By Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CIPM, FDP, Managing Director at CAIA Association

Takeaway: Alternatives are expected to produce half of industry revenue in a few years, despite representing just 12% of the $153 trillion global investable market in 2020, fueled by growth across strategies and a blurring of the lines between public and private capital.

When CAIA Association released its last major report, The Next Decade of Alternative Investments: From Adolescence to Responsible Citizenship, global public equity markets were in freefall as the COVID-19 global pandemic began its pillage through society. Since then, public equity markets have rebounded to new highs, public fixed income yields temporarily hit new lows, and private capital has continued to grow at an impressive pace.

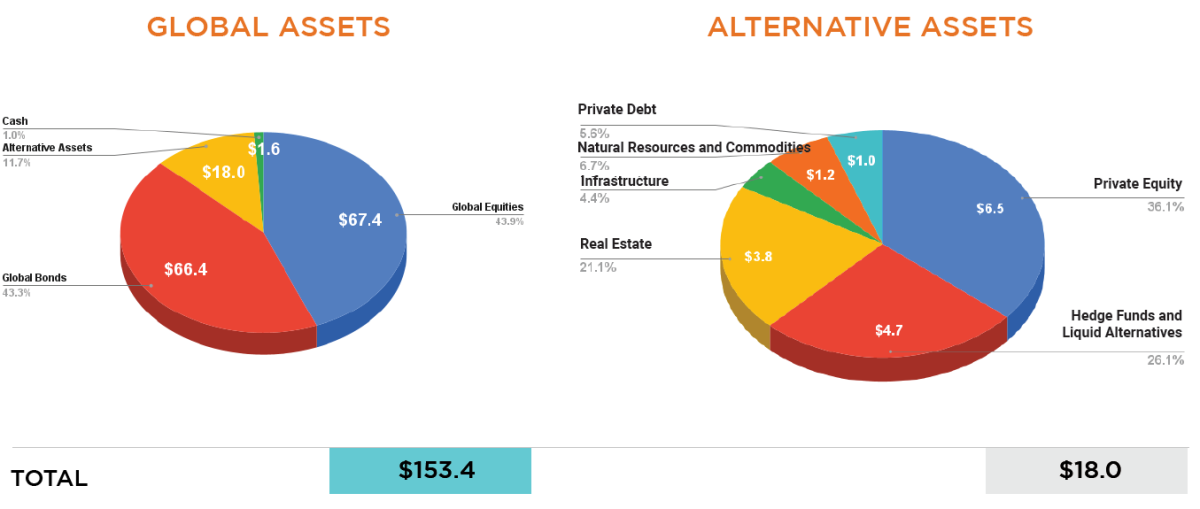

Source: “The Portfolio for the Future™” by CAIA Association

Exhibit 1 displays the global investible market between traditional and alternative assets.

As of the end of 2020, institutionally adopted alternative investments represented approximately $18 trillion in assets under management, or 12% of the $153 trillion market.[1]

Record low interest rates and muted forward-looking return expectations have caused asset owners to look for better sources of growth, income, and inflation protection. Fee compression in traditional markets and an evolution of capital formation toward the private corridors have simultaneously caused asset managers to diversify their revenue streams.

A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats…

Exhibit 2: Annualized Asset Class Performance, Risk, and Drawdowns

Source: Bloomberg, Burgiss, CAIA Association

The 2010s seem like a lost decade for investors in long-term diversified portfolios, when all you’ve needed is public equity and fixed income beta. Exhibit 2 displays the time-weighted returns, standard deviations, and maximum drawdowns as of December 31, 2020, using quarterly returns. Up until the global pandemic, the drawdowns of global public equity and fixed income markets were minimal. It really wasn’t until the equity market drawdown during early 2020 that investors rediscovered the benefits of diversification for the first time in many years.

