By Jamie Catherwood, an Associate at O'Shaughnessy Asset Management, and Founder of Investor Amnesia.

Who Cares About History?

I have been fascinated by history for my entire life. When I was younger, I loved learning about knights, hearing my grandmother’s stories about fleeing from London to the British countryside during World War II as German bombs rained down on London, etc. Despite the many warnings from my friends and puzzled looks from other parents, the decision to major in History for my undergraduate degree at King’s College London was a fairly obvious one from my view.

However, there are many people who think that history is simply a collection of names and dates, like a ledger book simply recording things that have happened before this current moment. I tend to think that the people holding this opinion are often those that had terrible history teachers in high school (or high school equivalent). There are some history teachers the present the subject in boring manner that truly does feel like a simple collection of names and dates. The best teachers, however, do the field of history justice by making stories come alive. I mean, history is just that, a collection of stories.

For example, I love this fascinating story about the origins of Columbia Pictures, and how they benefitted from the 1929 crash and ensuing depression:

In 1933, the Indianapolis Times did a fascinating six-part series on businessmen that made fortunes during the Great Depression. This article serves as a timely reminder that disciplined businesswomen and businessmen (as well as investors) can find good opportunities in dark times. This article focuses on the story of Columbia Pictures. You know, the movie studio / production company that you always see at the beginning of popular movies?

Well, this piece describes how the two brothers running Columbia Pictures, Harry & Jack Cohn, were able to take advantage of their disciplined and budgeted approach during the Great Depression as other studios that had spent recklessly went into bankruptcy.

‘During the last two years when many moving picture firms have been going into receivership or otherwise suffering financial pangs, a small outfit, Columbia Pictures. steadily has been growing and strengthening its position. The result is that its ratio of current assets to liabilities is 3 to 1.’

Read the whole article (it’s short), but the Cohn brothers learned their lesson in being disciplined with spending after their movie ‘Traffic in Souls’ made an enormous profit:

‘But to the Cohns, Harry and Jack… “Traffic in Souls” spoke another message in terms of the balance sheet. It cost $5,700, as Jack Cohn woll knew from having helped produce it, and its gross earnings were $450,000.

“Therefore,” reasoned the brothers Cohn, “it isn’t necessary to shoot the works like a drunken sailor to earn money on a picture.” That idea steadied them through all the years in which they saw film giants waging a battle of bankrolls around them. One depression fortune has been built in the movies apparently, and it belongs to the Cohns of Columbia Pictures.

As the larger companies have gone into receivership or suffered reorganizations and accumulated headaches. Columbia has enjoyed the best business in its history. It is earning more and has more to spend than ever before. During the bank holiday in March, most of the Hollywood studios also took a holiday; virtually most all of them cut salaries in half.’

This is an incredible story of good business management. The fact that Columbia Pictures remains a dominant player in the industry almost 100 years later is a testament to their approach.

I hope to persuade you in this brief post that history is an invaluable tool for navigating the present and future. And not only that it is a useful tool, but that history more broadly is a fascinating subject.

What History Is and Is Not

When describing why history is such an important tool at investor’s disposal, I often use an analogy that compares GPS systems to compasses. History is not a GPS system or roadmap. Just by reading historical sources, one does not suddenly obtain some crystal ball into the future with perfectly laid out routes for navigating the future (like a GPS system). History never repeats itself exactly, but there are certainly broader trends and patterns that repeatedly present themselves to those looking.

That said, I like to think of history as a compass for steering investors in the right direction when historical trends appear. By recognizing the patterns that repeat over the course of centuries we can better position ourselves for whatever lies ahead. For example, across hundreds of years there is a clear link between low interest rate environments and speculative booms. Whether it be during the tech bubble of the 1690s, London’s speculative boom in the 1820s, or the British bicycle boom in the 1890s, this pattern has held true for centuries.

In the last couple months we had a fascinating parallel to the events of 100+ years ago when the Russian government defaulted on its debt. In September of last year I launched a course on the financial history of Empires, and two of the lectures covered how the Bolshevik regime similarly defaulted on its debt in 1917.

