A recent paper by S.P. Kothari, Deputy Dean of the Sloan School of Management, M.I.T., and two associates, sends us forward to the past, recalling the early days of modern portfolio theory as formulated by Harry Markowitz in 1952.

A recent paper by S.P. Kothari, Deputy Dean of the Sloan School of Management, M.I.T., and two associates, sends us forward to the past, recalling the early days of modern portfolio theory as formulated by Harry Markowitz in 1952.

Specifically, the paper, “Generating Superior Performance in Private Equity,” applies the principles of MPT to the question of the performance of private equity funds.

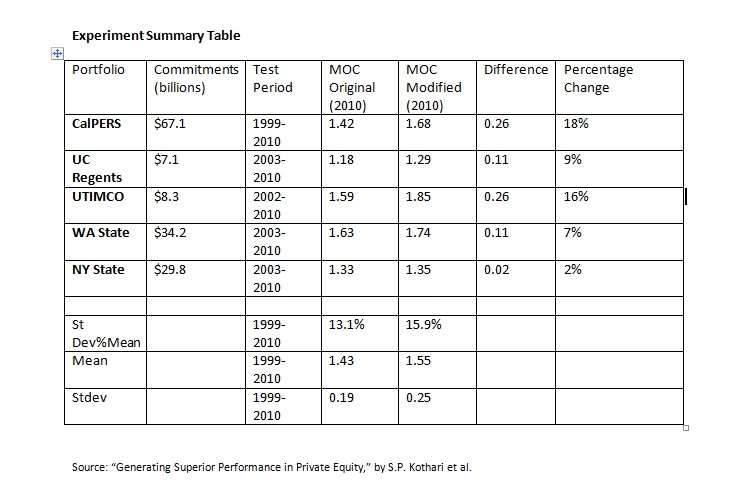

Kothari, along with Gitanjali Swamy and Konstantin Danilov, studied the private equity portfolio selection decisions of five sophisticated institutional investors through a recent period of seven to 10 years. They asked whether, given these portfolios, it is possible to employ the basics of MPT to create a “more efficiently allocated subset that yields a superior return-to-risk trade-off as compared to the original portfolio?”

[Swamy is the president of Massachusetts-based consultancy AARM Corp. Danilov is affiliated with HEC Paris.]

Five Portfolios

The institutions whose portfolios were part of this test were: CalPERS, the University of California Regents, the University of Texas Investment Management Co. (UTIMCO), the Washington State Investment Board, and the New York State Common Fund.

The columns headed MOC in that table provide us with the “multiple of capital” metric used by these authors as their overall measure of investment return. They contend, in accord with the AARM-Insight framework, that MOC is preferable in dealing with the PE world to the use of other measures such as internal rate of return (IRR), because it is “less subject to accounting manipulation that could distort the true performance.”

The paper incorporates a critique of much existing research on the PE industry. Kothari et al. believe that there has been an unfounded emphasis on manager selection, as distinct from strategy selection and vintage. Relatedly, there has been an emphasis on the persistence of performance by top quartile GPs, “access to whom” as they observe “is often based on exclusive relationships.”

As a consequence of this focus, there has been little research on such matters as whether the risk-reward efficiency frontier applies in the PE world. That is the gap Kothari et al hoped to fill.

Conclusion

Their analysis might be accused of hindsight bias. They maintain that certain modifications in the portfolios of these five investors, modifications suggested by the basic Markowitz-derived notions of diversification and a risk-return frontier, would in fact have increased the MOC of each of these portfolios as of 2010, and would have raised the MOC of two of them (CalPERS and UTIMCO) to a remarkable extent.

They employ a “subtractive” method, in part in the expectation of eliminating their own hindsight. Their model drops from each portfolio those new investments that, at the time the investment decisions were made, did not move the portfolio closer to the risk-return frontier, as understood by the ARRM algorithm.

“In essence, any new investment that creates ‘redundant exposure’ which does not increase diversification (thus reducing risk) or increase expected return (while maintaining the level of risk) is eliminated,” they write, “thus creating a more optimal ‘Modified’ portfolio.”

They acknowledge their approach is a bit “naïve,” and hope that analogous analyses will be run by later researchers that will create a more “robust framework for PE portfolio construction.” But for now, it appears, their conclusion is that institutions investing in PE funds should learn from Markowitz’s original insight and increase their diversification.