…But the Waters Are Choppy

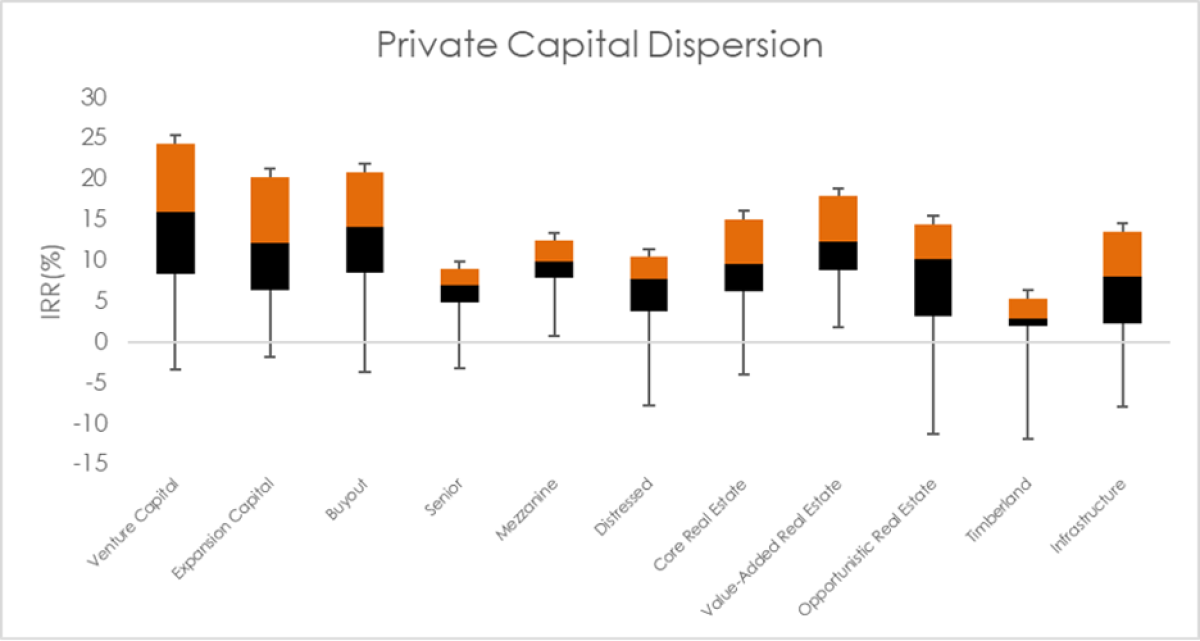

Exhibit 3: 10-Year Private Capital Fund Performance Dispersion

This box and whisker chart shows the performance differences amongst managers. From top to bottom, the chart identifies top 5%, top quartile, median, bottom quartile, and bottom 5%.

Source: CAIA Association, Burgiss. IRR data as of December 31, 2020

Unfortunately, aggregated private capital fund performance data remains misleading and doesn’t provide a look into what an average investor might experience with a top, bottom, or average performing fund manager, as shown in Exhibit 3. The skill required to select good managers is just as, if not more, important as having access to them in the first place. While the underlying risk exposures may be familiar to a public market participant (growth, income, and inflation protection), illiquidity and manager risk will drive much of the outcome.

Private Capital: Formation, Innovation, and Value Creation

The role of private equity in a company’s growth trajectory has evolved over time, starting with the funding model in the early stages. In 2010, the median venture-backed portfolio company could expect a single funding round before exiting as a public company through an initial public offering (IPO). That same median company could expect three funding rounds a decade later, supported by even larger commitments.[2]