Human Nature: A Sustainable Edge

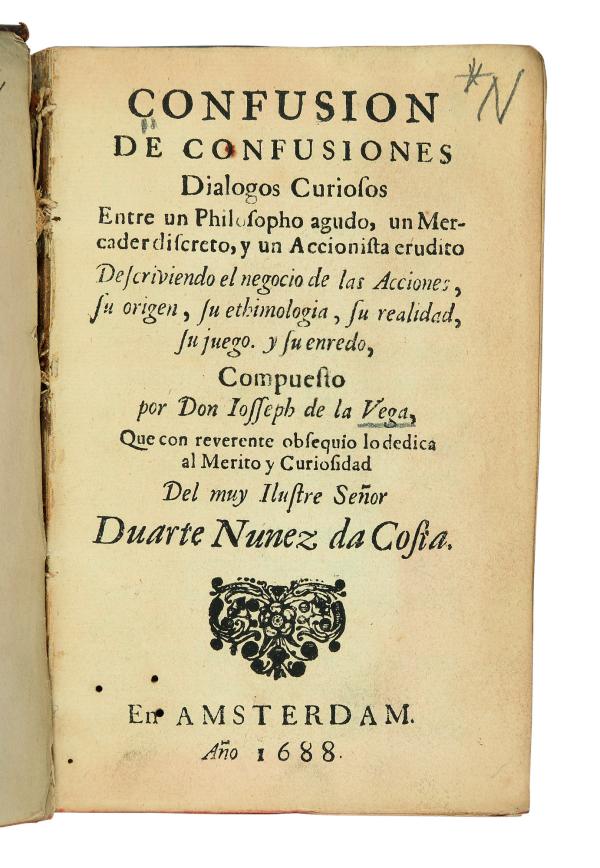

One of the other core lessons of all history is that one thing remains constant: human nature. Yes, technology and societies may get more sophisticated, but the individual people and their behaviors in each period are essentially the same as they were 400 years ago. Investors reacted to the volatile swings on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in 1688 the same way that investors react to market movements today. Just read this first behavioral finance book, published in 1688: Confusions de Confusiones

For example, the stories below demonstrate how investors fell for the exact same trick in the 17th and 19th centuries…

On the 17th century Dutch stock exchange, a small group of speculators realized how easily influenced their peers were by individual trader’s decisions, and the short-term news cycle. Manipulating the market, therefore, was as simple as providing traders with the ‘hot tip’ that they scoured the exchange for each day.

An effective system was quickly developed in which the savvy speculators accidentally dropped notes around the exchange that held misleading stock tips:

“If it is of importance to spread a piece of news which has been invented by the speculators themselves, they have a letter written and [arrange to have] the letter dropped as if by chance at the right spot. The finder believes himself to possess a treasure, whereas he has really received a letter of Uriah which will lead him into ruin.” — Joseph de la Vega (1688)

Their victims, the unsuspecting traders, eagerly snatched the fallen notes and traded on the nefarious tips. Predictably, the trades were beneficial to the authors of these notes, as they often encouraged traders to bid up the prices of shares that the speculators owned.

The success of this trick is a testament to many investors lack of independent analysis, and due diligence. Dutch traders seldom questioned the quality of companies referenced in these notes, and purchased their shares solely because of another investor’s intent to do the same. ‘There has to be a reason he’s making this large purchase. He must know something!’

Two hundred years later, investors were still falling prey to the very same trick. Daniel ‘Uncle’ Drew, the notorious 19th century speculator, implemented a variation of the Dutch system using his handkerchief:

“In order to get the price of the stock as high as possible before beginning to sell it short, he [Drew] visited a NYC club where stock traders congregated. Sitting down on a particularly hot day, he pulled a handkerchief out of his pocket to mop his brow. As he did so, a small piece of paper fell onto the floor… After he left, the other traders pounced on the paper, which just happened to contain a ‘bullish’ piece of news on the Erie. They then proceeded to frantically buy the stock”

Applying Historical Frameworks

Outside anecdotes of human behavior, one of my favorite practical applications of financial history for investors is The Bubble Triangle, a framework that historians John Turner and William Quinn from Queens University Belfast put together. In this clip below Professor John Turner walks through the Bubble Triangle.

Marc Andreessen on the Value of History

If you still don’t feel there is any merit to studying history, perhaps the value of history is best explained by legendary venture capitalist Marc Andreessen in this clip below:

Niall Ferguson on the Wrong Lessons from History

As mentioned, there are also bad applications of history. Arguably no person is more synonymous with the field of financial and economic history than Niall Ferguson. Author of The Ascent of Money, and more than a dozen other brilliant historical works, I asked Niall in my last course about what he feels are the wrong lessons economists and policy makers take from history.

Original Article: Why History Matters — Investor Amnesia

About the Author:

Jamie Catherwood is an Associate at O'Shaughnessy Asset Management, and Founder of Investor Amnesia.

He publishes a weekly financial history newsletter to +14,000 subscribers and offers courses on the history of markets. His work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Bloomberg, New York Magazine and more. Jamie has given presentations and talks on financial history at Yale University’s School of Management, BloombergTV, and industry conferences across the country.