 60/40 global stock/bond portfolio to a 30/20/50 global stock/bond/alternative portfolio using the Morningstar’s Certainty Equivalent (CE) ratio for investors with below average, moderate, and above average risk aversions.[1] We first compare the CEs of both portfolios using a “Traditional Approach,” which simply looks at raw returns and standard deviations. As you might expect, the 30/20/50 portfolio is highly preferable to the 60/40 portfolio due to lower standard deviations and similar returns. We then compare the portfolios using an “Alternative Approach,” which adjusts the asset classes for autocorrelation, smoothing, and both combined. (We use a simulation approach and then employ the risk-adjusted performance measure used by Morningstar for ranking mutual funds to measure the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. We find that, although the 30/20/50 portfolio still returns a favorable CE, the benefits are reduced when these adjustments are made. These benefits decrease as the investor becomes less risk averse. Summary This study still supports the notion that alternative investments can benefit a diversified portfolio. However, it’s important not to overstate these benefits or ignore key characteristics that come with investing with alternative investment managers. The analysis presented here has three broad implications. The first, and more obvious, implication is that manager dispersion, or “manager selection risk,” reduces the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. On a positive note, even in the presence of manager selection risk does not decrease the benefits of allocating to alternative asset classes. These benefits are even more substantial for investors with above-average risk-aversion. The second implication is that we can measure the potential benefits of improved due diligence. For example, for average risk aversion, there is a 0.022% decline in the certainty equivalent when manager selection risk is considered. We can use this to measure to justify the amount that we should be willing to spend on due diligence to reduce manager selection risk. For instance, for each $100 million that we plan to allocate to alternative asset classes, we could spend up to $220,000 on manager due diligence and selection costs, not an insignificant amount. The third implication is that there are circumstances under which an asset allocator will be better off to invest in a fund of funds, reducing the manager dispersion risk of the portfolio. For example, an investor who plans to make a small allocation to a certain set of alternative asset classes would find it beneficial to select a fund of funds manager rather than assuming a significant amount of individual manager selection risk. Sources As mentioned in the text, the manager dispersion figures were obtained from various sources. The following is a list of sources and time periods covered by various strategies.

- “Guide to Alternatives, 3Q 2019,” JP Morgan Asset Management. This is used as a source of dispersion of global equity, global fixed income, US core and US non-core real estate, global private equity, US venture capital, and hedge fund managers. The time period covered is 1Q 2009-1Q 2019.

- Preqin Database. This is used as the source for infrastructure and private debt managers. In addition, we used this source to run additional checks on private equity, venture capital, and hedge fund managers. The time period covered is 1Q 2009-4Q 2018.

- CISDM Hedge Fund Database: This is used as a source to run an additional check on the dispersion of hedge fund managers. The time period covered is 1Q 2009-1Q 2019.

- “Insights into Efficiency and Manager Selection: A Look at Quartile Returns of Timberland Funds,” Chung-Hung Fu, Timberland, and Investment Resources, 2014. This is used as a source for timberland fund managers. The time period covered is Q2 2002-Q2 2014.

We did not have reliable sources for the dispersion of commodity and farmland managers. For commodity managers, we assumed they have the same cross-sectional dispersion relative to their means as that of the global equity fund managers. For farmland fund managers, we assumed they have the same cross-sectional dispersion relative to their means as that of the timberland fund managers. Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM is an Associate Director, Content Development at CAIA Association. Hossein Kazemi, PhD, CFA is a Senior Advisor at CAIA Association. [1] For an in-depth view of how a portfolio’s CE is calculated, simply follow the link to Morningstar’s rating methodology whitepaper and/or read the full article in AIAR.