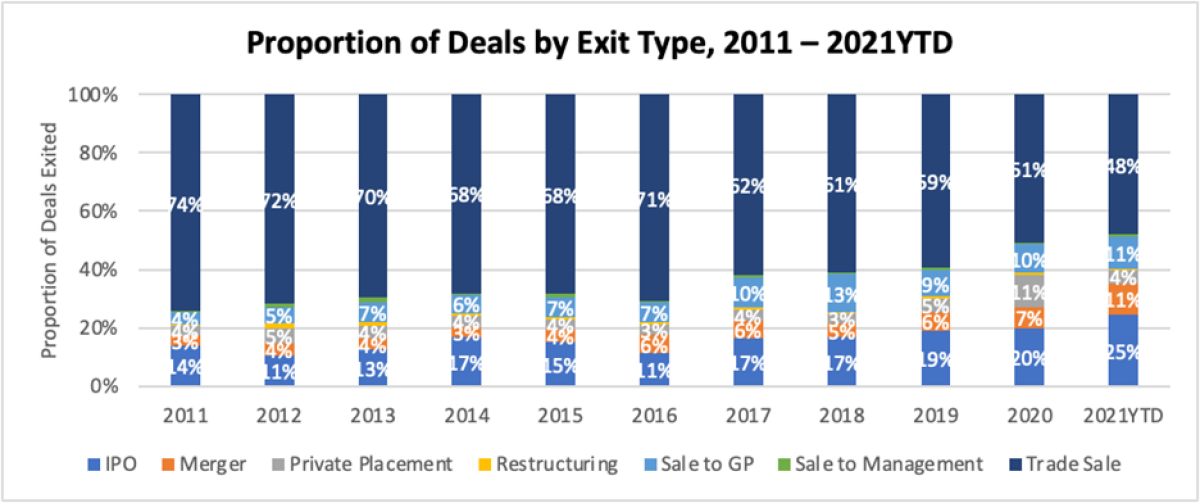

Private funding no longer just operates as a springboard for value creation; it’s become a viable permanent strategy. In fact, for many years, the majority of venture-backed companies have opted to stay private through a strategic sale or merger, rather than venture into the public markets, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4: Proportion of Deals by Exit Type

Source: Preqin

Portfolio companies have altered their preferences by favoring private markets to public, and public market investors have tried to access private equity in any way possible. In 2020, 276 special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), corporations tasked explicitly with investing in privately owned companies, went public through initial public offerings (IPOs). For reference, that number equals the total number of SPAC IPOs from 2011-2019 combined.[3] SPACs, like private equity funds, provide opportunities for outperformance but still deliver a wide dispersion of outcomes, especially when comparing those that are operator- vs. investor-led.

