A new working paper from the International Monetary Fund engages with some of the fundamental issues with Japan’s economy. It is bound to be of interest to those who are fishing for alpha in those waters.

A new working paper from the International Monetary Fund engages with some of the fundamental issues with Japan’s economy. It is bound to be of interest to those who are fishing for alpha in those waters.

These days the headline news about Japan involves the fear of Sino-Japanese contagion. What ails the dragon next door, ails Japan. A fall in Japanese factory output, thus, is easily attributed to a slowdown in China, and to real or anticipated decline in China’s demand for what Japan can make. That isn’t what the IMF report is about.

Going Deeper

But Japan’s troubles require deeper consideration than that. After all, what do we even mean when we speak of what Japan “makes” for sale in China or elsewhere? Are we speaking of objects manufactured in Japan, or objects manufactured elsewhere in the world, perhaps in the United States, by Japanese companies, or of both? And from a macro-economic point of view, does it matter?

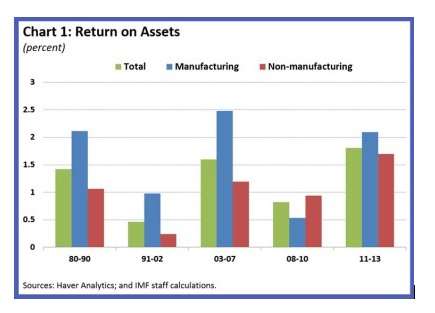

One point the IMF paper makes, as reflected in the chart reproduced below, is that manufacturing no longer plays the leading role in Japan that it once did. In previous boom periods (the 1980s as a whole, in the early 1990s, and in the period that corresponds with the US. centered housing derivatives bubble), manufacturing, as reflected in the blue bar in each cluster below, clearly stood out in its return on assets, head-on-shoulders above the RoA for the rest of the economy.

But in the final years of the first decade of this century, manufacturing (the blue bar in the fourth cluster) lagged. In the most recent or fifth cluster, its RoA is again above that of other sectors, but it is no longer markedly so.

The IMF draws lines between the dots: Japan is outsourcing its manufacturing. This is true both macro and micro: individual manufacturing firms headquartered in japan are sending the production work overseas even when it remains within the same corporate structure. Mother Nature has lent a hand in her own fashion to this trend, which accelerated after a 2011 tsunami rendered power supplies uncertain.

Deleveraging is Good. But … how good?

The report, prepared by Joong Shik Kang and Shi Piao, also discusses deleveraging. Japanese firms have been paying against their debt for a quarter century now. Over that period the leverage ratio has decreased by more than 10% both inside and outside of the manufacturing sector. That’s a good thing. Firms have at present a much lower debt payment burden than they otherwise would, and liquidity conditions have improved.

But this good news itself has a worrying side. For given these facts, there should be a boom in reinvestment in manufacturing assets. That much more does it surprise, then, that “the recovery in corporate investment remains subdued across all sizes of firms” nonetheless, particularly for the larger firms. In an abstract of the paper posted at the IMF’s blog, this is called the “riddle of sluggish investment.”

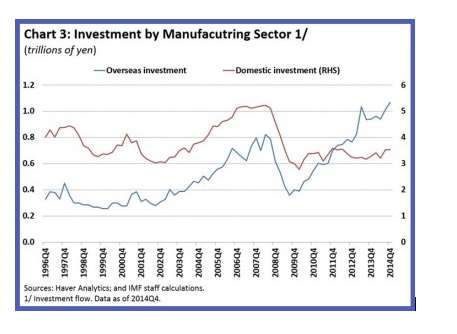

[The numbers along the y axis of the chart above, on the left, indicate the amount of overseas investment in trillions of yen: that is, they correspond to the blue line. The numbers on the other y axis, on the right, indicate the amount of domestic investment, corresponding to the rust-colored line.] When investment is broken down in this way into the overseas and domestic sectors, a sharp and recent change becomes obvious.

Solving the Riddle

Overseas investment in this sector, now above 1 trillion yen, amounts to one-third of domestic investment, or one-quarter of the total. Domestic investment on the other hand has never recovered from the 2008 drop-off (and that drop off itself was the last moment when those two lines moved in parallel).

This is unfortunate, because the domestic manufacturing scene could make use of fresh investment. In its absence, Japanese domestic production capacity has declined by about 4% since 2011.

The critical issue here, for the IMF, is whether firms that keep their manufacturing operations offshore act differently than do firms that keep their manufacturing at home. Will the trend toward outsourcing have macroeconomic consequences? These authors’ answer, in short: Yes. There is a difference. Companies dependent on their overseas operations bear more risks due to financial intermediaries. Bearing these risks, they are more dependent upon internal financing than are their domestically-oriented counterparts. Given the internal nature of their financing, in turn, their decision making, especially on the expansion side of the business cycle, is slower.

Thus, the outsourcing trend is a weight upon the economy, counter-acting the positive factors that might otherwise have produced a more robust recovery than is now in evidence.