By Carlin Calcaterra

In the intricate web of finance and investment, various vehicles are employed to generate returns and manage wealth. One such vehicle, which has gained traction over recent decades, is the search fund. A search fund is a unique investment vehicle, typically established by one or two entrepreneurs, aimed at acquiring and operating a single privately held business. Over the years, search funds have grown in popularity and have seen increasing success in various markets.

CAIA recently hosted a webinar on the topic. This post serves to summarize that discussion, delving into the nuances of search funds, exploring their structure, purpose, and the key distinctions that set them apart from traditional investment funds.

What is a Search Fund?

The concept was pioneered in the 1980s at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This investment model has become a popular path for aspiring entrepreneurs who want to acquire and operate a single privately held business but may not have the capital required for direct acquisition.

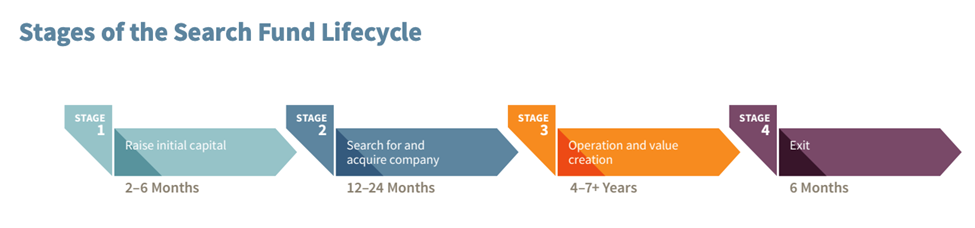

A search fund involves one or two entrepreneurs who raise funds from investors, some of whom become mentors. They use these funds to find, acquire, and manage a private company for six to ten years. This process can lead to quick ownership, good financial returns for both parties, and successful businesses. The stages include fundraising, searching and acquisition, operation, and eventually selling or providing liquidity.

Search Fund Lifecycle

Search funds are usually structured as limited liability companies. In a search fund, the money is raised in two stages:

The Search Phase: The entrepreneur(s) raise capital from investors to cover the costs associated with identifying and evaluating potential acquisition targets. This phase usually lasts between 18 to 24 months. The funds raised are used for salaries, travel, due diligence, and other related expenses. Investors in this phase bet on the entrepreneur's ability to find a suitable business to acquire.

The Acquisition Phase: Once a target business is identified, additional capital is raised to finance the acquisition. This phase can also include post-acquisition support where the entrepreneur takes on a managerial role, often becoming the CEO, to drive the growth and profitability of the acquired company. Investors from the search phase typically participate in this round, along with new investors who are brought in to provide the necessary acquisition capital.

How Does a Search Fund Differ from a Traditional Commingled Investment Fund?

Understanding the key differences between search funds and traditional commingled investment funds is crucial for investors and entrepreneurs alike. Here are some of the primary distinctions:

Purpose and Structure

The primary objective of a search fund is to acquire and operate a single business. The structure is typically lean, with one or two individuals (the searchers) raising initial capital to support the search process and later raising more substantial funds to complete the acquisition.

A traditional commingled fund, on the other hand, pools capital from multiple investors to invest in a diversified portfolio of assets. These funds are managed by professional fund managers who make investment decisions on behalf of the investors. The structure is more complex and involves a larger team of analysts and managers.

Investment Focus

While the idea of acquiring and growing midsize businesses is not unique to the search fund construct, its scope does make it unique. In a search fund, the focus is on acquiring a single, privately held company that the searcher can manage and grow. The investments are typically in small to medium-sized enterprises with stable cash flows and growth potential.

Here, the comparison to “traditional” funds becomes a bit funny. At the end of the day, search funds are an investment in the equity of private companies. This is no different than a “traditional” private equity investment. However, the more collective investor owner/operator model of the search fund differs from that of the GP/LP structure in traditional private equity commingled vehicles.

Risk and Return Profile

Investing in a search fund involves higher risk due to the concentrated nature of the investment and the reliance on the searcher's ability to identify and successfully acquire a target company. However, the potential returns can be substantial if the acquired business performs well.

Traditional funds are generally considered lower risk due to their diversified nature. The returns are typically more predictable and stable, though they may not be as high as the potential returns from a successful search fund acquisition.

It should be mentioned, however, that both traditional private equity and search funds may provide superior risk/return profiles than that of public equity.

Investor Involvement

As alluded to earlier, investors in a search fund often play an active role, providing mentorship, guidance, and support to the searcher. They are typically experienced entrepreneurs or investors who can add value beyond just capital.

Investors in traditional funds are usually passive, relying on the expertise of the fund managers to make investment decisions. Their involvement is limited to regular updates and performance reports from the fund managers.

Conclusion

In summary, search funds offer a unique opportunity for entrepreneurs to acquire and manage a business with the support of experienced investors. They differ from traditional commingled investment funds in terms of purpose, structure, investment focus, risk and return profile, and investor involvement.

Search funds provide a pathway for entrepreneurial-minded individuals to step into leadership roles and create value through hands-on management, while traditional commingled investment funds offer a more diversified and passive approach to wealth management. Both have their merits, and the choice between them depends on the specific objectives and preferences of the investors and entrepreneurs involved.

About the Contributor

Carlin is an accomplished investment strategist, practitioner, educator, and author. With over 15 years industry experience, she is a subject matter expert on strategic asset allocation, with a focus on private markets. She served as a discretionary institutional asset allocator at Goldman Sachs and Mercer. Most recently, she led a wealth management solutions team at Ares Management, championing private market education and thought leadership for financial advisors. Her published works range from 101 level education to risk-based optimization strategies and seek to bring together asset class insights, macro considerations, and portfolio strategy. She holds a BA in Economics and French from Bucknell University and expects to earn the CQF designation in June.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/