Private Credit: Thirsty for Income on a No-Liquids Diet

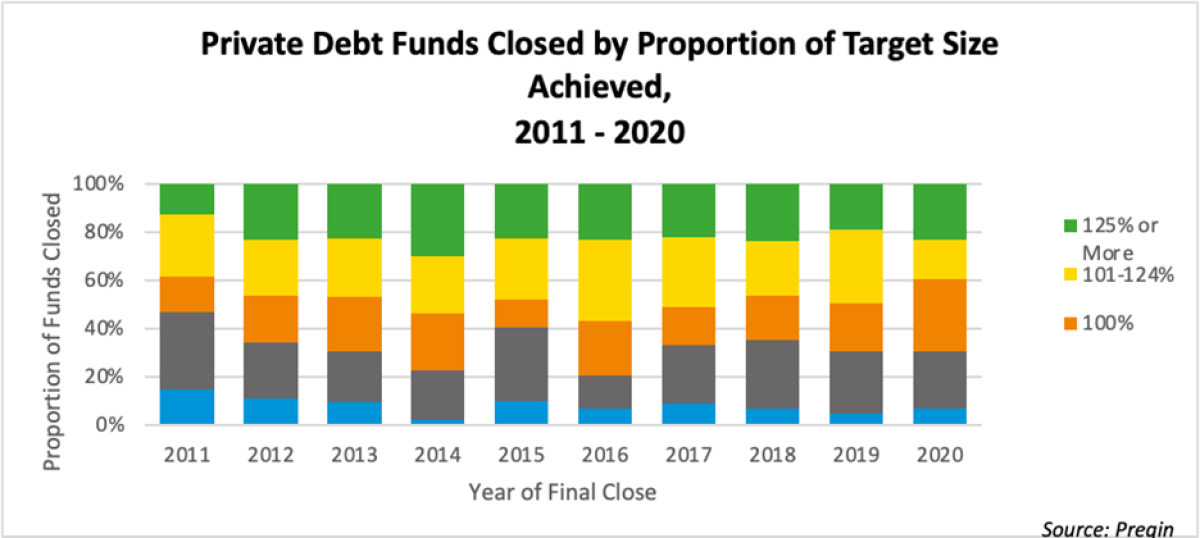

Exhibit 5: Private Debt Funds Closed by Proportion of Target Size Achieved

Source: Preqin

In 2020, private credit funds reached the $1 trillion milestone in assets under management, a twenty-fold increase over the previous two decades. An asset class that once served as an opportunistic, aggressive, or speculative satellite for diversified investors has now become a core piece of a sophisticated asset allocation. As assets have poured into these funds, the composition of strategies has evolved, with massive fundraising efforts in Direct Lending strategies. In fact, direct lending now represents more than half of fundraising in 2021.[4]

Such strong demand for income, public or private, has caused many issuers to relax their covenants, something we highlighted in The Next Decade. In 2021, over 90% of loan issuance was considered covenant-lite, a new record. For comparison, a little over 20% of loans issued in 2007 were considered covenant-lite. [5] While the risk of default translates to more volatile pricing in public credit, it doesn’t always translate to private credit funds. At first glance, an uninformed investor might think that private credit has historically experienced drawdowns like those of investment grade corporates, when the underlying credit risk of these loans is far greater.

Real Assets: Location, Inflation, and Transportation

Despite all the disruptions caused by the global pandemic, real estate value continued to grow in aggregate. According to MSCI, the total value of real estate held for investment (equity and debt) reached a new milestone of $10.5 trillion in 2020.[6] However, we believe real estate must overcome three cyclical and secular trends:

1. A rotation away from brick-and-mortar retail toward industrial and logistics due to e-commerce trends

2. The reimagination of office space, as more companies offer remote work options for employees

3. A renewed focus on sustainability, as new and existing properties weigh physical and transition climate risks.

In 2016, Oxford Economics estimated global infrastructure investment needs to be approximately $94 trillion by 2040,[7] driven both by needs to update existing and aged infrastructure projects and to invest in new, more sustainable ones. For most governments worldwide, infrastructure needs far outweigh the resources available through taxation and other fiscal policy,[8] suggesting a renewed call for private capital to fill the gap.

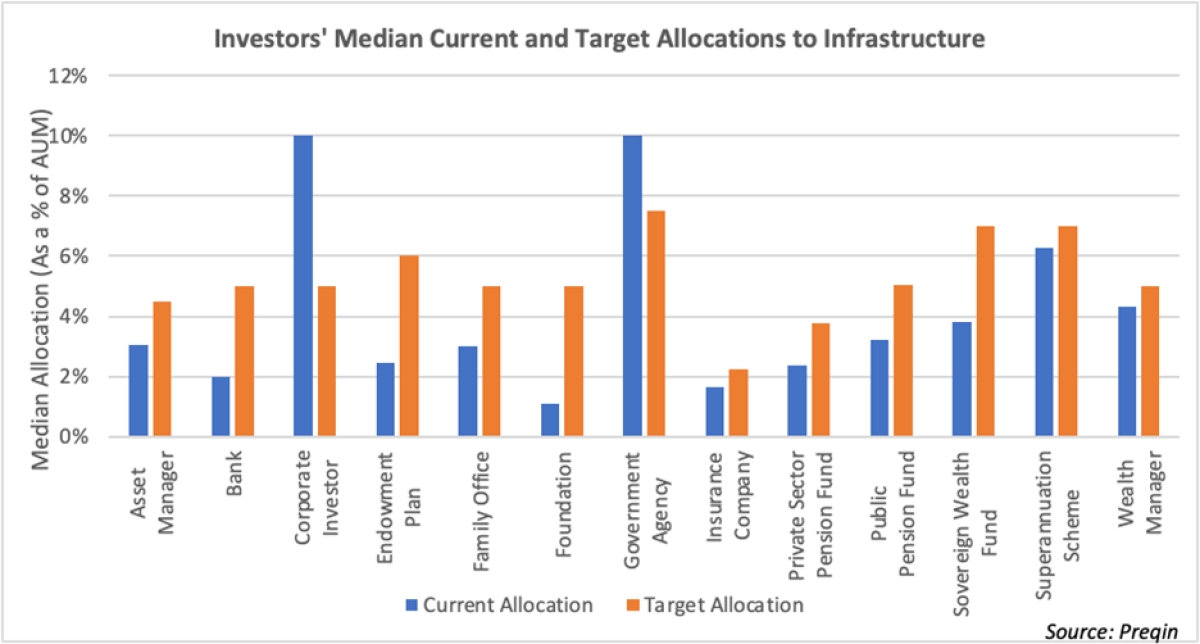

Exhibit 6: Investors’ Median Current and Target Allocations to Infrastructure

Source: Preqin

Exhibit 6 shows that, for the most part, asset owners are underallocated to infrastructure. However, many have a desire to increase their allocations, driven by the need for better diversification, inflation protection, and reliable income streams. Some of the largest investors, such as sovereign wealth funds, government agencies, and public pensions, have the most ambitious target allocations. We expect these target allocations to increase over time as inflation remains elevated and fixed income is no longer able to deliver current income.

Hedge Funds: The Data Is in the Details

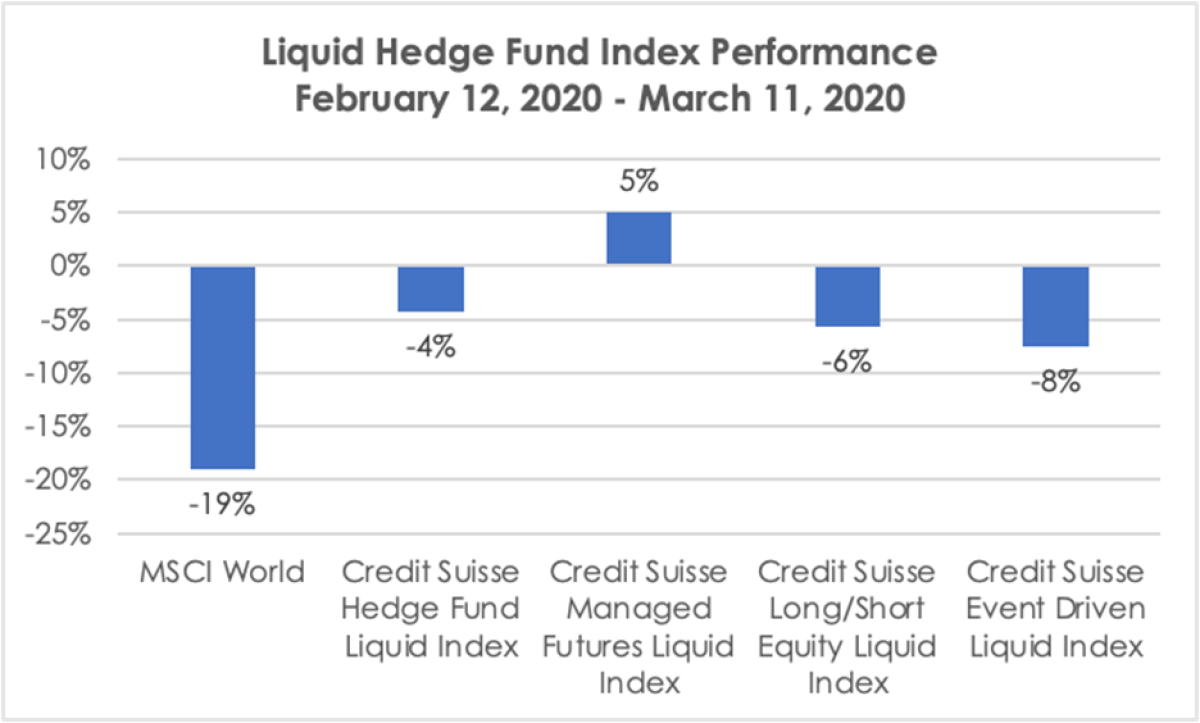

The requisite skill to generate alpha has always been a difficult task for most investment professionals. As both information availability and competition within public markets have increased, hedge fund managers continue to find ways to differentiate themselves. In The Next Decade, we claimed that hedge funds would need to prove their worth by providing downside protection during a difficult market environment. Fast-forward to March 2020, and the average hedge fund finally provided the downside protection they promised for years.

Exhibit 7: Hedge Fund Performance During COVID-19 Drawdown

Source: Bloomberg, CAIA Association

Note: Hedge fund performance is measured using the Credit Suisse Liquid Hedge Fund Indexes. Performance is from February 12 – March 11, 2020

Still, the competition remains fierce, and hedge fund managers have made other attempts to differentiate themselves in a competitive market. The size of the global datasphere has exploded, to the point where more than 50 zetabytes[9] is available for consumption. The wide availability of financial information and structured data means that managers have had to become creative to generate differentiated insights. According to AIMA, 67% of hedge fund managers are either users or currently trialing alternative data sources.[10] According to Preqin, nearly one-quarter of hedge fund managers utilize some form of artificial intelligence, relative to 1% in 2010, in their investment process.[11]

A Spotlight on Liquidity: Blurring the Lines, Ignoring the Vehicles

General partners (GPs) across any of the strategies previously mentioned are pushing against the artificial boundaries of public and private markets, no longer constraining themselves by investment vehicle. The announcement of the Sequoia Fund[12] in 2021 shows that venture capital managers are willing to break the cycle of only holding portfolio companies until they go public, extending the VC-fund life cycle into perpetuity. On the other end of the life cycle, hedge fund managers participated in 753 private deals, worth an aggregate $96 billion, in 2020—both measures of which represent new records.

Liquidity is no longer considered a benefit or drawback, but merely a feature. The blurring of private and public capital is an important trend that we believe will continue for years to come.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to read CAIA Association’s new report, The Portfolio of the Future.

[1] Global Asset Management 2020: Protect, Adapt, and Innovate. Boston Consulting Group. Found at https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/global-asset-management-protect-a…

[2] “Going Private: Hedge Funds and the Convergence of Private and Public Equity Investments.” September 2021. Goldman Sachs

[3] Pitchbook Analyst Note: SPAC Market Update Q1 2021

[4] JPMorgan Guide to Alternatives Q3 2021

[5] S&P LCD

[6] Real Estate Market Size Report 20/21. MSCI. https://www.msci.com/research/2021-market-size-report

[7] Global Infrastructure Outlook. Oxford Economics. https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/recent-releases/Global-Infrastructure-O…

[8] Aleksandar Andonov, Roman Kräussl, Joshua Rauh, Institutional Investors and Infrastructure Investing, The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 34, Issue 8, August 2021, Pages 3880 - 3934, https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhab048

[9] AIMA and IDC. Estimated figures.

[10] “Casting the Net – How Hedge Funds are Using Alternative Data.” AIMA. 2020.

[11] 2020 Preqin Global Hedge Fund Report

[12] The Sequoia Fund: Patient Capital for Building Enduring Companies. Found at https://medium.com/sequoia-capital/the-sequoia-fund-patient-capital-for…

About the Author:

As Managing Director, Aaron Filbeck oversees content and product strategy for the Fundamentals of Alternative Investments (FAI) Certificate Program. Prior to this, Aaron was responsible for the strategic direction of CAIA Association's content agenda, thought leadership, and member education initiatives, and supported content development for the CAIA Charter Program. His work has been published by Oxford University Press and The Journal of Investing, and covers topics such as ESG/sustainable investing, liquid alternatives, commodities, and asset pricing/factor investing. He is a frequent writer and speaker on these topics. Aaron’s practitioner experience lies in private wealth management, where he served as portfolio manager, overseeing asset allocation, portfolio construction, and manager research efforts for high-net-worth individuals and institutional retirement plans.

He earned a B.S. with distinction in Finance and a Master of Finance from Penn State University. He holds the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA), Certificate in Investment Performance Measurement (CIPM), Financial Data Professional (FDP) designations, as well as CFA Institute's Certificate in ESG Investing. He is a Past President of CFA Society Columbus and serves on the CFA Society Philadelphia Programs Committee. Aaron is an adjunct professor and serves on multiple advisory boards for Penn State University.